Walking up the stairs and into Andrew Arnaoutopoulos’ exhibition at Fireworks Gallery, I was struck by a series of bright ultramarine and off-white paintings mounted so as to gently touch and riff off one another. I’ve seen a couple of these blue paintings of recent times. They are strong as individual works, yet presented like this, they’re compelling in a new way—and they’ve not been shown publicly before.

Titled Samos blue cluster, there’s an immediate affinity with the island of Arnaoutopoulos’ birth, an island I’ve often heard him speak of with love and eloquence. The ‘cluster’ of 16 paintings are grouped horizontally and in such a way as to echo the shape of Samos itself in a loose pixilated version.

While the exhibition’s title, Eternity, takes its name from a single painting with that word inscribed diagonally across its speckled, rust-like surface, the Samos blue paintings are the centerpiece of the exhibition. There’s an unmistakable feeling of the Mediterranean or the Aegean in the vibrant hues, but the colours—predominant blues and off-whites with fleeting touches of rust-red—are taken from memories of the faded walls of an abandoned leprosy hospital on Samos, last visited by the artist in 2016. Given the hospital’s location on an Aegean pebble-beach, Arnaoutopoulos says it’s also fine to conceive of the more direct azure-blue-sea link.

These themes are no surprise. Arnaoutopoulos was born and lived on Samos until the age of nine, in 1954, when he and his family sailed on the migrant ship Fairsky to Sydney and on to Brisbane where he’s since lived and worked. A not unfamiliar Greek-Aussie story. The family rented in Highgate Hill before settling in West End with the young Andrew attending South Brisbane primary school (now State High). While his parents were Greek Orthodox, on occasion they went to West End’s Greek Evangelical Church, whereI still hear bright songs coming from the old place as I walk home on Boundary.

He tells me that he worked in fruit shops in the Gabba, for a sign-writer in Stafford, and then for Gadsden’s carton-packaging company. (There’s a connection here to a work in this exhibition, Trojan horse installation, assembled from a series of printed cardboard boxes.) About this time, in his late teens, he started painting, always in acrylic (because he liked it), later taking lessons from well-known artist Roy Churcher. This is how his career began and it’s as if he always knew what he was going to do.

At the time Arnaoutopoulos began painting you could count the number of Greek-Australian artists on one hand. Now, after a four-decade practice, a considerable number of other Greek-Australian artists have joined him.

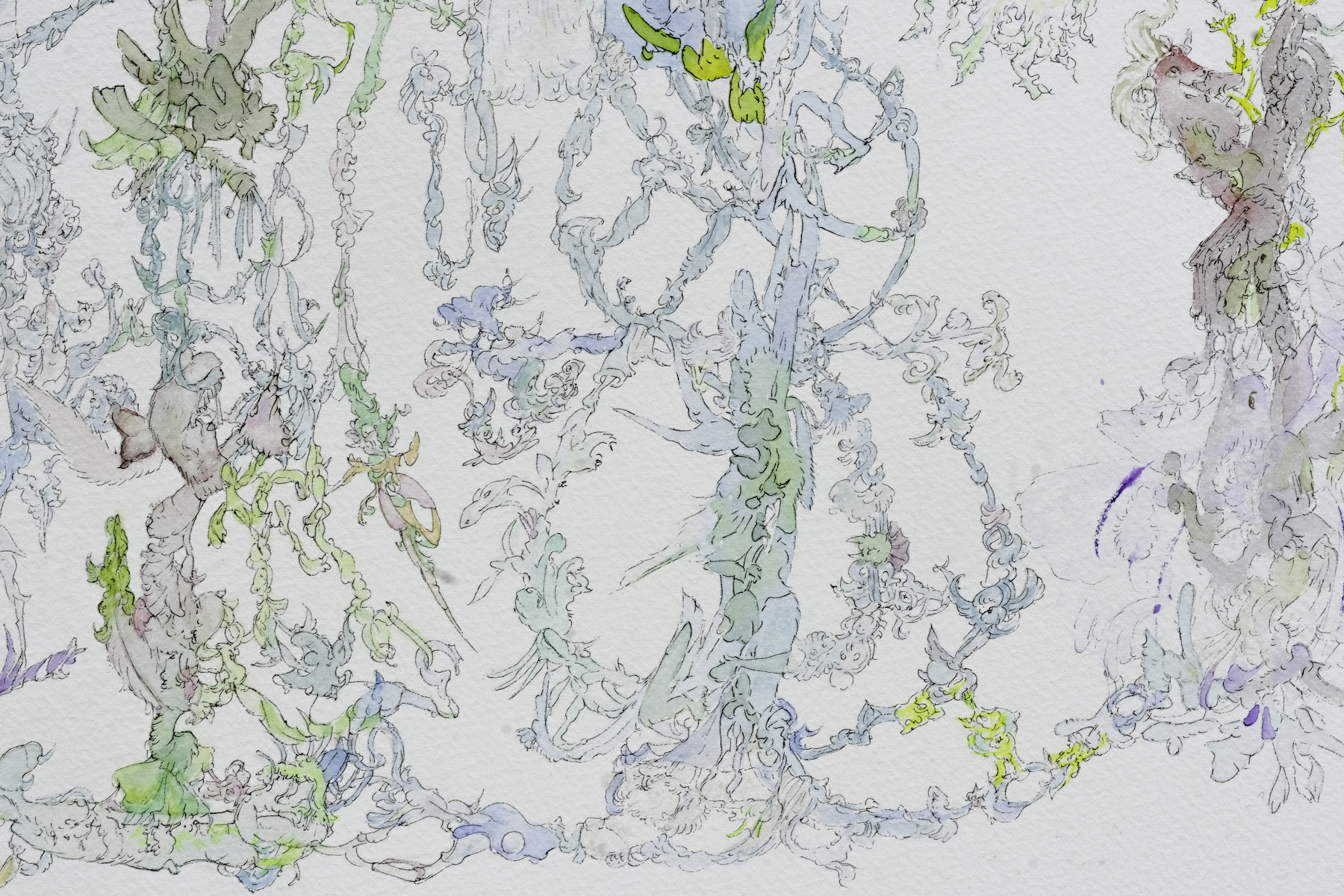

Arnaoutopoulos and curator Nicholas Tsoutas have collaborated to reconfigure a considerable number of individual paintings and re-present them in close-hung groups or clusters. There are four distinct but related clusters selected from four different series of canvases: Samos blue cluster (the largest), abstraction grey (six panels), abstraction yellow (seven panels), and abstraction markings cluster (seven panels). Tsoutas says that 90% of the paintings have not been previously shown; in fact, the Samos, grey, and yellow groups were all created during periods of Covid isolation.

All of the canvases are abstract. That is they are strictly non-pictorial, even though one series, abstraction markings cluster, closely resembles rusted steel sheeting heightened with minimal flashes of bright colour.

Tsoutas, who’s worked closely with Arnaoutopoulos on several projects, explains it like this: “The critical power of Arnaoutopoulos’s abstract paintings lies precisely in the almost unconscious, poetic minimalist aesthetic that he imposes on his canvas, blurring the distinctions between what constitutes a painting as a finished work of art and the by-product detritus that the painting process produces’. Regarding the industrial surfaces and bi-product aspects of the works, Arnaoutopoulos says: “my reality is that the factory is no longer the motivation or reference . . . my factory will be in my studio.”

It makes sense when Arnaoutopoulos mentions his early influences, including two of the greats of American abstraction—Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock—as well as two renowned painters and mixed-media artists that followed, Robert Rauchenberg and long-term friend Jasper Johns.

Contrary to artists who may follow fashion, for 40 years or more Arnaoutopoulos has been working on a focussed line of painting exploration almost as a spiritual journey; a sustained inquiry, the intensity of which is still rare. In this investigation, issues of Greek heritage run in tandem with contemporary practice. He’s committed, for example, to the restoration of the Parthenon and the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles, the subject of which was the impetus for the Trojan horse installation, a political project proposed to the British Museum and rejected by them, of course.

Andrew Arnaoutopoulos walks a fine line between the cultural aesthetics of identity politics and the critical practice of a modernist trajectory of contemporary art. It’s refreshing to spend time with an artist who’s both unassuming and unpretentious—as well as a fine exponent of traditional Greek dance.

Ian Were writes on contemporary art, design, and culture and has recently written short stories. Since 1997 he has edited more than 20 art books and publications, including 12 books as a freelance editor.