June Tupicoff’s paintings and pastels take us inside wallum country on K’gari (Fraser Island) and Mulgumpin (Moreton Island). Recent fires on K’gari are chronicled in paintings that move underneath the forest canopy, into areas difficult to penetrate. Others are more open and colourful, documenting the vibrancy and variety in these landscapes, undisturbed and unpeopled, but few include a horizon. With this internal view, Tupicoff embeds us into her own emotional experience of this landscape.

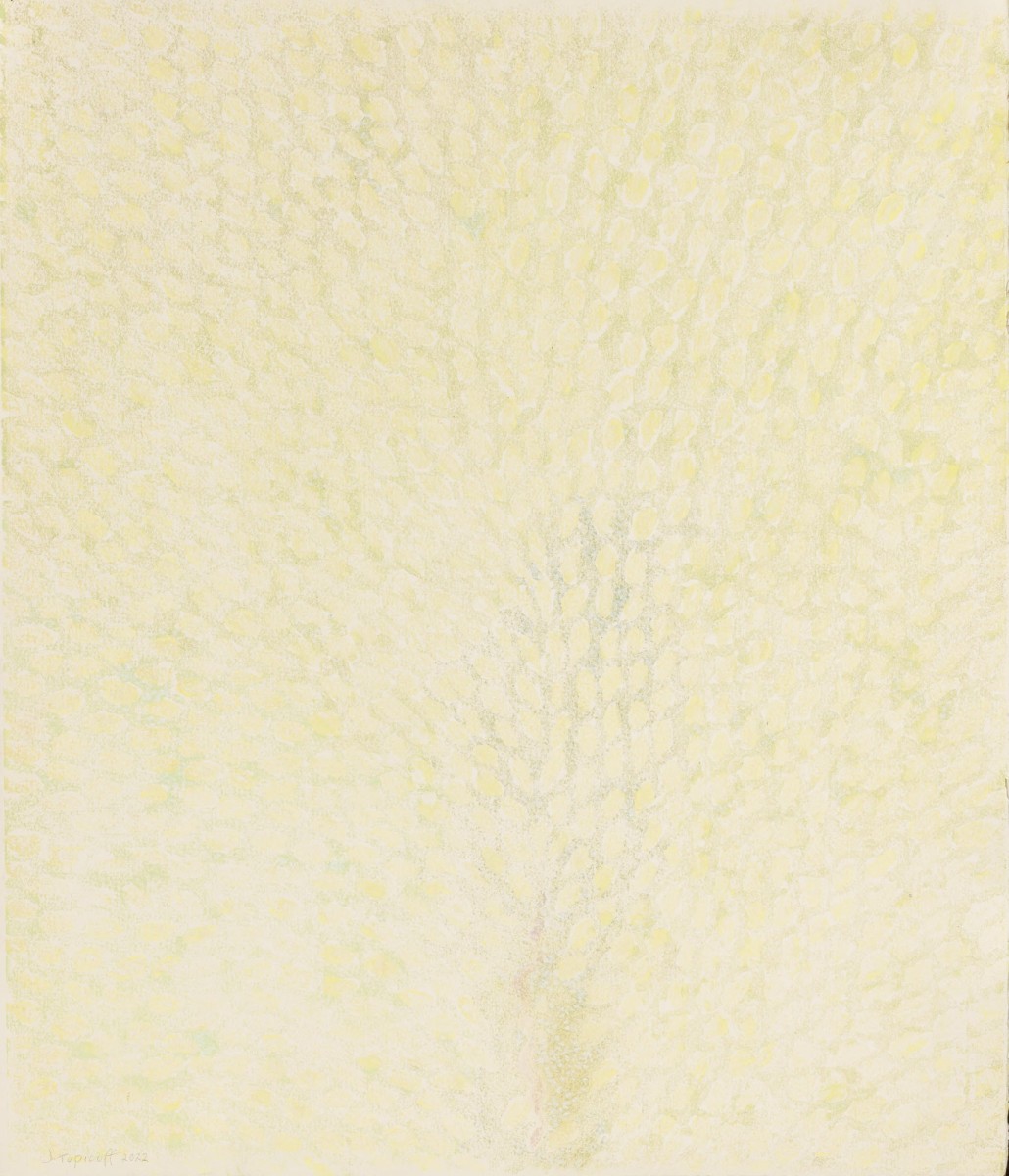

For much of her career, Tupicoff made abstract paintings. Her move into more representational works and her earlier oeuvre have in common an interest in light and shadow, and the sensation of moving air, atmosphere and surfaces. They capture time and experience in layers of paint. A single monoprint with pastel at the exhibition entry, Banksia (2022), evokes light and air with stippled marks that overlay pink and yellow with a hint of a shadowy stem, largely hidden, but nonetheless anchoring abstracted sensation to the centre of the picture plane. In its waxy finish and shimmer, I am reminded of her abstract paintings from decades past.

In this exhibition, there is a growing familiarity with landscapes that have occupied her for some years. The chronicling of Tupicoff’s bushland muse in these environmentally-diverse coastal areas reminds me of William Robinson’s similar dedication to one landscape for long periods, and even Claude Monet’s repeated depictions of his own garden; for each of these artists, it is light, shadow and atmosphere caught within their experience that becomes the real subject.

Tupicoff’s exhibition may be divided into two groups: the colourful lightness of unburnt areas, such as Wallum with waterhole (2022), and the charred undergrowth with light captured in patches of sand, such as Revelations of light (2022). In the latter, a rare translucency of the scrub is laid bare, as is the almost immediate regrowth, delicately detailed in green shoots amongst the charcoal. The colours are muted, yet the burnt areas are subtly nuanced with purple and lilac. Damaged vegetation is described in orange, pinks and deep green, alongside yellow blooms that rise miraculously from the ashes. Beyond the foreground and over a rise, the view into pristine bush is blindingly bright, with the sun-over-sand glare and a sense of squint-inducing normality. In contrast, Island landscape no.2 (2022) offers up a symphony of colour, a dedication to the different native grasses, vegetation and wiry scrubland growth around a dark waterhole. Landmarks (2022) sees different varieties of vegetation banded by colour in a landscape without landmark moments.

It would misread Tupicoff’s intentions to ascribe political views to these landscapes, yet in their dedication to a varied, fragile and sensitive environment, they are a reminder of how far Australian painting has travelled since last century when English-born artists, such as Frederick McCubbin and Tom Roberts, layered an emotional melancholy over the unfamiliarity of what they saw. Turning point (2022) is a detailed study of the forest floor, its darkness alleviated by light on the sand, tendrils of pale vegetation, and a greening smudge of potential new life. The title takes me to the existential threat of climate change, a sense that immersion in a landscape, which sustained Australia’s peoples for so many millennia, has a resilience that may weather the future, with or without human frailties.

Louise Martin-Chew is a freelance writer living on Quandamooka Country (Redland City) outside Brisbane. She contributes regularly to national art magazines and catalogues and has authored many books, most recently Margot McKinney: World of Wonder (Museum of Brisbane, 2022) and her first biography Fiona Foley Provocateur: An Art Life (QUT Art Museum, 2021).