Entering Venice during the opening weekend of the Biennale is an intensely overwhelming experience. Hundreds of thousands of spectators, clad in sneakers and tote bags, weave their way between venues, fueling themselves with caffeine and vino as if they could provide the energy needed to take in every spotlight exhibition, national pavilion, or public program. Consumed by this bustling, ancient city, you find yourself wandering down narrow cobblestone alleys in anticipation of stumbling upon yet another activation of La Biennale di Venezia. Capturing the attention of those who travel far and wide to one of the oldest and arguably most notorious international art events is quite the challenge.

This year’s 60th instalment, Foreigners Everywhere, led by Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa, made it clear that the battle for attention is more rampant than ever before. Within the 87 national pavilions that make up half the event, curators and artists leaned heavily into futuristic, sleek technology, sometimes at unnecessarily grandiose scales where the sincerity of their message risked being overshadowed by their cost of production. Installations aimed to engulf viewers entirely, employing optically assaulting vibrancy, multi-sensory experiences, and booming surround sound. It is within this ‘theatre’ of the exhibition that many national pavilions struggled to effectively address contentious topics. Often, they fell short by what I sense is a presumption that their efforts to reconcile issues were fruitless and unproductive. When you see yourself as merely a drop in the ocean, why not provide the moth with more lamp instead?

The Biennale’s spectacle-driven trend prompts questions about whether its structure overlooks the independent exhibition’s potential to not only capture the interest of viewers but also to offer solutions, draw conclusions, and establish points of connection within the space itself. The answer to these questions comes in the form of redeeming exhibitions that were unpretentious and pared back. This understated approach emerged as a successful tactic in meaningfully engaging the Biennale’s audience, as evidenced by Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist Archie Moore’s Australian Pavilion presentation, which was awarded the Golden Lion: an Australian first for such global recognition.

I sat down with Archie and curator, Ellie Buttrose, on the first day of the pre-opening. As we settled in for our chat, Archie busied himself making coffee while Ellie and I chuckled about the humour of three ‘Brisvegas’ locals finding themselves in Venice. Feeling comfortable in the presence of two beloved and familiar faces, I confessed to Ellie, “I think I can speak for the entire Brisbane art scene when I say we are incredibly proud to see both of you here, and what you have accomplished.” Ellie, calm and composed, offered a grateful shrug in response, replying, “It’s great to see everyone celebrating Archie.” While this might seem like a passing remark, the casual yet genuine acknowledgment of the artist’s significance (rather than her own) by the curator, speaks volumes and lays the foundation for understanding the pair’s ethos toward ego—or rather, the lack thereof.

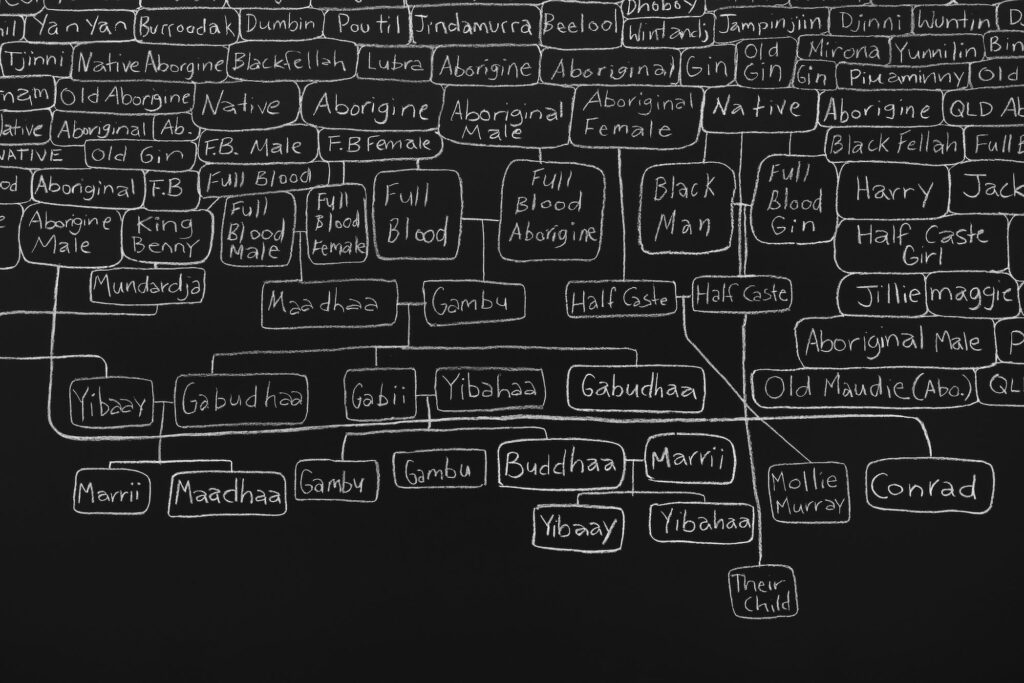

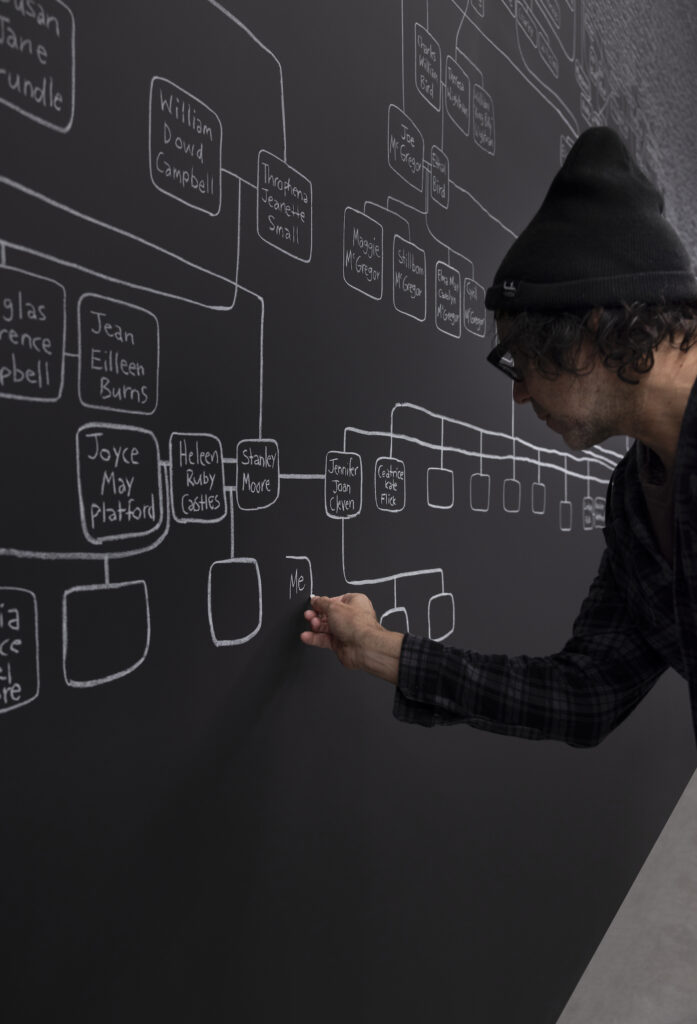

It is with this humility that kith and kin, meaning ‘friends and family,’ has become one of the most monumental and unifying exhibitions by a contemporary Australian artist to date. Using a fragile stick of chalk, notably a tool associated with learning, Moore painstakingly hand-drew 65,000 years of his family heritage onto the pavilion’s blackened walls. This physical task took the artist two months, not to mention the enormous effort and time he invested in tracing his lineage, which, like much Indigenous history, has been lost to colonisation or is buried deep within archives. Despite the tremendous volume of Archie’s research, its marking in a powdery, impermanent material references the instability of this history, seemingly able to be wiped away without a trace.

Attempting to follow its branches, the family tree grows and expands with an almost autonomous determination. Latching onto a name—‘Peggy’—I found my eyesight dancing up and across walls. Tracing, tracking, searching: she must have been the daughter of ‘son of Maria,’ who was related to ‘Dindin’ . . . and he was fathered by ‘Billy,’ who has ties to ‘Policeman Jimmy’? Names arch around fire exits, peek from the lip of door frames, and creep up and across the ceiling. I found myself consumed by this search, until names overlapped and blurred, and my neck craned so far back that I had to seek another entry point. This heritage, which fills the periphery of the pavilion, gazes down upon a shallow pool of water holding a platform of dense, neat stacks of redacted documents. Without the immediate knowledge of what these documents contain, the solemnly floating platform, sitting above silent, still water gives the guttural impression of a memorial—an island of loss.

Similar to the family tree, where names stretch beyond the viewer’s discernible eyesight, these documents are deliberately positioned at a distance, rendering their contents unreadable. This architectural choice can be interpreted, in part, as a metaphor for Australia’s geographical isolation from the rest of the world. Our island nation’s watery boundaries hold us afar. While viewers may find themselves confused by futile attempts to decipher the papers’ contents, this hints at the enduring frustration experienced by Indigenous peoples who have been forcibly distanced from so much of their cultural knowledge.

Among these papers are coroner reports detailing 557 Aboriginal deaths in custody since 1991, a number that includes individuals from Archie’s own family. “We are 3.8% of the population, but 33% of the prison population,” Archie solemnly remarks. In stark contrast to the unified, chalked genealogy, this massive white platform bears only a fraction of the weight of our nation’s brutalities against its Indigenous peoples. These individuals, who once had lives, families, responsibilities, and futures, are at times reduced to numbers in the pages of these silent stacks. Archie unpicks this anonymisation by allowing the water that surrounds the work to reflect his family tree. Faintly catching the white markings of names, the essence of personhood is reclaimed in a whisper.

Working with “250 years’ of written records since colonisation,” Ellie reflects on how this research highlights both the limits and potential of the archive. In her words: “it possesses a reparative, speculative element that addresses the fact that Archie’s family, along with many Indigenous peoples, are largely disconnected from their oral histories.” In the face of immense loss, Archie looks to research as a means of resurfacing Indigenous histories and invites us into the immense process of piecing together what remains of the past for the sake of our future. Here, the significance of the archive in shaping our present is underscored. Our history forms our future, and Archie’s tenacity in research, coupled with his vulnerable presentation of it, resoundingly declares: if we accept it without revision, it will continue to dictate our lived reality.

Drawing from Indigenous kinship systems, where one might have multiple mothers, fathers, or totemic connections to the natural world and beyond, this framework of understanding family ties fosters an expansive sense of care. It weaves us into the fabric of every living organism on this planet, and with that, comes a shared responsibility. Archie further signals this ethos by leaving a small, rectangular window open to the space. Placed low at ground level, this aperture permits a fragment of soft, natural light to wash onto the concrete floor. Within the dimmed exhibition space, which elicits the celestial gravity of ancestors, this glimpse of the outside served as a gentle reminder of the natural world beneath my feet. I found myself momentarily absorbing it as a reprieve from the density of my surroundings, only to watch the watery murmur of the green-grey canal below. Archie characterises this choice as a means of enabling viewers to “glimpse the canal outside, which flows to the Venetian Lagoon, then to the Adriatic Sea, and onward to the rest of the world, eventually reaching the continent of Australia, showing its eventual connection to everything around it.”

Lyrical, moving, and vital, the exhibition pulses within you like your very own heartbeat. Archie reaches out to his audience, extending himself through the boundless tapestry of his heritage to remind us of our universal truth: we are all connected. If we trace back far enough, we find a common ancestor. From every encounter, birth, bloodline, pilgrimage, conflict, cultural fusion, and societal transformation, our genealogies inevitably intertwine. It is a fundamental reminder, one that urges us to consider our obligation to care for and nurture all that exists around us. This response, rather than being reductive, emphatic, or complicated, is both essential and simple. Here, you become both a solitary speck in an endless night sky and a vital part of an expansive familial collective, as someone’s neighbour, daughter, son, lover, friend, kith, or kin.

I’ve yet to encounter anyone from Australia’s art scene who hasn’t been profoundly moved by the pavilion’s monumental achievement. This undeniable success and widespread acclaim further affirms that the open “expression of interest” process used to select participants, now in its third year of use, is indeed the path forward. Within the Brisbane arts community, Archie and Ellie are cherished. Their legacy is marked by an unwavering dedication to the creative industry, a commitment that has come full circle as the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art has announced an iteration of kith and kin, will return to Brisbane. For both Archie and Ellie, alongside Creative Australia, it’s evident that bringing this exhibition home, allowing it to thrive locally, was an essential inclusion.

I doubt many of us will forget when the pavilion was announced as the recipient of the Golden Lion. The collective pride we felt was tangible. Social media and news outlets flooded with praise and a shared sense of triumph. Amidst the backdrop of local gallery space’s teetering on the brink of closure, the divisive residue of the referendum, and a sense of stagnation within the creative sector, this moment feels both unifying and hopeful. Jose Da Silva, Director of UNSW Galleries and curator of the 2024 Adelaide Biennial, captured this sentiment in a post shortly after the award announcement, and I find it fitting to conclude with his words: “I can’t imagine a more perfect moment for contemporary Australian art.”

Taylor Hall is a curator, arts writer and project manager from Brisbane (Meanjin), Australia, now residing in London, UK. Following writing and curatorial projects with L’oeil de la photographie, Redland Art Gallery, Outer Space, University of Queensland Art Museum, Metro Arts, Onespace Gallery, and Vacant Assembly, she was selected as a participant in the 5th Edition of the Autumn School of Curating held in Romania. Taylor acts as the Business Manager for the acclaimed London Architecture firm Lynch Architects and their affiliated publishing house, Canalside Press.