Lying on the sand with her eyes closed, artist Cigdem Aydemir takes a photograph of herself. She is wearing a white veil, draped loosely around her shoulders, with the light fabric blowing gently in the breeze around her. Most prominent in the image are the tan-lines on the periphery of the artist’s face, indicating the absent veil. In the audio description of Aydemir’s photograph, Stasis (map of home) (2019), the artist is quoted as saying “identity is retrospective” and under a constant state of reconstruction. Aydemir draws from feminist philosopher Rosi Braidotti, who argues that we must think differently about ourselves as subjects and the constant deep-seated transformations we experience.1

Both Aydemir’s photograph and her quote capture the essence of Interfacial Intimacies, a touring exhibition curated by Caine Chennatt. Developed by Plimsoll Gallery and toured by Contemporary Art Tasmania, the exhibition explores notions of self and identity through portraits and anti-portraits, focussing on the “tensions of our networked personalities.”

Interfacial Intimacies is multilayered and curatorially paradoxical. The exhibition argues that identity, and by extension the artists displayed, are ever-changing. This challenges viewership and implies that audiences cannot know the artists or the intent of their work completely. Rather, we see the artist at a fixed point in time, mediated by innumerable confines, such as their materials, the gallery where their work is displayed, and the curatorial rationale that positions their work in relation to others. Instead of shying away from this contradiction and challenge to audience understanding, Chennatt embraces ambiguity, empowering artists’ and their subjects’ “right to opacity.” In turn this review highlights works that are especially effective in communicating the complexities of identity and fluidity of self.

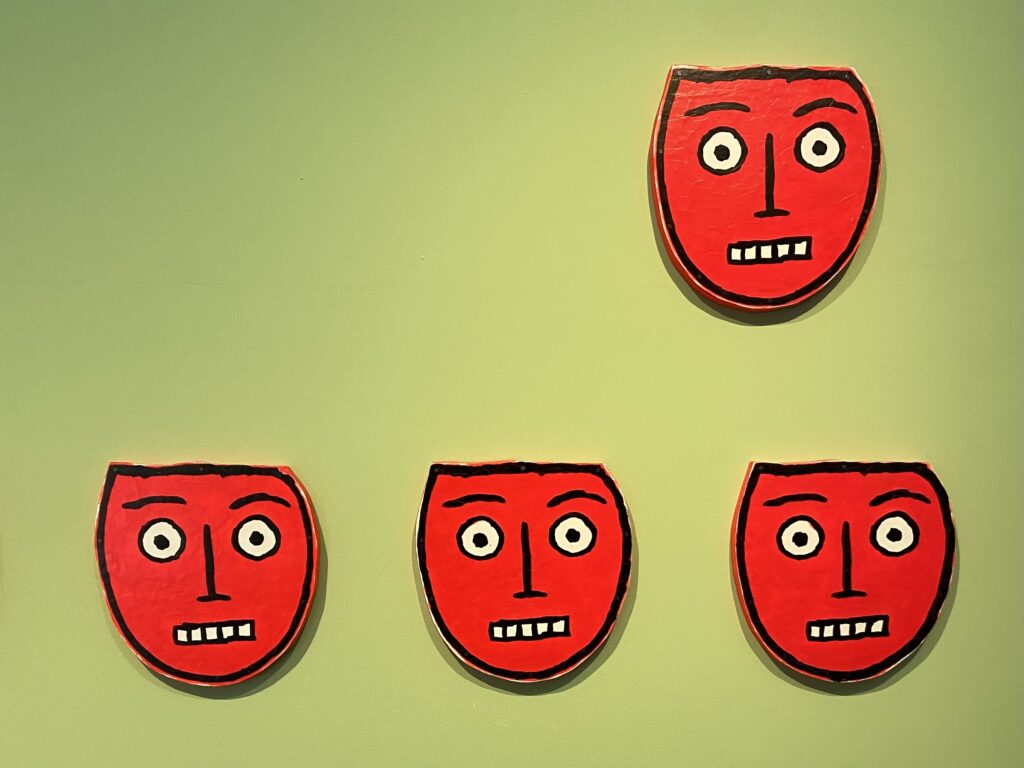

In the first room we are met with artworks that playfully consider the tension between conformity and individuality. Aleks Danko’s Incident – Ambivalence (1991/1992) is a series of bright, cartoonish, and disembodied faces. The ten red faces all hold the same indiscernible expression, evoking a ‘herd mentality’ and adopting the thoughts, behaviours, and actions of those surrounding. Similarly, David Rosetzky’s Gaps (2014) considers evolving and porous relationships between self and other. Their collaborative video work depicts four performers verbally and physically negotiating the spaces between themselves. Across various rehearsal locations, the cast move together in abstracted, gestural, and softly choreographed ways. The video illustrates the distance between the performers onscreen, and by extension the fissures between art and life, as well as performance and reality.

Omission, as a visual tool, is used in distinct ways by Bruno Booth and Georgia Morgan. Across nine screens, Booth’s video work Body Shots (2022) excerpts what is seen and understood about their disabled body. In the work, Booth has filmed their feet in various positions and locations. Through removing a larger context from these shots, the artist has created, in their words, “new and unusual bodies that float in space, quietly moving, and unapologetic in their existence.” The unknowable also operates in Morgan’s portrait, This dream is real (2021), wherein the artist stands alone on a silty riverbank next to an artificial palm tree. They wear a blue tarp and yellow netting draped around one shoulder. Initially forming part of a site-specific installation, Morgan’s portrait considers the enigmatic facets of intergenerational knowledge. Her portrait visually references the Malaysian kampong (village) where her mother grew up. In lieu of visiting the village, and gaining a first-hand experience of place, the artist drew upon conversations with her mother, culminating in a self portrait that is coloured by imagination and inference.

Continuing into the gallery, Country and kinship are broached by Cassie Sullivan in their self-portrait Country is calling (2021). In this work, the artist stands isolated on Nuenonne Country, surrounded by rippling, reflective water and a singular, swooping bird. Sullivan states: “As we exist here on the sand our ancestors have travelled for tens of thousands of years, we heal.” Sullivan’s work asserts their identity is inherently linked to their ancestors, using spiritual connections to reinforce personal and collective identity despite colonial disruptions.

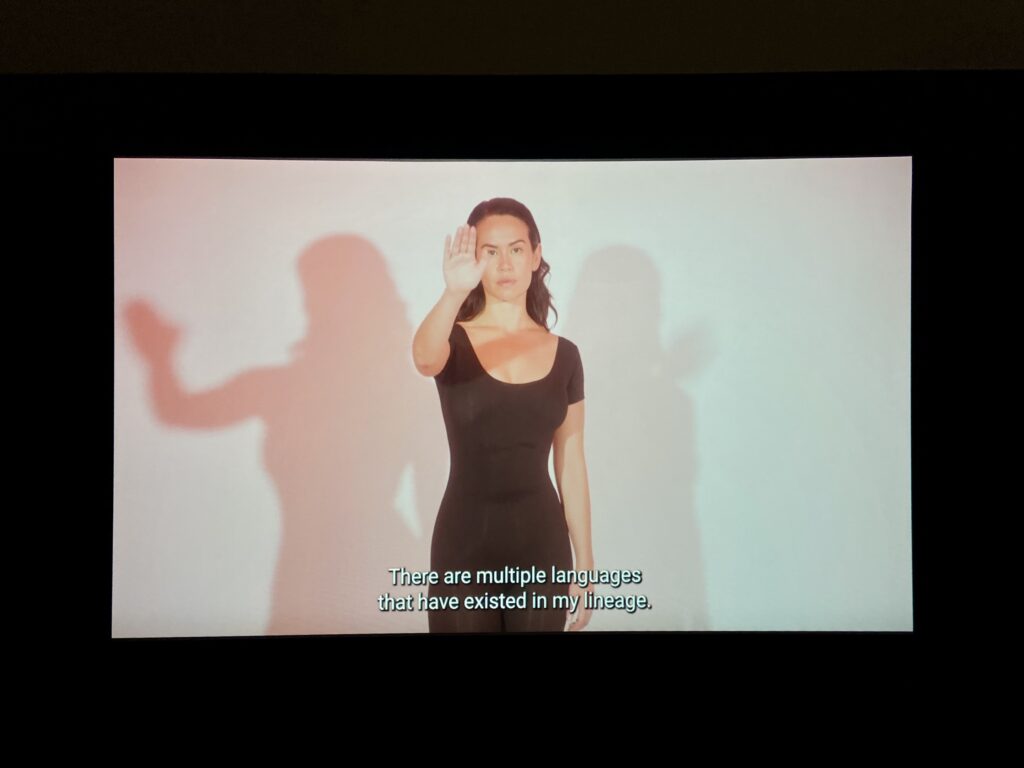

Finally, Amrita Hepi’s mesmerising video installation, Scripture for a smoke screen Episode 1: dolphin house (2022) encapsulates multiple themes explored within Interfacial Intimacies. Using the 1960s NASA ‘dolphin house’ experiment as a prompt, Hepi writes a letter to Peter, one of the animals subjected to the experiment, to consider surveillance and hierarchies of intelligence, language, and desire. Somewhat absurdist in style, Hepi questions the viewer’s gaze and uses Peter as an example of what happens when agency and autonomy are removed.Throughout Interfacial Intimacies, the artists choose what is shown or hidden, what assumptions are maintained or destabilised, and which subject/viewer relations are subverted or strengthened. In an exhibition that explores identity and the relational self as influenced by networks of communities and locations, it is important to be cognisant of the transience of our own sense of self. Returning to Cigdem Aydemir’s Stasis (map of home), although we should consider ourselves as being in a constant state of flux, contemporary art functions as a place of stasis where our multiple ‘selves’ can rest.

- Rosi Braidotti, “Writing as a Nomadic Subject.” Comparative Critical Studies, 11, no. 2-3 (2014): 163. ↩︎

Madeline Brewer is a curator and program producer. She works on Dungibara Country in Toogoolawah.