Primavera is an annual exhibition coordinated by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney. Each year artists under 35 are invited by a guest curator to present new bodies of work. The intention of the exhibition is to highlight young Australian artists, giving them a national platform to share their practices. Primavera is a staple of the MCA exhibition calendar and a jumping point for early career artists to gain national attention. Talia Smith was the guest curator for Primavera 2023 and the invited artists were Tiyan Baker, Christopher Bassi, Moorina Bonini, Nikki Lam, Sarah Poulgrain, and Truc Truong. In her curatorial essay, Smith shares how she has connected the artists’ practices through the themes of protest, reimagining, and perseverance.

Primavera at The Condensery in Toogoolawah is the initial stop on a national tour and marks the first time the exhibition has travelled beyond Sydney. On entering the exhibition, I wondered how these works would translate to different contexts. Would they still resonate with audiences once removed from the big city? This is the frame I took to the exhibition and through which I will explore the three works discussed below.

The first work I encountered was Tiyan Baker’s Personal computer: ramin ntaangan (2022–23), with its green and red glow beaming up the gallery walls. Baker’s work is a hybrid installation of typical computer components and personal artifacts: a monitor stands on a green spray-foam rock, a keyboard rests before it, a mouse and mousepad sit on a bamboo table, and an heirloom machete is embedded in a smaller green rock. To the right is a miniature baruk, an Indigenous Malaysian longhouse. A processing unit made by Baker sits within this structure alongside a small screen displaying a crocodile spinning on an invisible spit with a sword held in its jaws.

As the title suggests, Baker’s is very much a personal computer, she has constructed the processing unit and hand-thatched a baruk. In creating this work Baker connected with her heritage, using Malaysian Bidayuh techniques to thatch the roof of the baruk. The work also highlights another way that she connects to her heritage—through the internet. A computer now provides an avenue to communicate with family via WhatsApp and Facebook. Through this work, Baker’s shares a contemporary interpretation of diasporic experience. Connecting with her heritage can now be achieved with a strong internet connection irrespective of where she is located.

This work operates on another level when presented in regional locations where reliable internet connectivity is a relatively recent phenomenon. Having lived regionally for a number of years, I experienced an internet connection as a lifeline that enabled me to briefly leave the small town I was in and connect with peers. Many remote communities still do not have this access, which cuts them off not only from our nation’s capitals but also from communities beyond this country.

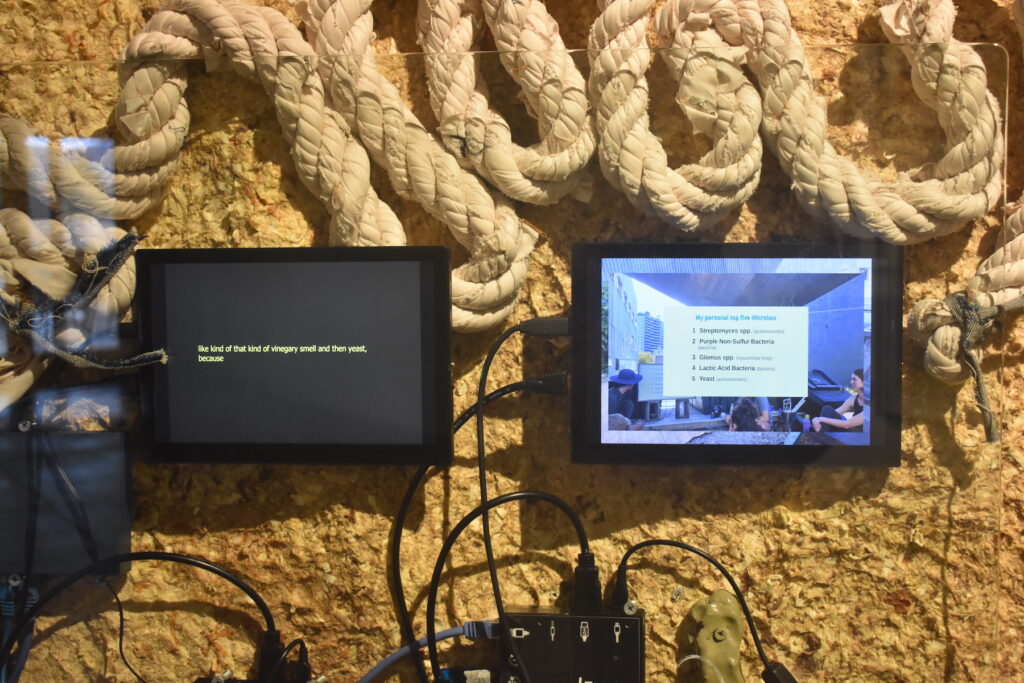

Behind Baker’s work is Sarah Poulgrain’s Learning how to build a houseboat: walls, fixings and rope (2023). This is a continuation of Poulgrain’s long-standing commitment to learning new skills and sharing them with others. In the face of declining housing affordability and the increasing likelihood of extreme weather events, both of which disproportionately affect the nation’s lowest income earners, Poulgrain wants to use their practice to empower communities to collectivise and share skills.

Learning how to build a houseboat: walls, fixings and rope consists of two parts: a coffee table with documentation laid across its surface and a welded frame with rough ‘walls’ of paper pulp. The frame is the beginning of the wall of a future houseboat. On the back of the frame is a hand-made rope, a tangle of cords, and two screens. One is a video of one of Poulgrain’s skill-sharing workshop; the other is a transcript of the conversation that takes place. I learnt about the properties of different types of bacteria and mycelium and microbes, demonstrating the knowledge exchange process that takes place between workshop participants during construction.

After living through the devastating Meanjin, Brisbane floods of 2022, Poulgrain decided to learn the fundamentals of boat building with the end goal of constructing a houseboat: a structure that can withstand floods. As a fellow Meanjin resident, this work brings back memories of the disaster that took seven lives and left thousands of people displaced. Adding a local connection, Curator of The Condensery, Madeline Brewer, shares that the head of the Brisbane River, historically a contributor to floods, is located very near to the site of the gallery. The Somerset region was also significantly affected by the 2022 floods, with people cut off from access roads and electricity for days and livelihoods greatly impacted. Poulgrain’s work raises the question: would collective action have assisted in preparations or helped to reduce the flood’s devastating impact?

Scattered throughout the exhibition are Marina Bonini’s dapalama (between) (2023). This series of works are simple vinyls of black text provocations. The first, between Truc Tuong and Baker’s installations, reads:

Bamunga

Feel (to)

With my hands

Mirramna

Look (to)

With my eyes

Bunyma

Make (to)

With my bawu (body)

Angurrma

Be (to)

A winyarr (Aboriginal woman)

The text gently prompts me to reconsider how I experience the works before me. Bonini particularly foregrounds the bodily experience of art-making/viewing: feeling with our hands, looking with our eyes, and making with our bodies.

To the left of Sarah Poulgrain’s work another text incursion can be found.

The institution is a vessel

A transient empty

Structure

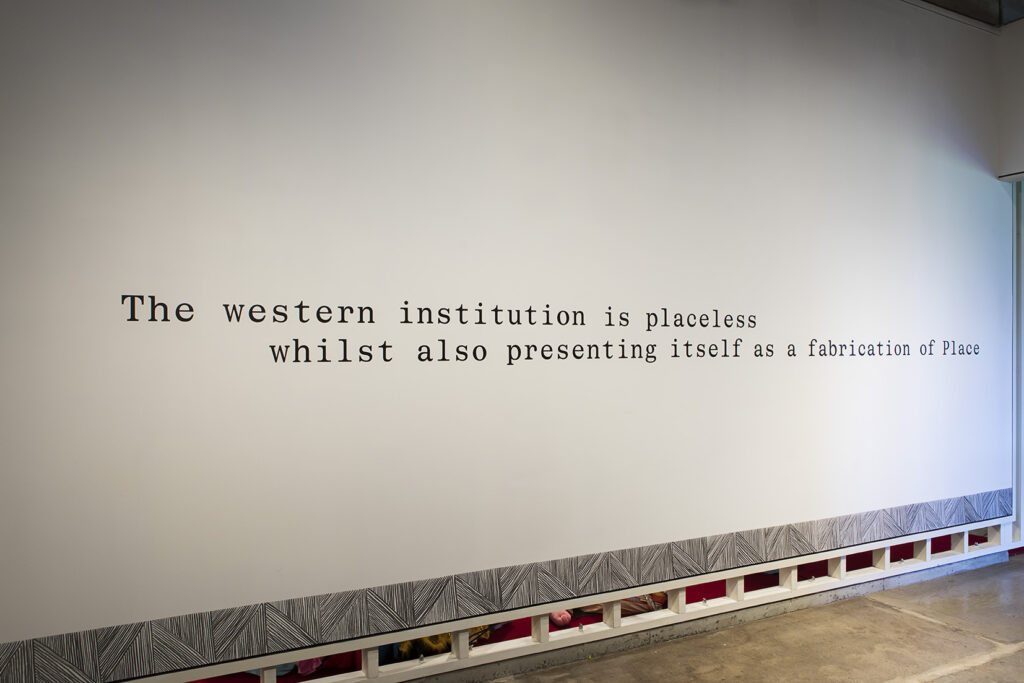

The final text piece is located in the second gallery space of The Condensery.

The western institution is placeless

whilst also presenting itself as a fabrication of Place

This work is positioned over a hand-drawn linear charcoal piece that lines the bottom of the wall.

Bonini views these pieces as ‘sites of resistance’ that work to recentre First Nations voices in the gallery. Through these works, Bonini prompts you to consider different ways of looking at and experiencing art beyond western institutional norms. Their positioning between works encourages visitors to consider the entire exhibition from this viewpoint and influences your readings of the other works. As the exhibition travels around Australia, these text works promise to serve as important reminders of the Country on which viewers’ stand, reminding us that we are always on Aboriginal land.

On first impression, Primavera feels compressed, with works hung closely to one another. It is impossible to consider these pieces individually; they are in constant communication with the artworks in their periphery. However on engaging with the works, particularly through Bonini’s additions, the conversations between them is a strength of the exhibition. The artworks in Primavera are rich in their own right, but when grouped together they form a powerful picture of the future of contemporary art in this country.

Hannah Williamson is a curator who lives and works in Meanjin/Brisbane.