Dye sublimation on mirror glass. Photograph: Katie Bennett.

The physical changes to Brisbane are easy to observe using photographs taken over the last 100 years. However, the other ways in which the city and society have changed are not as visible. In the Museum of Brisbane’s new exhibition of photography, the level of this change is poetically exposed. New Light: Photography Now + Then traces the seismic shifts in social access and understanding that have taken place since amateur photographer Alfred Henrie Elliott (1870-1954) was documenting developments in the city between 1890 and 1940.

The way that Brisbane has expanded and, importantly, society’s ability to embrace diversity in its outlook, is integral to seven contemporary artists’ responses to Elliott’s century-old images; their examination of the Elliott Collection opens this treasured archive within the Museum of Brisbane collection to fresh interpretations that reflect the distance we have travelled.

The commissioned artists range, in true Museum of Brisbane style, from established and known contemporary photographers like Marian Drew and Carl Warner, through to emerging talents Keemon Williams and Nina White. This selection, by curator Elena Dias-Jayasinha, required only that the photographers, like Elliott, have a personal connection to Brisbane.

The new works engage with Elliott’s historical photography yet reflect the artists’ particular interests. As portals of change, each of the seven bodies of work encapsulate the distance travelled in terms of social mores and contemporary attitudes, the impact of social context, and the viewpoint of the person behind the photograph.

Marian Drew’s practice has revolved around the natural environment and its relationship with new generations. She sought out Elliott’s images of natural environments similar to those in which she spends time, like Tingalpa Creek. Drew utilised Elliott’s negatives, removing key sections to expose how the viewer is integral to the way such images are ‘read.’ Printing this old imagery onto mirrors means gaps open to the viewer, who find their own likeness in the landscape. The way that images are always in flux, reformed as they are seen, is given visual clarity here.

Carl Warner, whose work highlights detail in the urban landscape, found a pattern in Elliott’s images that he attributes to Elliott’s compositional default. Warner created five progressive images, built on a photograph Elliott made in 1893. In the third image, Elliott’s compositional pattern is isolated in a colourful abstraction. Within the fifth iteration, this underlays Warner’s new photograph of a similar bush landscape. This final iteration joins Elliott’s work directly to Warner’s, also bridging the distance between photographer and viewer. Warner suggests that the image hovers between them, in the space of having been taken and seen, ‘like sharing a breath’.

JoAnne Driessens found herself gravitating, in Elliott’s archive, toward the Bunya trees around which Aboriginal ceremony brought groups together in Queensland. Often the view of these trees in his photographs was glancing and partial. Her photographic response places the bunya trees front and centre, reorienting the view toward her Aboriginal focus in the landscape.

Tammy Law has overlaid images of her Chinese family on Elliott’s images, reflecting their historical importance in Australian history. She recreated his images with her own family images, letters, and notes; adding translucent three dimensional elements to evoke the layering required to see these alternate histories.

Keemon Williams responded with a ‘posthumous collaboration’ with Elliott, enlarging and reworking a photograph of horses at Point Danger, using new technologies to veil and reinterpret the scene like a futuristic video game. The sculptural presence of a large frame propped in the exhibition space catapults the past into the future.

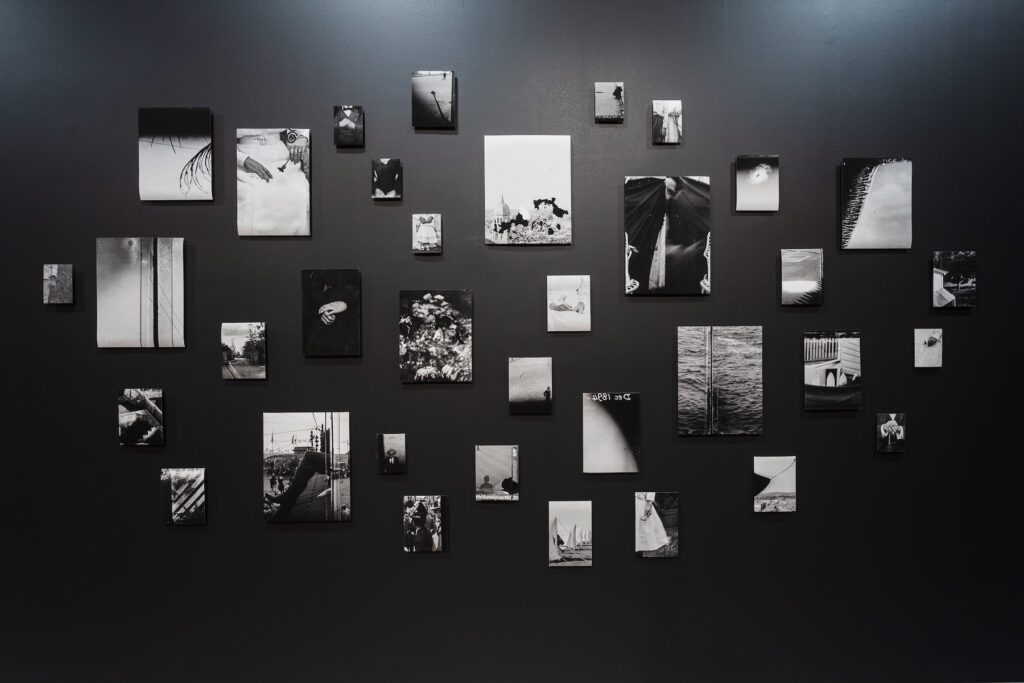

Nina White’s practice explores family, memory, and history within the archive. Her response examines the accidental aspect of Elliott’s images to highlight the personal, the incidental, and the damage inflicted by time and the handling of the glass negatives themselves—their blurring, fingerprints, and cracks. In cropped images of hands, blotched cityscapes, and faults, she reconstructs the collection in a way that teases out the capture of time and its fragility.

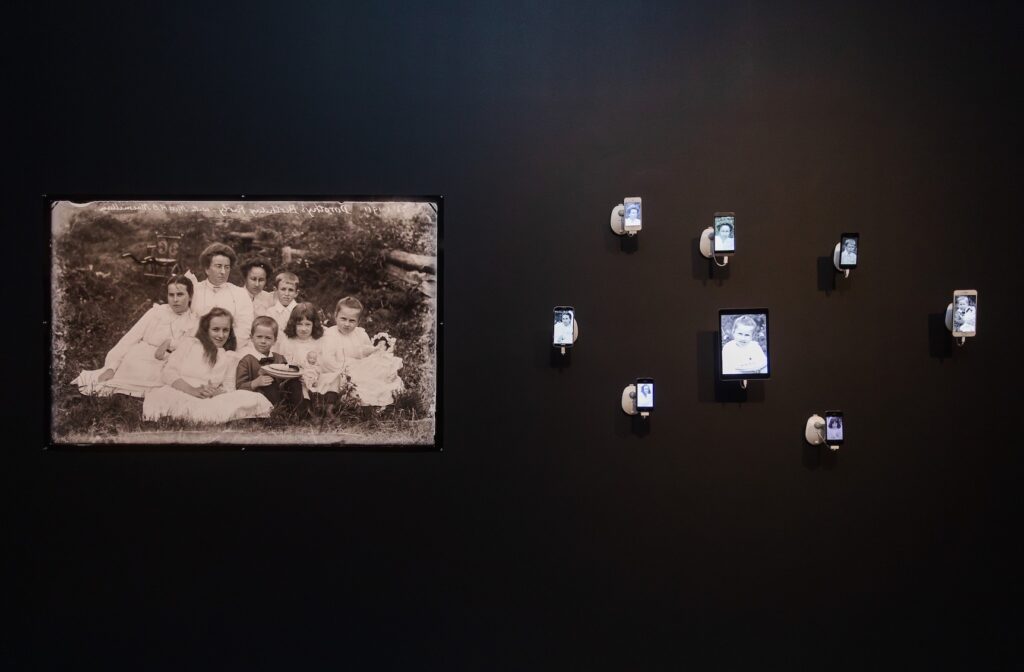

Joachim Froese was drawn to images of family in Elliott’s collection. He identified a group celebrating the ninth birthday of Elliott’s daughter, Dorothy. Froese dissected the image to reflect contemporary gender norms and rehoused its elements on smart phone screens, taking the birthday girl from an unhappy place at the edge of the portrait into the centre of the group. Contemporary technology represents this work adjacent to the original, with its transformation tender and poignant.

This innovative exhibition is illuminating, not only describing changes in the last century but the power of history to open personal narrative to societal insights. A selection of Elliott’s historical images is also available for public viewing, with the broader photographic community represented in the adjacent Viewfinders exhibition, which describes aspects of Brisbane you may have seen and others overlooked—until now.

Louise Martin-Chew is a freelance writer living on Quandamooka Country (Redland City) outside Brisbane. She contributes regularly to national art magazines and catalogues and has authored many books, most recently Margot McKinney: World of Wonder (Museum of Brisbane, 2022) and her first biography Fiona Foley Provocateur: An Art Life (QUT Art Museum, 2021).