The taste of a dying vape is sharp and metallic, a crackled mix of scorched cotton and singed copper wiring. The vapour has a dry, acrid edge, like you’re inhaling the last wheezing breaths of an exhausted battery. Burnt circuitry with a faint note of charred plastic, mingling with the thick saliva of your stale mouth. When I left Dithyramb, and as visual descriptions lagged behind, it was this particular sense of flavour that stayed with me as the most acute sensation of the exhibition.

Curated by Holly Eddington, Dithyramb is a visceral, biotech-fuelled exhibition, intent on reviving Dionysian ecstasy for the metamodern era. Hosted in the basement-level nightclub, Door84, the venue’s underground setting synced homogeneously with the dark, digital aesthetic of the nine artists showcased.

Visitors stepping off Burnett Lane passed through an inconspicuous grey door, followed the descending steps of a narrow hallway and dropped into the dead static charge of the nightclub. The nightclub-turn-gallery space is a long, rectangular room, its black walls and dance floor absorbing synthetic light. The air is thick with the antiseptic sting of freshly cleaned vodka soda spillage, a lingering trace of the club’s chaotic routine. Another scent loitered in the air, sweet and tangy, with a salty base note, an intimate musk that tugged at memories: half-remembered kisses in cramped stalls, skin and sweat.

I was surprised to discover the source of this smell. Jack Snow-Viener’s Instinct’s Pink (2024) represents an artistic exploration of scent, a medium often overlooked but powerfully engaging. Flanking other works in the exhibition were two inconspicuous aroma diffusers. They rasped a steady haze of smoke, administered with evocative perfumes, in what was called an ‘olfactory-scape,’ designed to ground the body and dislocate it. Once noticed, it was impossible to ignore.

While the scent enveloped the space, audio further intensified the sensory experience, stacking the ambience with sound, at once synthetic and uncomfortably organic. Gus Green’s Shorts, Slow + Reverb (2023) is disorderly layered noises sampled from the Youtube algorithm. The resulting music had a shimmery, choral texture that moved between disorienting, glitchy moments and a sort of cold liquidity. It submerged the room in an atmosphere that felt somehow like benedictine laments, but with a twisted, computerised pulse.

With Green’s music vibrating into the background, my attention fell to paintings positioned just beyond the shadows of the hallway entrance, acrylic on shaped particleboard, two resting on black-cushioned, metal barstools repurposed as plinths, two hung on metal barricade fences. They had the impression of low-poly digital renderings, pixelated, but affectingly and notably hand painted. Jent Do manipulates generative AI to synthesise bizarre, biomechanistic forms that serve as reference for their paintings.

Do’s paintings surrounded a large, violently tender and penetratingly sweet, airbrushed acrylic by Isabel Trufas. Play Piercing II (2023) may be confronting for some—with its close look at corset piercing, kink associations, and body-mod aesthetics—yet to me, the effect of this work on the room was soothing, a comforting reflection on the beauty and pain of self-creation.

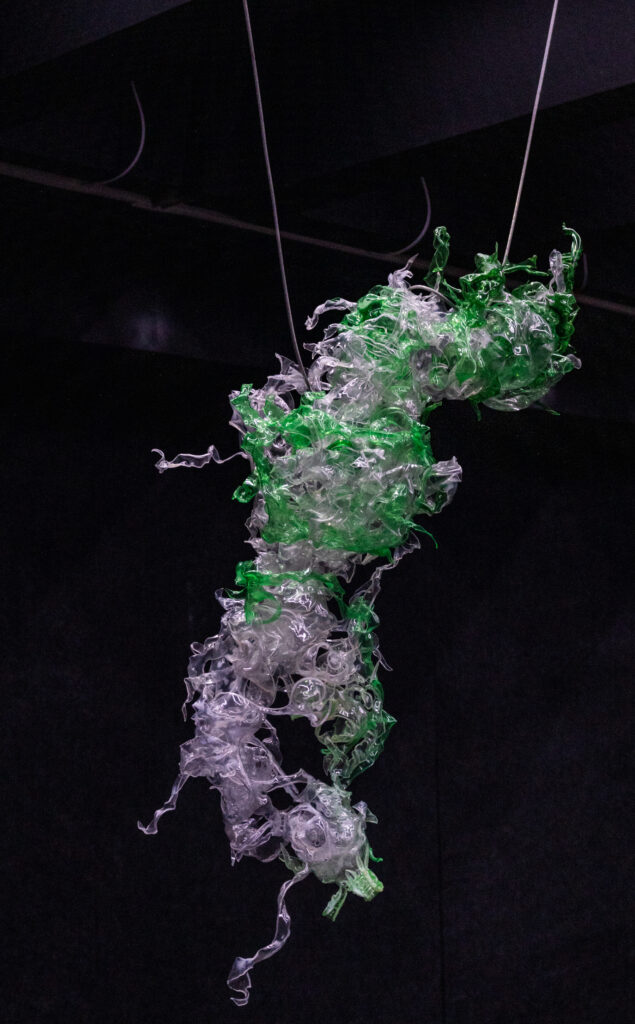

By one wall, sculptures hung from the ceiling in suspended, fluid motion. Melted plastic bottles were shaped into delicate, organic strands that resembled viscous droplets dispensed in water, each tendril holding the tension of weight and buoyancy. In this work, Gabrielle Lai pursued an affect they termed “neo-chiaroscuro,” revivifying the Baroque representation of harsh light and shadows in the play of club lighting. These works hung forward from an assemblage by Khôra Catenaro: a sculpture of the Virgin Mary submerged in red wine and bordered by mounds of salt. The mix of salt and found materials layered a sense of ephemerality over the dense, symbolic weight of religious iconography.

On the opposite wall, a series of thirteen photographic prints demanded attention. Their diminutive size compelled me to lean closer, as the gaze of the photographer, Catherine Paris Panagiotakopoulos, became my gaze. The images came into focus: scenes of BDSM; purple bruises; and raw, corporeal flesh.

Adjacent to Panagiotakopoulos’s work lay the vivisected remains of a laptop screen, its green circuit brain exposed, wires dangling like severed nerves. The scalped, illuminated screen flickered, strobing through digitally corrupted yet otherwise clinical montages of surgical scenes. This imagery escaped the cyborg body of the screen like memories slipping from grey matter in the midst of a botched craniotomy. The pathological dataset of this work bled into its partner piece, Daniel Doyle’s Support (2024), which projected a decontextualised panacea onto taut white fabric, with sterile haunting impact.

The final and largest artwork, elevated onto the stage typically reserved for DJs, was Noistruct’s vinyl prints on acrylic. Like something noclipped into the room from a cyberpunk RPG, this work was suspended from industrial chains and looked like dissected, virtual anatomy slides. At its centre, a flickering, glitch-ridden projection was corrupted, alive, ever shifting. The chromatic aberrations are a quality inextricably iterative from bits of the internet, they a digital artefact.

In these descriptions, I have sought to capture the sensory overload and conceptual depth of this exhibition. Revisiting these works collectively, I believe the curatorial vision and cohesive, thematic execution of the one-night only exhibition offered a layered experience that resonated as much in its discomforts as in its embrace of the digital and corporeal worlds. The title—Dithyramb—refers to the state of ecstasy associated with the Greek god of wine and madness, Dionysus, and later recalled by Nietzsche in his Apollonian and Dionysian creative dyad. The exhibition’s selection of artists, and curation, recognises that this concept is not a relic of the past, but a living, breathing force in the cyber world, in the revelry of nightclubs, and felt within the boundaries of contemporary flesh.

One could critique the lighting, which at times felt less than intentional, overexposing the room and dampening the atmosphere’s full potential. However, this may have been a practical limitation. Ultimately, Dithyramb proved to be a sensory experience not unlike the sharp, fleeting burn of an e-cigarette—intensely immersive, disorienting, and leaving a lingering addictive trace, a volatile memory of body and technology in motion.

Alma Aylmore is a Masters student in Museum Studies and Art History at the University of Queensland, with an undergraduate background in Anthropology.