Volatile Terrain is the first iteration of The Condensery’s Harvest Biennial: a new programme that explores ecological concerns local to the Somerset Region and its communities. The Biennial serves as a development platform for regional artists, encouraging them to produce a new body of work in response to this theme, mentored and curated by Cara-Ann Simpson, to appear alongside works by other significant artists in Australia. Through its focus on soils and the interconnected ecologies1 that exist both beneath and above them, Volatile Terrain joins a recent raft of exhibitions that engage with a planet increasingly in crisis as a result of extractive, industrial and colonial human activities.

The Condensery takes its name from its history as a condensed milk packing facility, and the repurposed factory space is open and inviting. The centre of the room is occupied by Iranian-born, Meanjin/Brisbane-based artist Prita Tina Yeganeh’s My Soil Farsh شرف (The Shared Sacred Labour) (2024). The work immediately draws attention, and through it, we encounter soil in a very material and literal sense: an immense Persian carpet shaped from 45 kilos of discarded, loamy earth. The work offers a challenge to the commodification of carpet making, transforming labour into a collective ceremonial practice as women from Yeganeh’s community came together over a period of 145 hours in a month to grind the soil by hand into a rich, red powder. Yeganeh has also embellished this carpet by hand with a pattern of 3D-cut traditional farsh (a Persian carpet or rug) motifs. The carpet appears tactile, soft and inviting, and as it stretches across the pavers of the gallery floor, Yeganeh’s farsh asserts its own sense of space. Its edges define both a physical and emotional threshold that captures the sense of community behind its creation and offers a portal that reconciles the artist’s experience of fragmentation and dislocation from her homeland.

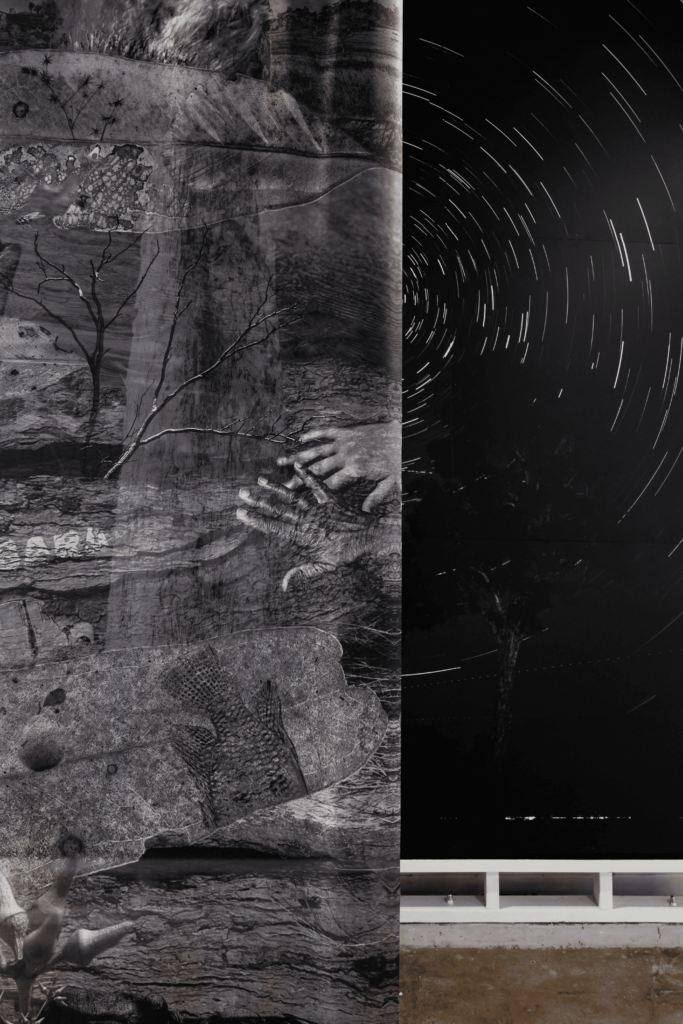

The exhibition ebbs and flows between locales and histories, and the foregrounding of regional artists provides a uniquely intimate focus. This intimacy is particularly enhanced by the gallery’s situation in Toogoolawah, a township with a population of only 1200 people. I feel this hyperlocal storytelling most keenly in the work of Naomi McKenzie, Elemental Reciprocity (2024). McKenzie’s complex photographic work layers images taken on Dungibara Country that share the story of the Masters family, the Traditional Custodians of the surrounding lands, who reside on the agricultural property neighbouring the Condensery. McKenzie’s photographic collage is printed on a floating, translucent silk screen suspended from the ceiling, and collates imagery of the landscape, leaves, the waters of the nearby Cressbrook Creek, and the sacred Scar Tree rooted in its soil. Behind the hanging silk swirls a slow-exposure photograph of the stars of the southern sky, recalling the passing of time. Depicting the Masters family history as inextricable from that of the landscape and the Scar Tree, McKenzie’s work attests to the family’s sustained spiritual connections to Dungibara Country across generations.

Volatile Terrain employs a thoughtful and dialogic curatorial approach, interweaving conversations between its works. Both Jim Filmer and Gooreng Gooreng artist Dylan Sarra’s works draw urgent attention to the loss of significant First Nations cultural sites through acts of colonial violence upon the land. In 1972 (2022), Sarra recalls the removal of the Burnett River Rocks, which contained culturally significant petroglyphs, to make way for the construction of a dam wall. These rocks were fragmented and dispersed amongst Queensland institutions, decontextualised from their original location and composition. 1972 works to reconcile this fractured heritage, taking charcoal rubbings of the original artefacts and reuniting them on a sheet of muslin cloth that evokes the original sandstone.

Similarly, Filmer’s photographic practice captures the transformation of the Maiwar (Brisbane) River following the construction of the Wivenhoe Dam. The work juxtaposes archival imagery of the dam’s construction against sweeping panoramas of the river, overlaid with translucent acrylic maps that chart the changing shape of the landscape. Together, Sarra and Filmer consider the ways that damaging colonial interventions were made to Country without consultation, imposing boundaries upon waterways and submerging Indigenous histories beneath them.

The conversations between the works sometimes take curious and unexpected turns. Cassandra Hodgins’s Symbiosis (2024)is captivating in its intricacy. It’s a series of four works depicted on scraperboard that draw upon her background as a nature illustrator. I am struck by the coalescence between the materiality of the work and its subject: Hodgins’s meticulous process of unearthing the image beneath the outer clay of the scraperboard is akin to an act of sifting through dark topsoil to reveal the sprawling, tentacular mycelium networks beneath. In her memoir, Finding the Mother Tree, forest ecologist Susan Simard looks to the “necessary wisdom in the give-and-take of nature—its quiet agreements and search for balance.”2 Hodgins’s work uncovers this symbiotic balance that exists between the unseen fungal networks and the ecosystems they nourish. Two boards depict a mycobiota of fungi thriving in a forest habitat. Another depicts an incandescent sprawl of mycelia reaching across the black canvas, while in the final work, an unlikely gathering of Australian fauna congregate to feast on these fungal offerings.

Hodgins’s work is positioned in a curious dialogue with Kate Geck’s embroidered textile panels, Mychorrizal Materialities (2022), which similarly draw upon the language of fungal ecologies. However, Geck’s work extends this premise from the subterranean to technological networks, in which delicate mycelia take on the guise of neural networks to explore the ways in which ecological metaphors can help us reimagine the symbiotic entanglements between human and machine intelligences. This dialogue makes visible the visual parallels between Hodgins’s delicate mycelia and these neural networks. To produce Mychorrizal Materialities, Geck worked with a machine learning tool she trained on 100 hand-drawings of Australian fungi. The generative adversarial network responded by producing thousands more newly generated images. Geck selected images from amongst these new offerings to embroider onto her textural, abstract silk hangings in glistening metallic thread. Geck’s work employs mychorrizal thinking as a counter to anxieties about the threats posed by machine intelligence, recalling Simard’s concept of the “wood wide web”, through which plants are able to transfer resources and information to their kin by way of underground fungal networks.3 Evoking this metaphor, Geck explores the generative and symbiotic exchanges that may occur between human and machine in their posthuman relationalities.

As the inaugural iteration of The Condensery’s Harvest Biennial, Volatile Terrain begins a vital dialogue connecting the hyperlocal with broader discourses within both an Australian and global context, celebrating and nurturing the rich artistic practices in the region. Concern for soils carries through this exhibition and depicts a planet in flux. Whether soil is Country, resource, ceremony, or archive, as a measure of our planetary impacts, Volatile Terrain urges us to tread lightly.

1. As Crone, Nightingale and Stanton propose in their introduction to Fieldwork for Future Ecologies, the term “ecology” encompasses not only environmental matters, but the entangled interdependencies between its human and more-than-human inhabitants; the technological and computational. Bridget Crone, Sam Nightingale & Polly Stanton (eds), Fieldwork for Future Ecologies, Onomatopee 2024, 13.

2. Susan Simard, Finding the Mother Tree, Knopf 2021, 13.

3. Kate Geck, “Mycorrhizal Materialities Positioning the Entanglement of Human and Machine Intelligence.” In ISEA2023 Proceedings, 85. https://doi.org/10.69564/ISEA2023-10-short-Geck-Mycorrhizal-Materialities.

Felicity Andrews is an emerging arts worker who writes, researches, and creates on Yugerra/Turrbal Land, Meanjin. She holds a Masters of Museum Studies and is currently undertaking a PhD in Art History at the University of Queensland. She works as a cultural mediator at the University of Queensland Art Museum.