A group of French historians once proposed a longue durée approach to history, where things like ancient geology and incremental shifts in climate could be seen as swells in an ocean of time. The minutiae of human lives, politics, economy, and culture at any particular moment were, by comparison, ephemeral froth on a cresting wave. This idea of placing the history of so-called great men in a wider context emerged in the interwar period, when, in Australia, the European colonial project of forcibly assimilating Indigenous peoples led to what would infamously become known as the Stolen Generations. Yet Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had known for millennia what those French historians were now proposing to the academy: the human story is surrounded and supported by the cycles of the natural world.

In a new show at Milani Gallery in Meanjin/Brisbane, Robert Andrew’s works continue to unearth his own denied or forgotten family histories, while also articulating a distinctly digital connection to Country. A descendant of the Yawuru people near Broome, Western Australia, Andrew only learned about his Indigenous heritage in his teen years. It was later still that he moved across Australia from Perth—first to Newcastle, then to Brisbane—and began to explore the hidden branches of his family tree. As an exhibition, new eyes – old Country spotlights an Indigeneity in tune with those wider, natural swells of time.

The first work encountered upon entering the gallery is two lines of aluminium rectangles wrapping a corner of the wall, with erosion forming red Yawuru words: wulani yinamirlgan buru. Water waking country (2025) appears to be an extension of a work commissioned as part of rīvus, the 23rd Biennale of Sydney in 2022. Both were created with what Andrew calls a palimpsest machine—a modified 3D printer repeatedly washing away layers of earth and white chalk to reveal hidden text inside the ochre pigment. The earlier work was dynamic, with the machine moving methodically along the walls of the MCA. This version shows the text already revealed, but the work similarly considers the slow and inexorable. It brings to mind what I know as a Chinese phrase, “constant dripping wears away stone” or 滴水穿石. That incremental change, with layer upon layer of minor erosion slowly forming significance, makes Andrew’s work all the more resonant.

new eyes – old Country (2025), the exhibition’s eponymous work, is its star—if it’s designed to have one. A doorway frames the angled flat screen for a moment before revealing, as you enter, a double height ceiling with the work’s long track mechanism dead centre. A stunning drone shot traces what could be roads in the Kimberley, with the Yawuru word nagula (salt water) digitally superimposed on the roads. Charcoal pieces tied with string drag behind the screen as it moves across its programmed path, drawing lines along the gallery wall that perhaps mirror the road’s shape. Its triumphant framing gives the work a grand scale, which contrasts with the scattered bits of broken charcoal littering the floor.

You could easily miss the other work in the room, almost hidden in the wings, through the thin entry to the left of Gallery 2. A murky tank sits atop a pedestal in a triangular space, but peering closer reveals a 1920s-era typewriter suspended within. The work can seem to pulse as bubbles rise in the salt water, fuelled by an electric current running through the machine to hasten its corrosion.

The work’s sardonic title, Some language for you, Mr Neville, seems to reference early Australian public servant and eugenicist Auber Octavius (A.O.) Neville. As Western Australia’s Chief Protector of Aborigines from 1915 to 1936, he oversaw his genocidal policy of stealing children to speed up assimilation in the Kimberley. Though put into practice earlier in some places, the policy was formally adopted nationwide after Neville’s words and ideas took several Canberra conferences by storm. He advocated the nation “merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there were any Aborigines”.

There is a distinct feeling of anger here, though muted. Cut off in a small, slightly oppressive side space, the bubbling tank seethes as electrolysis slowly eats away the tool of a hateful past. Andrew has previously referenced Neville in his practice. His 2022 work Moving beyond the line at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art (IMA) had water drops melting Neville’s racist 1947 book Australia’s Coloured Minority into oozing blood-like ochre. Some language is less visceral, but more searing.

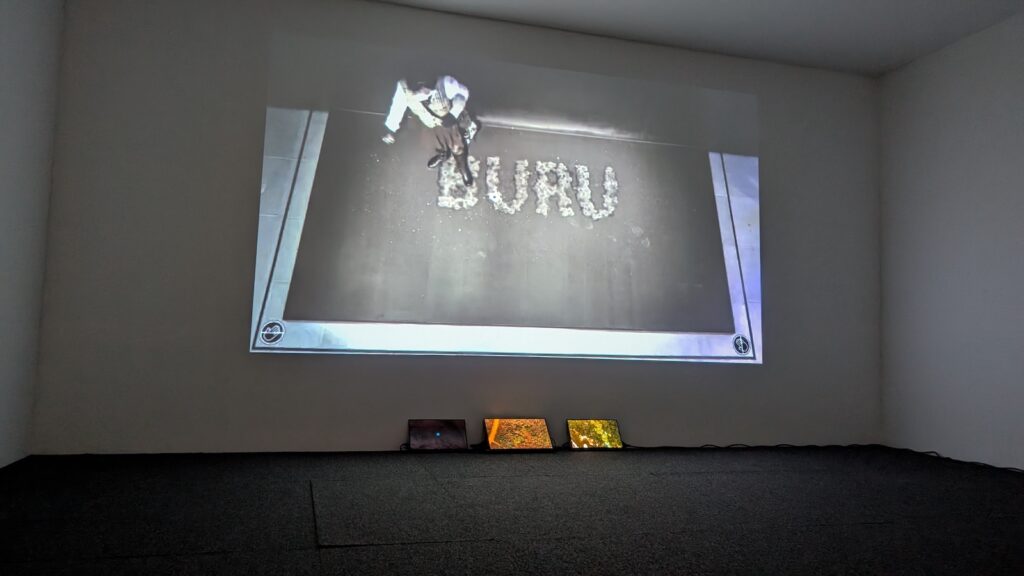

Andrew also makes a sly critic upstairs in the short video work To see without (in)sight – terra nullius (2025). What appears to be greyscale CCTV footage from the Science Gallery Melbourne is projected on the wall, showing a person deliberately walking over Andrew’s 2023 work Between language and country, despite the signs saying not to touch. The work had salt water and earthen red iron oxides slowly dripping from above, building a Yawuru Ngang-na word gifted to the artist by the Mabu Yawuru Ngan-ga language centre. The word, translated on the exhibition’s small information sheet, is buru meaning “country, everything you see, time, and space”.

In the footage, the vandal turns to consider their destruction of the word, adjusts some sort of headwear, and turns back to look one last time before walking away. Beneath the projection are three slow moving drone videos of brightly coloured land.

What struck me about new eyes – old Country was its reserve. Milani Gallery offered just a slim page of titles and a few translations, with no didactic panels or background information to aid a viewer with what could look like a self-referential exercise for those in the know (and a mystery for the rest).

Or not. Perhaps the point is to encourage non-Indigenous viewers to do the work and find a translation themselves. To reach out rather than expecting all the answers. Perhaps it’s about finding yourself within that wider history. Trying to glimpse the broader swell of time past the froth of our present moment. Or perhaps not.

Zoe Devenport is a writer, historian, and journalist, formerly at the Mackay Daily Mercury.