First Pressing was a project that featured around 40 Meanjin/Brisbane-based tattoo artists, drawing attention to the skill set of a group that is often overlooked in arts circles, despite the booming popularity of tattoos in the West, and the deep-rooted international history of the practice. Tattoo artistry has held a strong social significance for generations and, over time, has spurred political movements and advocated for change.

Curated and developed by local artist couple Sam and Beck Irvine, First Pressing encouraged alternative artists, including tattooists and illustrators, to produce 12-inch by 12-inch artworks emulating the style of vinyl record sleeves. In part, the goal was to encourage connections and solidarity between musicians and visual artists—especially important in the current political climate. So, fostered by the community, 100 or so visual artists, musicians, tattooists, curators, writers and art appreciators crowded into The Station, a small brick building tucked into a corner of Fortitude Valley.

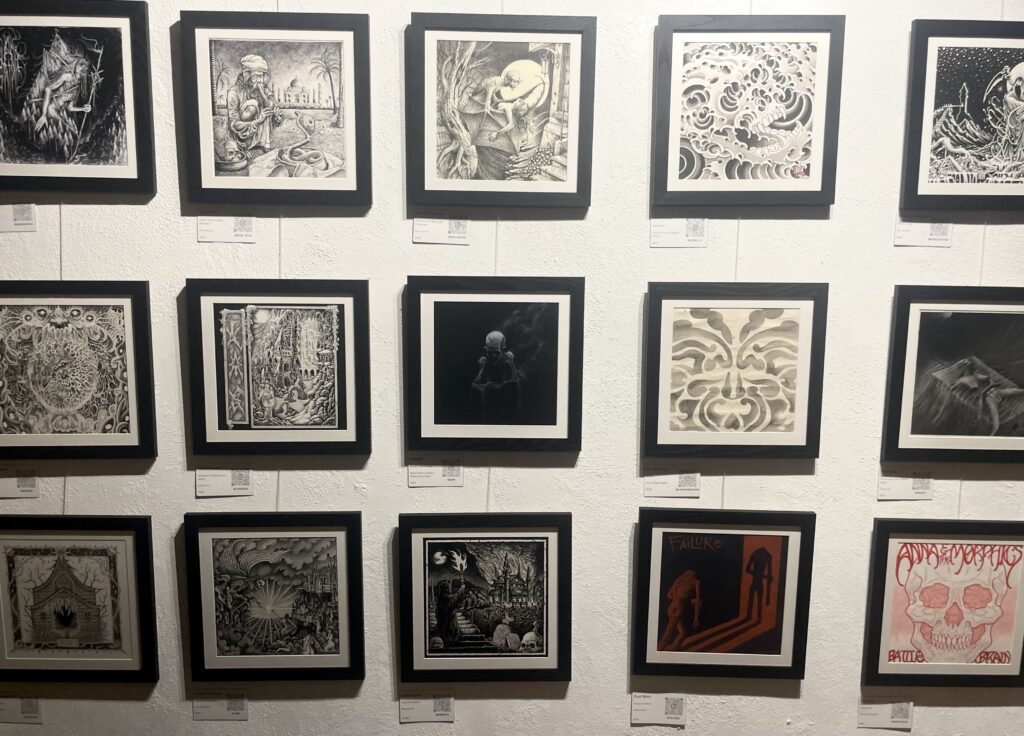

Alternative art forms are fuelled by communities, and this event was no exception. Upon arrival I was greeted with crowds of people sharing stories, the strong scent of craft beer intermingled with cheap cigarettes, and a sense of home. Coming from a background in the Meanjin hospitality and music industry, there was a familiar nostalgic feeling about this DIY space. The artworks covered two walls, each featuring a collection of original square works on paper framed in uniform black wood. The pieces were arranged in three columns with approximately six works in each, emulating a traditional salon hang.

The space was welcoming and the event hosts facilitated the sale of work to ensure all their artists felt supported. Though this did not prevent them from taking time to speak to me passionately about each artist and the inspiration behind this curatorial project, explaining the importance of tattoo as a cultural medium, and the legitimacy of its position within art history.

Salon hangs were, and remain, the easiest way to display a large collection of framed artworks, originating in the 1600s from the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris, where artists would jostle for the best possible position. Although less common in large exhibitions today, the hanging style harkens back to the days when working artists would get together to display, and gain further recognition for, their work. It also allows for multiple styles to be displayed alongside each other in a small gallery without thematic constraints.

A detail that is often neglected when talking about tattoo artistry is the profound history and development of different styles—which are often distinct from familiar styles in other forms of visual art. For instance, upon viewing this display, I was able to pick out American and Japanese Traditional styles, known for their vibrant block colouring. But it was also clear that subversive techniques are being applied to these established forms, taking them in new and innovative directions.

For instance, Sam Hillcoat’s The Infamous Mobb Deep displayed the typical shapes and styles of American tattoo art but, in a break with tradition, contrasted greys and yellows rather than purely primary colours. Hillcoat’s harsh colour blocks also showcased a unique style that is not often seen in the watercolour media he employed—a medium that in itself acts as a subversion of tattoo. His solid blocks of colour were abruptly broken up by stippling to emulate patterns of blood spray, a technique unique to the genre.

This combination of mediums is a good reminder that many tattooists begin their careers with a traditional artistic foundation before moving into alternative practice. Many of the artists demonstrated an extensive understanding of art history, as well as the history around their chosen career path. One example is Ben Hale’s untitled design inspired by Shane MacGowan’s music. The red haze in the background of his piece recalls the work of Francisco Goya, while the strange figures in the foreground are like those of Paul Gauguin. Both artists depict experiences of culture through an individual lens, which is exactly what Hale has aimed to translate. Hale described the impact of MacGowan’s music on the work: “Like all good art, [it] has always inspired me with stories of the universal nature we experience … uniquely individual but endlessly common.”

The left-hand side of the room exploded with detail, showcasing artists working with single or dual-toned colour palettes. With limited colour options, artists use bold lines and shading to create depth in their work. Aureole’s design uses pink and red skulls for an album cover for femme punk band Anna and the Morphics, a group whose music tackles the experience of trans people and women in Australia. The artwork follows the band’s gothic and dark-wave routes by featuring demonic caricatures of its members. The use of pink in a genre full of black and red added a feminine touch to the show, while maintaining the fierceness of punk culture. As the industries of ink and sound remain male-dominated, this piece stood out as a form of defiance and recalled the spirit of artworks by 17th-century Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi, one of the first to unabashedly show feminine rage and dominance in her paintings.

This aggression was echoed in Jayla Lawrence’s work, whose impressive stippling and blackout techniques are crucial to creating depth on the skin. Borrowing from medieval aesthetics, Lawrence’s Return Home subverted elements often found in medieval prints, with gothic skulls, snails and worms depicted within the constraints of a boned barricade. On close inspection, it was apparent the detailing of the wood grain and the bodies of these creatures required a variety of sketching skills and fine details. These animal motifs were also contrasted with blacked-out windows and silhouetted branches.

First Pressing has given me, as someone who has always had a passion for alternative art forms, a new-found appreciation for the history and culture of tattoo. Those who work in the tattoo industry not only have an understanding of traditional fine arts, but also of the history of their medium and its social context. It takes true commitment to place something on the body forever and it is no surprise that these artists—and they are artists—have dedicated countless hours to their craft while developing innovative artistic styles. Events such as these are crucial to fostering support for alternative artists and allow tattoo artists to share their work in a formal, yet still accessible, setting. First Pressing may be one of the first shows of its kind in Meanjin, but surely it won’t be the last.

Cassius Owczarek is an artist, curator and writer studying at the University of Queensland who is living and working in Meanjin/Brisbane.