I sat down to write a sensible review of Desire is a Machine. I really did. But halfway through my notes, somewhere around ‘Body without organs = Britney Spears??’ I realised that to make sense of the IMA’s latest delirium would be to betray it.

The show, with its layout of dead-end corridors and curtained passages resists any attempt at laying out an easily decodable linear narrative because that’s precisely its point: that desire is machinic, incoherently connective, but always profoundly productive.

French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari are the poster-boys of Stephanie Berlangierie’s curatorial rationale. For those who didn’t major in Deleuzian metaphysics, here’s your crash course: what if we imagined desire not defined by lack, but production, a flowing system of connections between “partial objects,” never resolved, and always generative. Thus, the show’s title: Desire is a Machine.

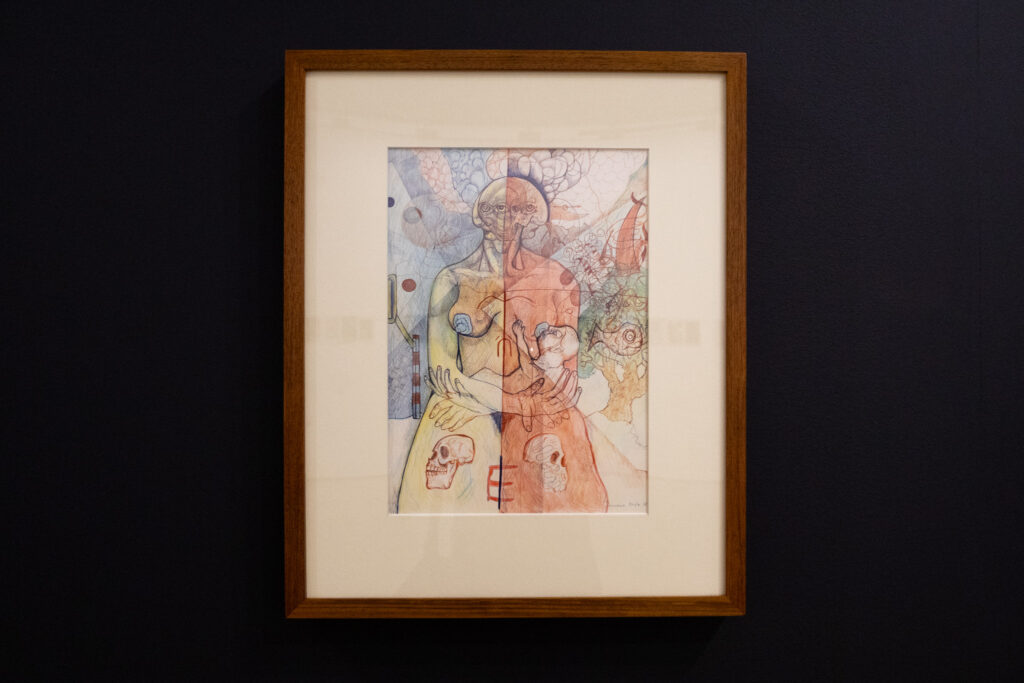

The IMA’s default white cube format, with its cool overheads and pristine white walls takes on a uniquely clinical feel in gallery 3 where the show begins. Seemingly out of place in this antiseptic landscape, we find the late Graeme Doyle’s feverish Untitled Drawings (c. 1978) scrawled in ballpoint pen and coloured pencil on paper. The didactic’s first line is quick to point out that the artist lived with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder since the age of eighteen. Given this context, the scrawled bodily fragments, gory shading, and strange religious iconography pulses with a familiar ‘outsider-art’ charge: raw, jagged, and disarmingly honest.

The label ‘outsider art’ branded by Jean Dubuffet in the 1940s, has always thrived on this myth of pure, uncivilised creation. It is art that seduces precisely because it seems to come to us unalloyed by the superego’s heavy hand. The curatorial choice to include Doyle’s works felt tinged with unease: a problematic promise that Doyle’s drawing might give us a peek behind the curtain of civilisation into something more ‘real’. The shows declared methodology – schizoanalysis – works precisely by rejecting the chaise lounge of neat diagnoses. So, does framing Untitled Drawings within institutional walls actually free or confine them?

There has always been a file of art’s voyeurs queuing for a glimpse at suffering wrapped up in aesthetic justification. Unfortunately, Desire is a Machine is no different. The flirtation with outsider art seems to neatly frame Doyle’s sketches as exoticized artefacts sanitised for consumption and offered up on diagnostic display. There’s a fine line between solidarity and trauma-touristic spectacle, and it’s not so clear which side we’re on. Desire, here, hums along ambiguously, raising the uncomfortable question: whose desires does Doyle’s work ultimately feed?

For this exhibition, the IMA is swaddled in curtains tinged with that sickly, hospital-green hue. They lead us down a dim corridor where we stumble first upon the Ueinzz theatre company’s fever-dreamish video works, and then emerging into the glare of Stuart Ringholt’s Yoga Art (2001/25): a sprawling avalanche of detritus that pours across the gallery floor. This staging is an effective touch, an on-brand world building that suggests the curtains are placed to shield us from something uncontainable, preventing an unruly and messy subconscious from leaking into view. Ringholt’s assemblage attempts to materially map meaning across a time of personal crisis when the artist was hospitalised for psychosis. His work crystallises the delirious, productive excess Deleuze and Guattari describe, seemingly spilling out from Doyle’s more intimate sketches into three-dimensional spectacle.

The exhibition hits a playful dead end with Giselle Stanborough’s installation, …Take My Hand, Give Me a Sign (2025). Triggered by a sensor plunging the room into darkness, erratic smears of glow-in-the-dark pigment flicker under UV light: spectral and faintly ridiculous. Scattered sketches of Britney Spears and scrawled, barely legible texts dissolve pop spectacle and theory into lurid absurdity. This room reads perhaps as the exhibition’s very own Deleuzian Body without Organs: Britney as media puppet, rebel, victim, and meme-machine; a hyper-flexible image made to satisfy every algorithmic desire. Stanborough’s deliberate resistance of aesthetic or narrative coherence in this pop-theory mashup perhaps highlights the conceptual slipperiness of Deleuze and Guattari: if the body without organs can be anything – even Britney Spears – it risks becoming nothing at all. An empty, glowing metaphor, neon slop spilling through conceptual fingers and onto gallery walls, everywhere and nowhere at once.

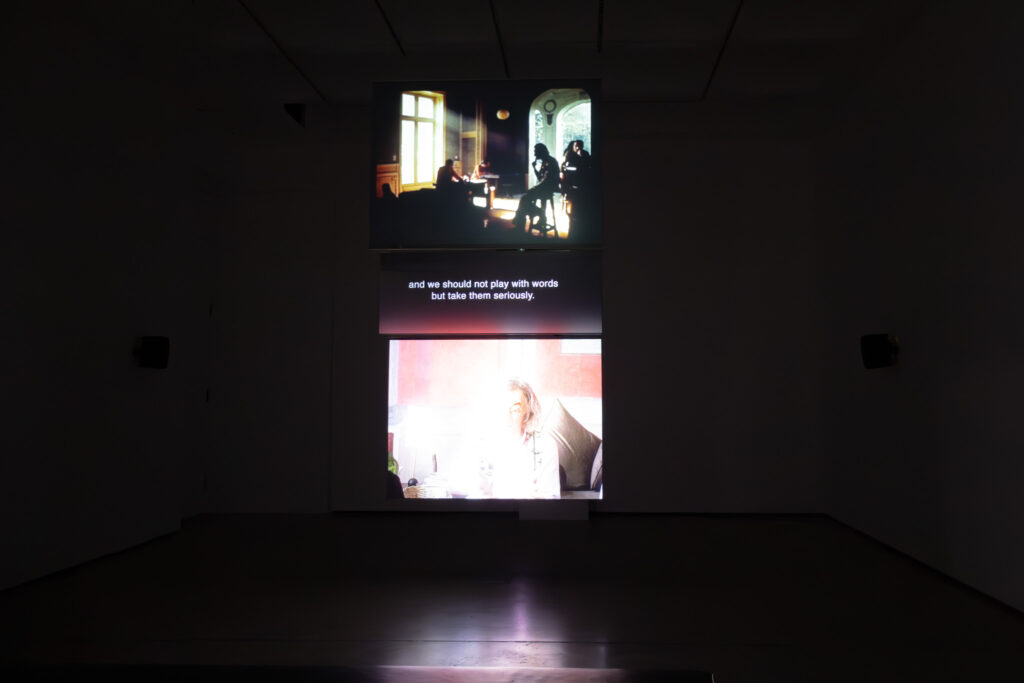

After the erratic spatial sprawl of Desire is a Machine, where Aurelien Froment’s Index of Coincidences (2025) march us in loops, the sound of Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato’s three channel video essay Assemblages (2010) coaxes us to consider the institutional promises of schizoanalysis. Melitopoulos and Lazzarato venture beyond the Western human-as-conqueror model into animist, micro-political, and decolonising subjectivities that refuse neat separations of mind, matter, human, and animal. Here, I recall cultural theorist Catherine Liu’s observation that under our contemporary capitalist condition, trauma is universal – and perhaps mental illness is the sanest response available to our global state of affairs. Ironically, when breakdown becomes normative, the clinic itself resists redundancy. This video essay matters because it insists on an actual exit: a vision of care and subjectivity beyond diagnosis, breaking Western binaries and psychiatric neatness yet remaining grounded by theory as is spelled out for us in the middle screen. With the installation’s tidy corridor of speakers and single inviting chair, the work becomes a welcomed and much needed didactic; a crisp, authoritative anchor to the show’s conceptual premise. ‘Sit down, class, here’s how theory might actually help you.’

Assemblages left me departing with a nagging critique: can schizoanalysis actually effect change, or has it devolved into mere aesthetic spectacle, a chic vocabulary of fragmentation deployed as the world quietly burns? Desire is a Machine flirts with this danger, romanticising fragmentation, turning trauma into luminous spectacle, and wraps the machinery of capital in poetic metaphors while the material conditions remain intact. But perhaps that’s the point: an honest mirror of our present: connecting, consuming, exhausted. It offers no exit because there isn’t one. Desire loops endlessly, plugging into the next thing. In the end, the true schizoanalytic figure is the visitor, wandering the white cube, waiting for an oracle that never speaks.

Desire is a machine, yes. But like most machines in the age of late capitalism, it probably just needs to be turned off and on again.

Holly Eddington is an independent curator, arts writer, and artist-adjacent on a good day. She lives between the gallery floor and the footnote, currently undertaking studies in advanced humanities and working as a gallery assistant in Magandjin. Holly is on Instagram @holly3ddington