The tag line for the Brisbane Institute of Art is “a place to make art.” And it is the embrace of the art-making—materials, technique, and processes—and all makers that is evident in the annual exhibition of graduating students. The densely-hung display fills both levels of the BIA’s spaces. Work is drawn from the over thirty courses available with well-regarded tutors, from weekends to short workshops to semester-based classes.

Brisbane’s art history is reflected in the prizes awarded in this year’s exhibition, with winners for the two prizes offered reflecting the legacies and memorialising significant individuals who were involved in the development of this privately run, not-for-profit art school. Even with the awards, the BIA does not seek to establish a hierarchy. People are here to make art and share collegiate experience—without looking over their shoulders at what might attract attention and applause.

The Metcalfe Prize is the major award, with an overall winner and highly commended in categories for sculpture, ceramics, painting, gold and silversmithing, mixed media, and drawing. It honours the memory of Nona Metcalfe (also known as Nona Waldie, 1915–1989), who was an artist and one of the founders of the BIA (which began as The Brisbane School in 1977 after being cut adrift from the Australian Flying Arts School due to loss of funding, also 1977). The gift of Metcalfe’s modest estate in 1989 was, according to BIA President Linda Back, “a lifeline which really got the BIA back onto its feet.” The second prize, specifically directed at printmaking, is named for Wim de Vos (1947–2018), who was an educator at the BIA and a well-known Brisbane artist. Each of these awards offers the recipient a semester of BIA classes, the Metcalfe in a medium of the winner’s choice, and the Wim de Vos in printmaking.

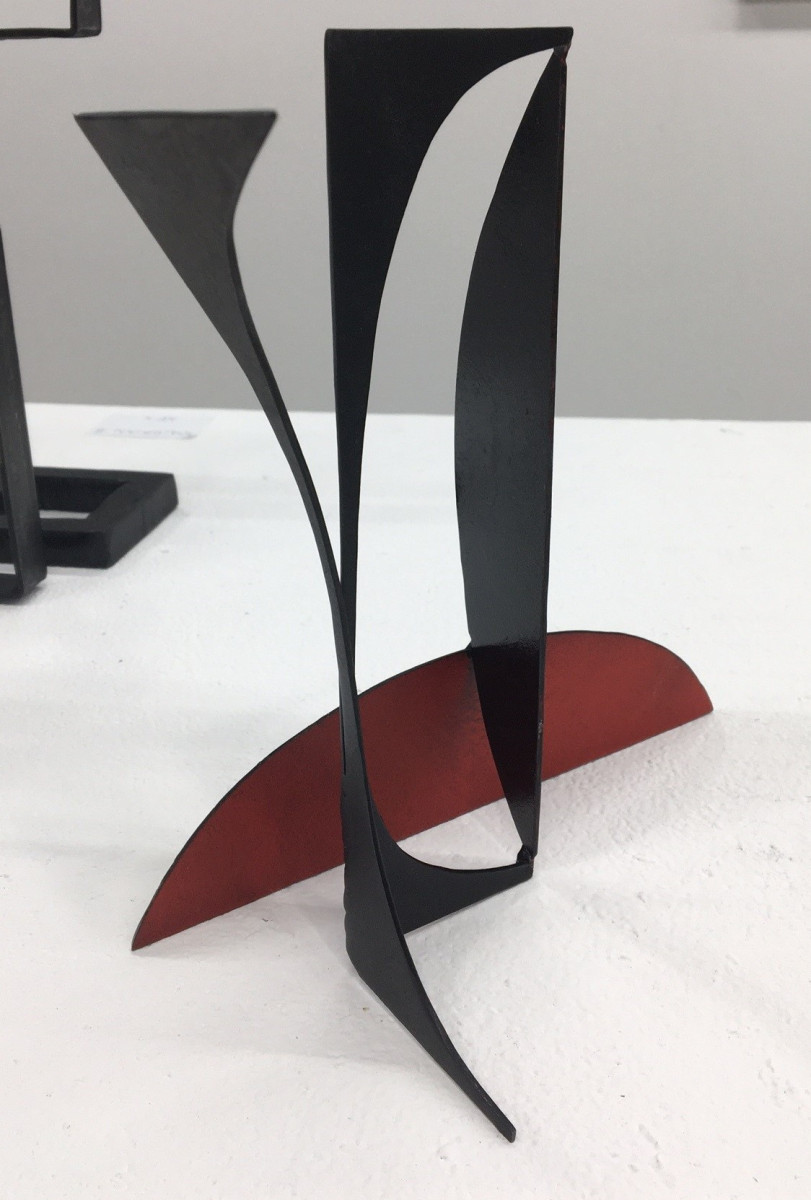

Sculptor Stephen Newton judged this year’s Metcalfe Award. He said: “The judging was extremely difficult because, if you go on technique alone, most works tick all the boxes: students understand material and process. If it’s painting, they understand your basic palette and brush mileage and more. A lot of people that go to the BIA are mature; so they bring valuable life experience into the making of their work.”

The major award Newton directed to a drawing by Ann McDonald. Titled Portrait of my sister, it depicts an embroidered blouse, larger than life, which floats on a dark background, investigated through its densely drawn marks. For Newton, “In this rendering it carries the emotive weight of a search, revealing the person through the garment. The material and the process work together.”

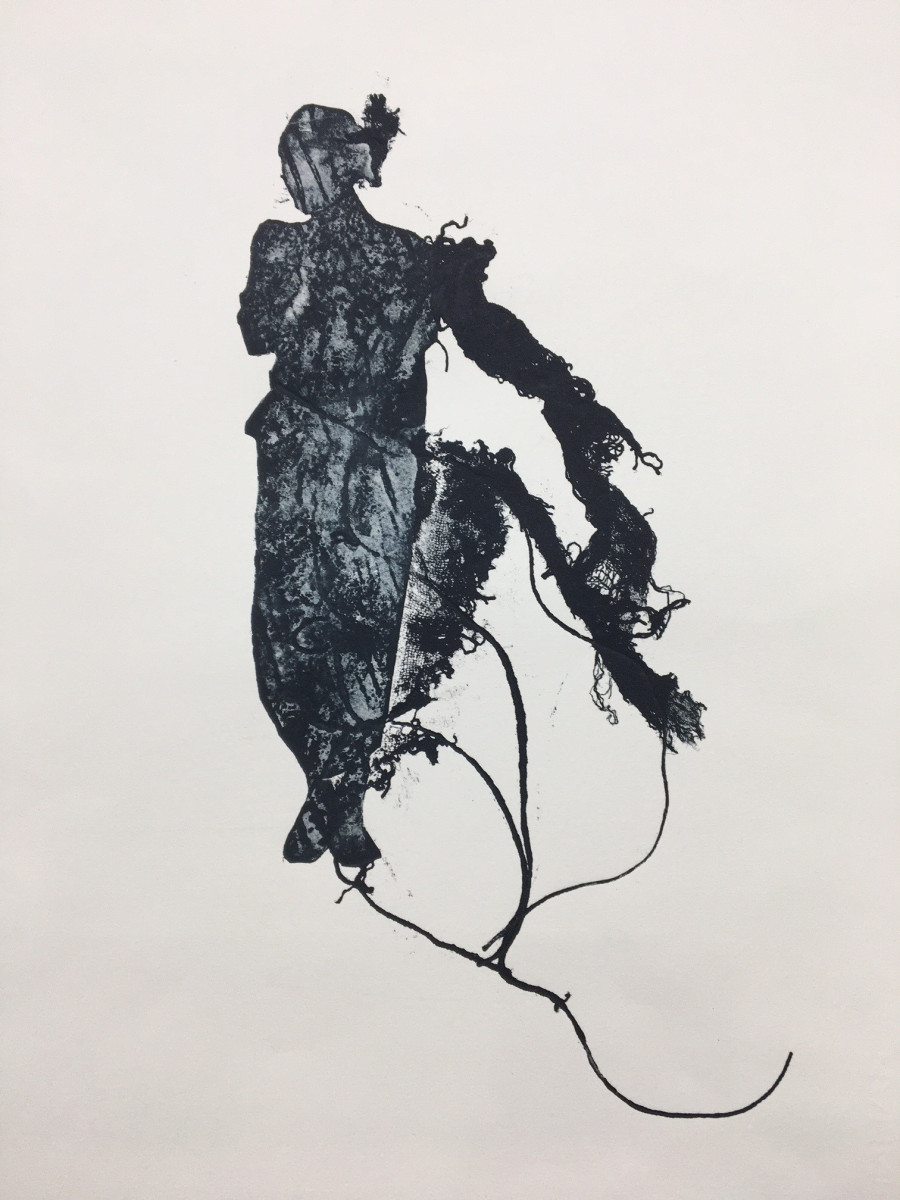

Another BIA tutor, printmaker Glen Skein, judged the Wim de Vos Award. It went to

Ali Bayne for a Chine collé and collagraph print titled Musing. In this small print, rich levels of detail and associations are drawn with a background of printed music, overwritten with black pen lines and a contrasting gold foil finish placed delicately, like light touching a surface. Skein said that he found in this work, “a high degree of experimentation and versatility.”

There is an overwhelming quantity of work in the exhibition, which speaks to the BIA’s many classes and open doors. The work presented differs to the more selective and often conceptually-driven work of university schools. Offering facilities for building skills and enjoying the process is the BIA’s focus, which draws all levels together in these exhibition spaces (beginners with intermediate classes, and media across the board). Art of significance possesses both technical and conceptual strength. The latter varies in this selection, but is present, particularly in those works singled out for awards.

The democratic approach to the exhibition speaks to the freedoms afforded to these students, working outside assessment strictures, and is tied to the reasons the BIA was established. President Back tells me that the BIA obtained accreditation for its Diploma Program for a time. However, they found that this was not what people wanted. “Most people want to come and learn how to do art. Classes become groups and they stick together. It’s collegiate, forming community rather than attaining a qualification.”

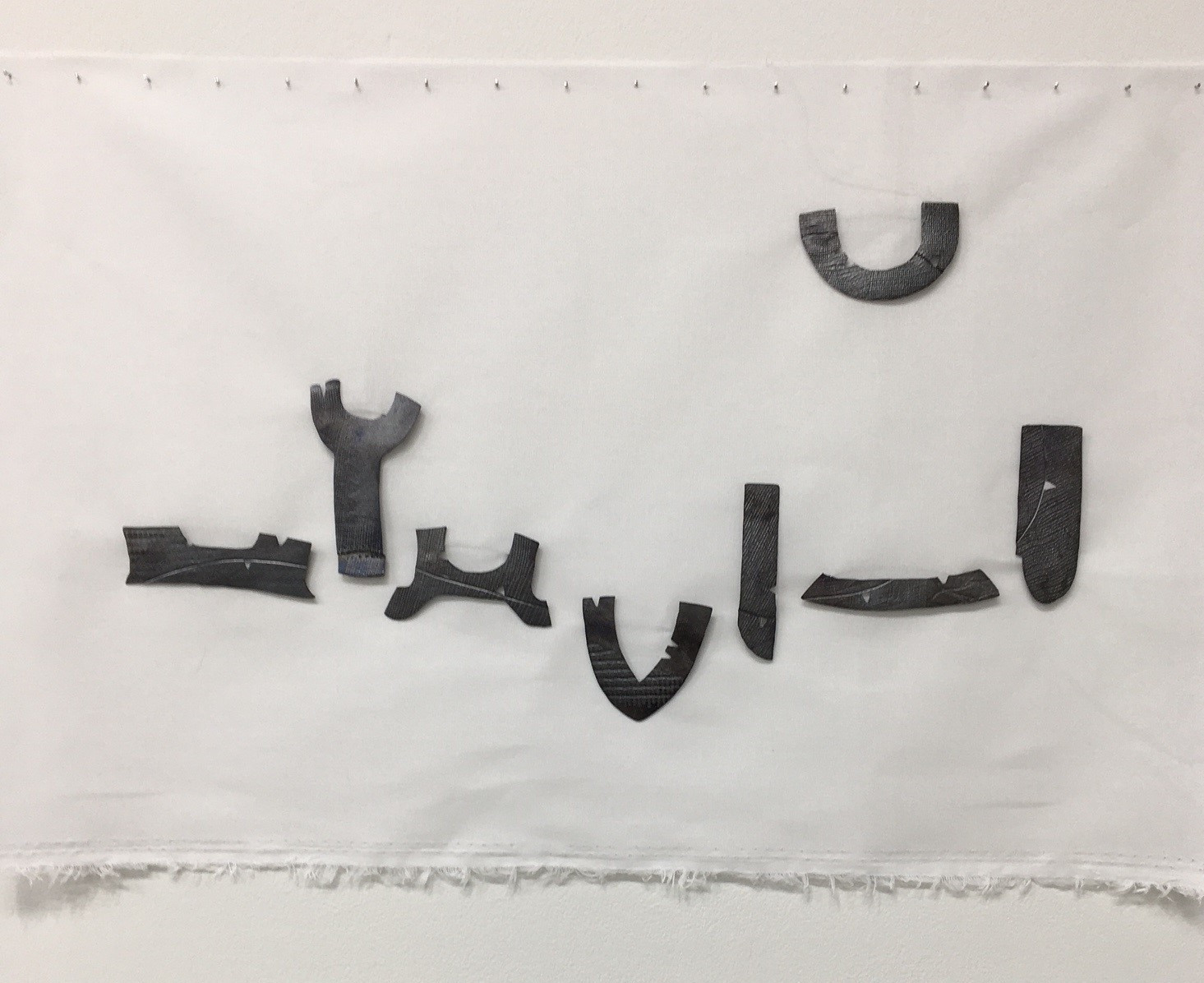

The watercolour sections display a significant mastery of the medium. Judy Keogh’s particularly fine sculptural assemblage was highly commended in the Metcalfe Gold & Silversmithing section. Broaching landfill: facing up to fast fashion was presented like a wall installation, punctuating the white background and imprinting materials with shapes extended with pattern and surface markings.

The exhibition has an appealing lack of pretention in its entries and award winners. This avalanche of creativity presents individuals who use artmaking to make sense of their own world in a way that may sit outside their everyday existences or professions. For that reason, the BIA performs a crucial role in the Brisbane art ecosystem, with its strengths of technical and skills-based practice well represented in this selection of work.

Expanded Lemonade coverage of 2023 graduate exhibitions was kindly made possible by Lemonade’s Patreons and generous contributions from Alex Baxter, Amanda Bennetts, Kylie Harries, Lynn Hughes, Kit Kriewaldt, Pippa Macgill, Merilyn & Steve Mayhew, Doug McNeill, Annelize Mulder, Jane Orme, Alethea Richter, Monica Rohan, Adrian Smith, Gavin Smith, Leisa Turner, Hannah Williamson, and Nadya Wilson.

Louise Martin-Chew is a freelance writer living on Quandamooka Country (Redland City) outside Brisbane. She contributes regularly to national art magazines and catalogues and has authored many books, most recently Margot McKinney: World of Wonder (Museum of Brisbane, 2022) and her first biography Fiona Foley Provocateur: An Art Life (QUT Art Museum, 2021).