Walking into Metro Arts’ Gallery One, I find myself overwhelmed by a sense of calm. Perhaps it is merely that I’m now in a room alone, having escaped the noise of shops and cafes outside. Or maybe it’s the meditative female voices of Laura Carthew’s The clouds have died (2020/23), drifting from behind an internal wall to draw me in.

Flux is an exhibition of moving image works by five previously unconnected artists, brought together via an open-call. The resulting exhibition explores how, through process and form, the moving image can be a powerful tool to experiment with time and space, enabling memories and images to be juxtaposed in order to create new meaning. There is a sense of nostalgia and imagination in the works by Holly Ahern and Eden Crawford-Harriman, Laura Carthew, Lyle Duncan, and Tyza Hart—old televisions, costumes and props, and storytelling are threaded through the exhibition. There is also a feeling of aimlessness, but with a glimmer of hope. Perhaps this is what happens when our understandings of time and space are disrupted.

Tyza Hart’s Pittsworth 1998/2018 (2018), playing on an old television, is the first work that I see. The video shows Hart riding a bike through their childhood neighbourhood; the sun glares through gum trees onto dry grass. It then flicks to Hart reading aloud from a notebook written by their 7-year-old self, telling stories of friends, places, and dreams. The notebook’s exaggerated handwriting and child-like drawings, framed by approving stickers and ticks from a teacher, triggers my own memories of primary school, writing, and telling imagined stories.

Hart describes their notebook as a “collection of autofiction exploring queer desire, existential malaise, social power dynamics, and dreams of alternative futures.” This earnest interpretation of childhood is an embellishment and Hart ensures we know this, disclosing: “I was 7 years old living next to a church in Pittsworth; I dressed my bike as a dinosaur.” Returning to the exhibition’s central theme, Hart uses the moving image as a tool to revisit the past, blurring their memories and the present by creating a collaborative work between two versions of themself, in two different periods of time.

Nearby is an installation by Holly Ahern and Eden Crawford-Harriman, whose collaborative practice centres around juxtaposing technologies and media in order to recontexualise existing objects and images. After experiencing the devastating 2022 floods of the Northern Rivers, they are now in the process of revisiting old ideas through a ‘post-disastrous’ lens. Their work No Tears (2018-2023) is an industrial-looking metal structure with two old televisions suspended from a thick chain and hook. On the screens, an abstracted video of bubbles floating randomly plays on loop. Through the installation, the artists remove the digital film from its intended context, bringing it into the physical world with an added sense of materiality. In doing so, they are able to examine the inbuilt obsoleteness of new technologies, and challenge the attached perceptions of distance and perpetuity.

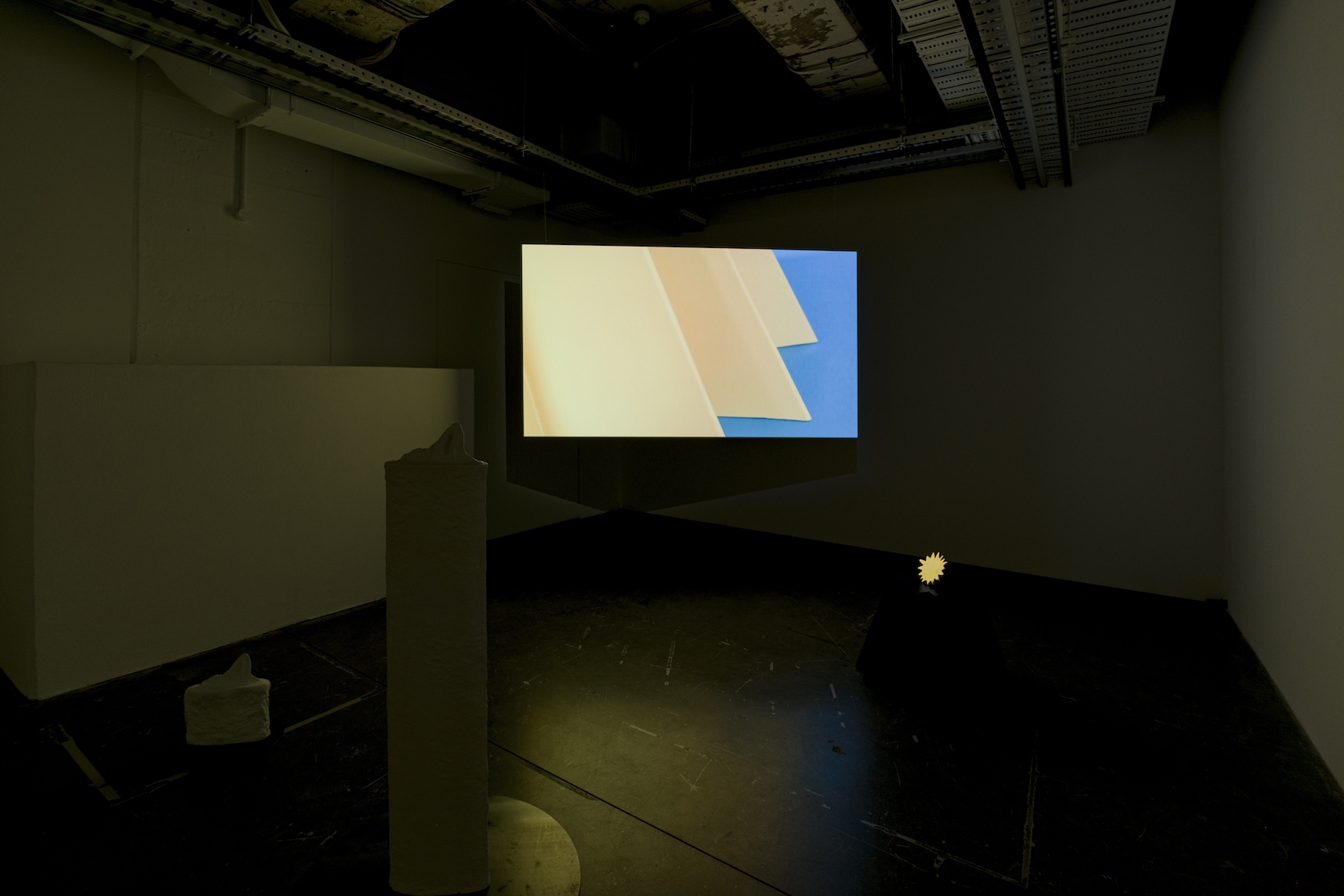

At the opposite end of the space is Carthew’s The clouds have died, a transcendent work of video, sculpture, and recited poetry. Clouds, stars, the sun—symbols of the sky connected to notions of death, rebirth, and immortality—are introduced as small sculptures. They are echoed in the film and again through words. Poetry is recited by three generations of women telling memories, both real and imagined, as well as referencing astrology, myths, and natural phenomenon. Lines such as: “I put my hand among the flames/I do not burn” and “My dead body wears a smile” create a surreal and ominous mood, full of contradictions, appropriate to the concept of rebirth and its inherent connection to death.

The final work is Lyle Duncan’s Space Supervised (2023). Split across two small monitors sitting back-to-back, it examines the boundaries between private and public spaces in our cities, and the ambiguity we collectively feel towards them. The video follows the artist exploring a Brisbane city rooftop. There is a sense of unease. Is he meant to be there, or is this space designed for someone else? Intensely examining his movements on the two small screens places the viewer in the role of security guard, raising questions around public control and surveillance and the parts we unwittingly play in enforcing these structures.

There is a clear eyeline from Duncan’s work to Hart’s film. The image of the adult man in Space Supervised, now climbing on the playground equipment of this vague public space, is juxtaposed with Hart recalling childhood memories by bringing them into the present day. Placing these works together offers a sense of hope. By removing the constraints of time and space, there is potential for new, better ways of seeing and interacting with the world. This is reiterated in the positioning of the second screen of Duncan’s work, in front of a window, so the audience can simultaneously see the screen and the view outside. Through the window is a commercial development that is part historic building, part newly constructed and highly manufactured quasi-public space, with its own set of rules about who can be there and how to use it. The juxtaposition is jarring, yet a perfect note to end on.

Lizzie Riek is an arts worker and emerging writer.