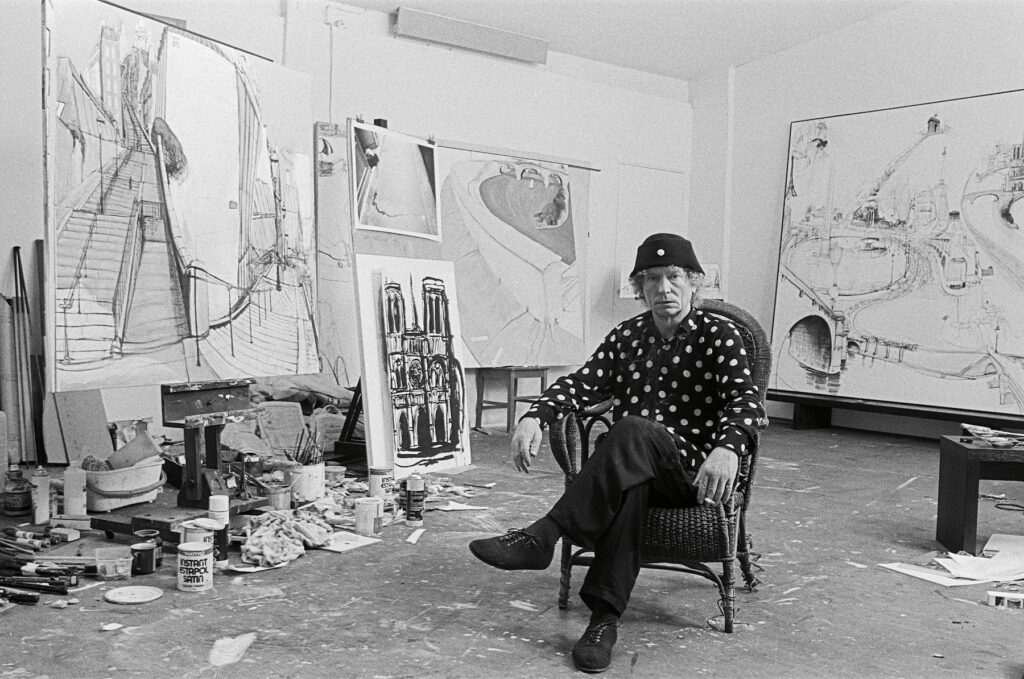

Three posters advertising Brett Whiteley: Inside the Studio hang on the façade of Logan Art Gallery. Appearing in the middle is a photograph of the artist himself, sitting in his studio. Reproductions of his paintings flank either side. If these introduce us to the exhibition in obvious ways: reiterating Whiteley’s command of colour (to the left), brilliant draftsmanship (to the right), and quintessentially studio-based-practice (in the middle) – layering masculinity, the hand of the artist, late Modernism, and Australian surfer culture meets bad-boy genius – they also foreshadow less explicit throughlines: the entanglements of art and artist and the tyranny of distance, both summarised in the impossible promise to take us behind the scenes, into the artist’s studio, four decades too late.

Slipping right and into one of Logan’s smaller exhibiting spaces, you will find photographs, sketches, paintings, drawings, and a worn leather boot fashioned into the likeness of an owl. This excerpt introduces the exhibition’s array of media and organising principle: neither rigidly chronological nor thematic, instead animating conversations amidst multiple works.

The photograph of Whiteley seen outside also recurs in this space across the full height and width of a modestly-sized gallery wall. Cigarette in hand and paint splatter at this feet, Whiteley appears drawn. His deeply etched wrinkles suggest a life lived too hard. Reproduced on the gallery wall, Whiteley is life-sized, as though the photograph stages an encounter between us and him, with the artist strangely out of place and time.

Heightening the oddness of the photograph: standing in front of Whiteley it becomes clear that he does not meet our (nor the camera’s) gaze, but instead looks past our right shoulder. Turning to follow his line of sight in the gallery, you see The 15 great dog pisses of Paris (1989), which also sits propped on a stool—in the photograph—behind Whiteley’s right shoulder. This curatorial device of recreating the studio by restaging its contents (now professionally framed, placed behind protective glass, and hung on the white walls of a regional gallery), which repeats in the following rooms, serves to place us, conceptually, in the same location as Whiteley: inside the studio. More tangentially, it highlights the paradoxical difference between photography and painting (and in turn, artist and artwork). Whereas the historicising black-and-white photograph of Whiteley underlines his removed existence there (in the past) and there (in Sydney); the painting is close enough to touch, existing both here (in the present) and here (in the room).

The painting in question captures a view of the Seine: its esplanade and stone arch bridge in warm and creamy tones. It features the commanding line of Modernism’s greats who saw compositional beauty in Paris’ industrialised landscape. Yet Whiteley adds Pollock-esque, tea-coloured splatters of piss to the scene’s parapet. Looking from this work to a nearby pairing of four Parisian street photographs, Whiteley’s concentration on similar traces of urine comes into focus. I can’t help but hear my mother’s withering assessment: “charming.” Distance repeats here as a kind of anguish, and insolent swipe, at Whiteley’s isolation from Paris’ golden era, when figures like Picasso, Matisse and Ernst (so present in Whiteley’s work) frequented the city.

The following room opens up to nudes, still lifes, and landscapes, continuing to make an argument for Whiteley’s exquisite drawn line. Exaggerated, sweeping, smooth and stretched; languid, liquid, bulbous and charmingly disfigured, in this room Whiteley’s line carries seductively across painting, drawings, and sculptures. An especially captivating view from the entry point to the room reveals the same lounging nudge across three of Whiteley’s works: a working drawing to the left, a painting on the far wall, and a sketch of the artist’s studio—including a sketch of said painting—on the near wall. A dialogue between studio and gallery, artist and artwork, past and present unfurls from this sketch of the studio into the surrounding space, which also brings to life from the drawing Pelicans in bronze, nude forms in hewn timber, and a lively painting of a palm paired with an erotic vase.

This central space also features the two most prominent works of the exhibition. Across their epic, history-painting-sized canvases, The balcony 2 (1975) and Self portrait in the studio (1976) share an intensity of ultramarine blue. The two views of Sydney Harbour and a studio interior also feature complex and shifting perspectives as well as leitmotifs of Whiteley’s practice: boats and palms, as well as reproductions of his oeuvre and visage. Of the two, The balcony 2 is less compelling. Despite its vitality, the work’s thick dashes of paint suggest a scrappiness and hark back to the thick texture of The 15 great dog pisses of Paris. By contrast, I could throw all of these words away and start this review afresh dedicated only to the latter.

Self portrait in the studio depicts a Lavendar Bay loungeroom also overlooking the harbour. Noticeably, the view seen from a window, the room’s wall, and the room’s floor all appear to exist in the one vertical plane. Objects within the room, however, occupy distinct planes. A small side table, for example, is firmly planted on the (non-existent) horizontal ground while a nearby glass table hovers somewhere between the expected floor and the elevated rug beneath its feet. This play with perspectival planes is a satisfying game between artists and critics, as we say: “I see what you did there.” Equally, I wonder if the two spotlights overhead, one on and one off, might reference the unevenly lit chandelier of van Eyck’s Anolfini Portrait (1434), no less because this painting also pictures a man and woman side by side.

In opposing corners at the bottom of the scene, a female nude—conjured via three sausage-like shapes and laid out on a daybed—stretches away from the artist’s hands. With the right, Whiteley begins a self-portrait on a canvas; with the left he holds a mirror wherein we see his finely detailed face. Notably, Whiteley grants to these two figures what he withholds from the other. Reiterating the active/passive, artist/muse gendered split of art history, he depicts himself with the doing hands and knowing gaze of an artist genius while his muse, given the fleshy torso and legs he misses, languises with neither arms, nor face, nor identity.

At this point in the exhibition, I wondered if Whiteley’s preponderance of sensual, sexualised, and anonymous female nudes might resurface, elsewhere, as a fear of women. Shark (female) (1965) and Shark (male) (1966), answer this thought. The twinned vertical sculptures, reminiscent of totem poles, stack round and concertined shapes of fibreglass, plaster, maplewood, chrome, and copper into the highly abstracted forms of two sharks. Where the male creature stands on two sturdy legs and tapers into a phallic head incised with a small ring of teeth, the female form throws back her head to reveal countless sharp daggers. The image is evocative of vagina dentata and a masculine fear of castration. These are striking works, confirming Whiteley’s skill as a sculptor and the rich symbolism of this practice.

The charcoal, pencil, and ink drawing, New York 3 (1968) is an understated gem of the exhibition. In this work, Whiteley looks out to New York’s metropolis from a high rise window, shedding the god-like perspective of The balcony 2 in favour of an elevated yet nonetheless realistic viewpoint. Whiteley’s hands emerge from the bottom of the scene again, this time planting a small yet dynamic splatter of ink on the otherwise empty page of a sketchbook, creating a sketch within a sketch. Complicating the boundaries between these two illusory worlds, Whiteley’s ink splatter radiates, from beneath the sketchbook, in powerful lines across the scene. There’s a playful confidence in this work. It’s as though in this location, with this drawing device, Whiteley is freed of the heavy history of Paris and painting. Art and artist remain entwined yet the tyranny of distance drops, momentarily, away.

Brett Whiteley: Inside the Studio is filled with oddities and delights: objects attached to paintings, grotesquely thick still life paintings, less than convincing collages, and a difficult to decipher portrait of feminist trailblazer Carolee Schneemann hang amidst lyrical drawings, striking works of composition, and surprisingly proficient sculptures. All is tied together by the exhibition’s undeniably strong and engaging curation. What a coup for Logan Art Gallery. Seek out a quiet visit, look at the works over your shoulder, and find the photograph of Whiteley dancing, eyes closed, with joy.

Louise R Mayhew is an Australian Feminist Art Historian and the Founding Editor of Lemonade.