At the beginning of November in North Queensland, we welcomed the petrichor that filled our sinuses and turned the landscape lime green as the tropical wet season began to set in. I breathed in deeply and squinted in the sun as I (sweatily) strolled to the TAFE campus at golden hour for the 2024 Diploma of Art student’s one night only grad show. The building had an undeniable fizz in the air as proud families and friends of graduates and the supportive local arts community gathered in the foyer where the culmination of two years’ work was on display.

Over the last two years, the staff coordinators of the Diploma have put their all into reviving this programme. This has paid off, with the TAFE beginning to build a new arts centre at their Pimlico campus. Hopefully a gallery is planned for inclusion in this new building, as the students and staff deserve a place that uplifts their works, rather than locations like the large foyer used for the current graduate show, which was evidently challenging to work with. It is the kind of space where attention is quickly swallowed up in the rush of the next thing, yet the staff did their best with what they had and created a sort of flow through the colossal collection of student work. As I floated around the venue over the course of the evening, there were works and themes that held me still. In a few stand out works that initially struck me as light-hearted, humorous, or gentle, artists explored death, decay, and discomfort.

One artist whose work felt playful at first glance was K Rodentia. Their diverse body of work was situated on large wooden stairs (one of many tricky display areas) and included wearable art, sculpture, 2D works, and a towering tree sculpture being re-built by tiny tree children. Very fun. What stopped me was a collection of five deeply personal oil paintings called My grandfather’s garden, where the artist attempted to capture and understand the complexity of their grandfather’s experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Each painting explored a stage of the insidious disease: an early depiction of their grandfather showed him happily in his garden. Next were bedside drawers containing kitchen items, a landline telephone with its cord chopped, a depiction of anger and denial in the form of a face tearing apart the canvas, and finally an almost unidentifiable figure in the same composition from the first piece. In addition to this imagery, the artist represented the disease with the use of an encaustic medium that grew from one painting to the next, eventually taking over the canvas completely. I didn’t notice its growing inclusion until considering the set of paintings as a whole, reflecting how the very early signs of the disease can feel obvious when you look back but unnoticeable in the moment.

In contrast to the holistic viewing approach required for Rodentia’s work, I had to get close to Rite of Passage by Ten Jorgensen to take it in. On a round black table sat three black shoe boxes, each with a 5 x 3 centimetre cut out on one side. As I brought my eyes up to this cut-out, eerie elaborate worlds came to light inside. One box possessed an abandoned house, another an overgrown forest, and the last, a cemetery. Jorgensen states that Rite of Passage was an expression of their navigation through grief and feeling frequented by ghosts. The artist has an ability to gently explore macabre themes. There was a delightful quality to boxes, perhaps achieved by the use of warm, intentionally-placed lighting that lit these tiny spaces in a curiously subtle way, teetering on the edge of playful and grim. I wanted to shrink down and sit inside these worlds, seeing in them a safe space to meet with my own ghosts.

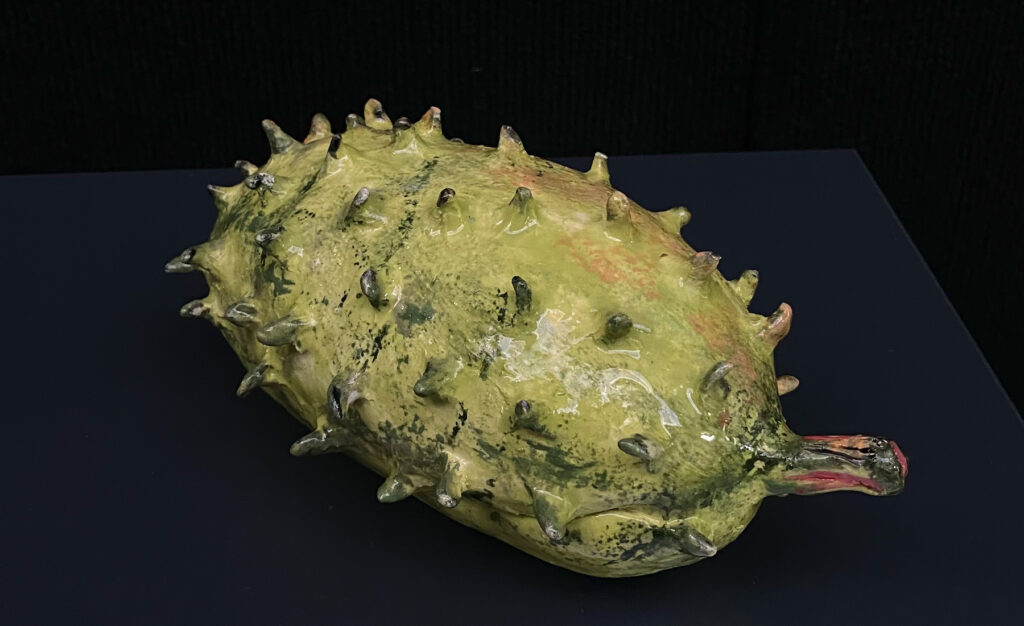

Working playfully with feelings of discomfort, Helen Page’s Paw Paw and Sour Sop ceramic sculptures, which are part of her ‘Strange Fruits’ collection, dive into her uncomfortable relationship with her neighbours. Splits in the pawpaw, like gashes on skin, and the unnatural gloss finish on both pieces created a sense of unease. Page’s use of underglaze was impressive and striking: the vibrant, tropical undertones made the sculptures feel familiar and homely, while their pairing with muddy greens indicated rot. The artist didn’t disclose much about these neighbours other than small hints in her humorous didactics. In turn, these sculptures left a lingering, rotten nosiness that I haven’t yet shaken.

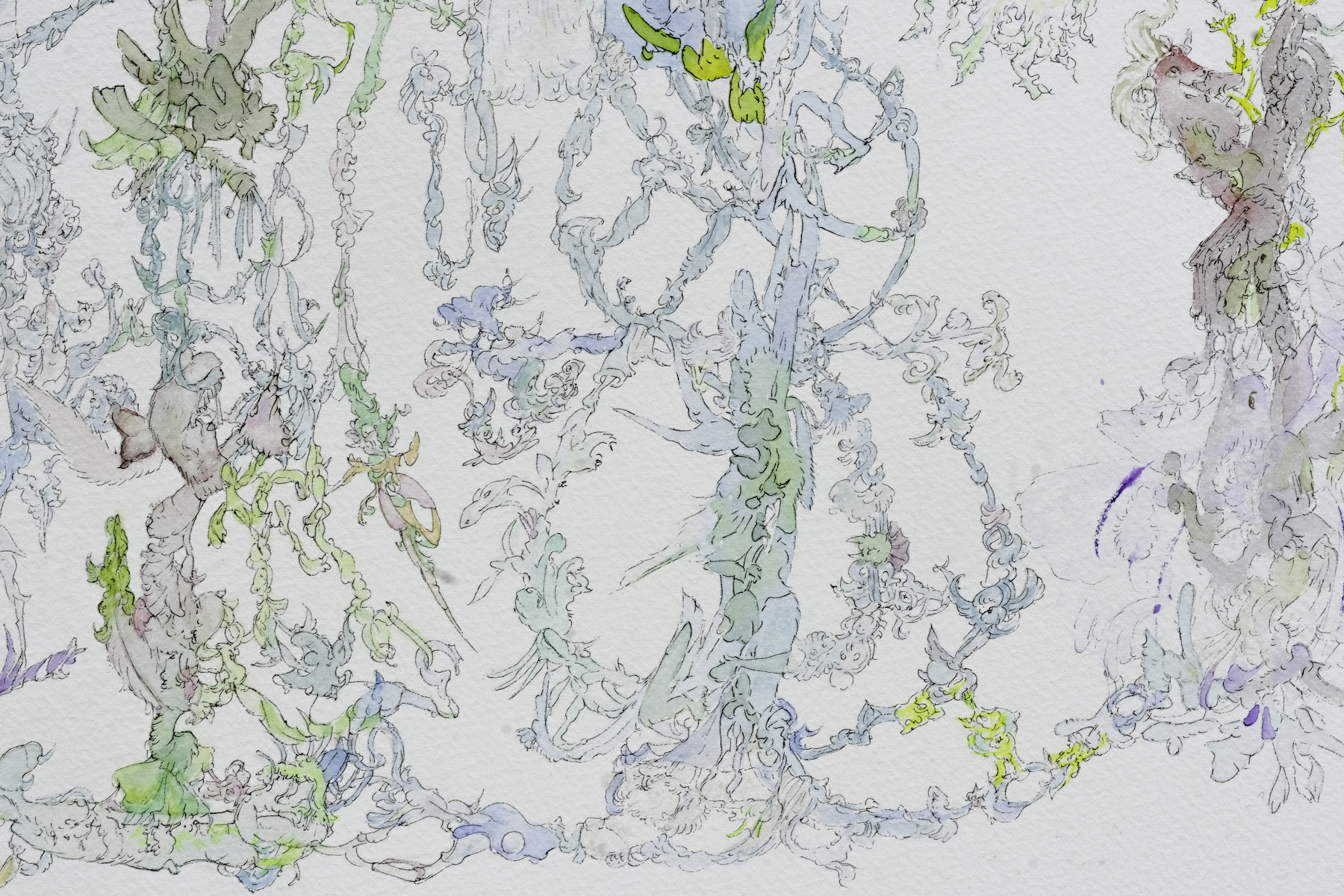

Also rotting were the bodies in the crocodile’s belly of Amanda Speare’s drawing What Lies Beneath. One of four skeletons stands upright, morphed within the suit of a crocodile, raising the question of who is really in charge. Speare’s work usually revolves around biology and she often depicts flora and fauna with a scientific eye. This was evident in her slowly stitched artist book Feathers, Ferns & Other Finds, a beautifully hand-sewn, bowerbird-like collection of bits and bobs. This difference from her usual work is what also made What Lies Beneath so striking; it stood out from her body of work for its skewed, bold nature. The jump from an intricately sewn fern leaf to a completely cooked and potentially carnivorous person in a crocodile costume is the ‘inspired by nature’ take I can climb onboard with.

Expanded Lemonade coverage of 2024 graduate exhibitions is kindly made possible by Lemonade’s Patreons — including our newest Patreons Andrea Crosser, D Harding, Rosemary Tamas-Cao, and Patricia Olazo — as well as generous contributions from anonymous, Ruth Grieg, Leanne Kelly, Sandy Lidgett, and Charmaine Lyons. A special thank you to Merilyn and Stephen Mayhew for sponsoring a full Grad Show review.

Baylee Griffin (they/she) is an artist based in Gurrumbilbarra (Townsville, QLD).