Anastasia Klose’s powerful and heartfelt exhibition—For thy sake I in love am grown—weaves together old and new modes of creative expression, and embraces three different media: drawing, video, and singing. Drawing and video have been central to Klose’s practice for many years. While performance has been key to her process as well, this exhibition, curated by Hamish Sawyer, is the first time Klose has employed singing as an aspect of her multifaceted artmaking. Klose introduces traditional art songs and operatic arias from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries by performing them in the gallery, surrounded by her drawings and video. This lends a sense of gravitas and purity of intent—not evident in her earlier work—to the exhibition.

The exhibition’s title is from a seventeenth century song by Henry Purcell, O Solitude. In the song, the singer expresses:

What content is mine

To see those trees, which have appear’d

From the nativity of time,

And which all ages have rever’d,

To look today as fresh and green

As when their beauties first were seen.[1]

For the singer, solitude is the vehicle for cherishing the natural world as a source of timeless, universal awe; beauty; and comfort. The singer falls in love with solitude because it is the antidote to the distractions that cut human connection to nature.

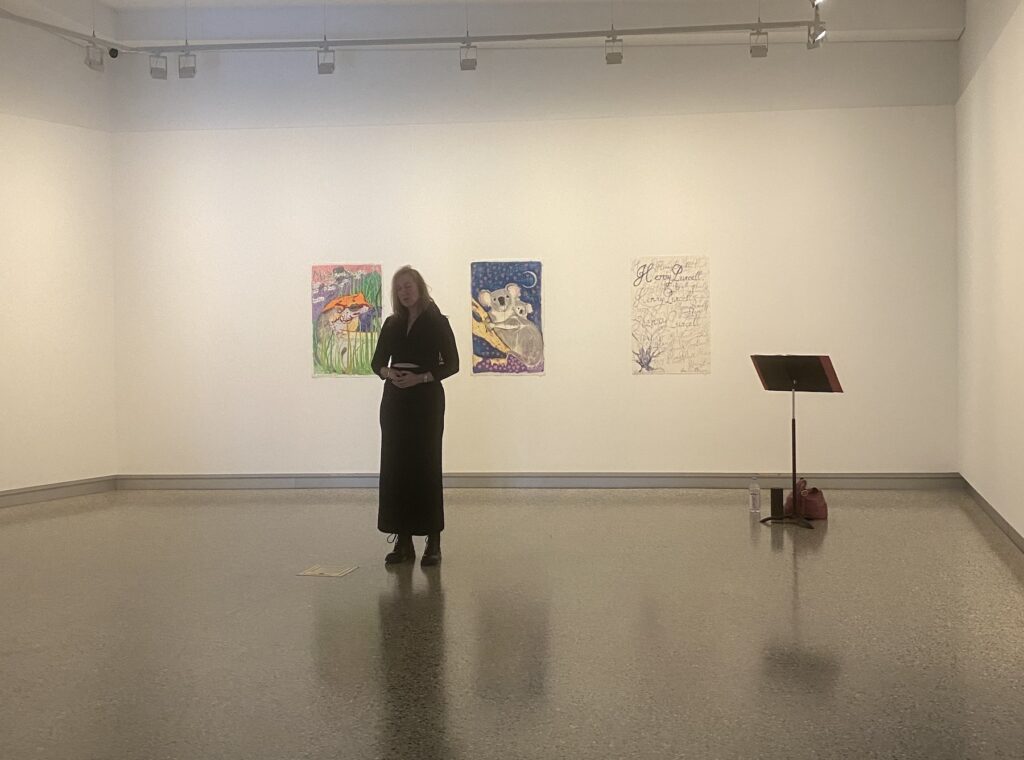

In the exhibition, Klose unites a love of solitude and nature with her love of animals, and gives voice to present-day environmental challenges in Far North Queensland (FNQ), where she lives. To hear O Solitude (a longtime staple of the classical song repertoire) performed by Klose, with her rich alto voice, surrounded by her contemporary portraits of endangered Australian species, is to listen to the song presented as a lament for all that’s been lost to human greed and disinterest in the survival of wild animals. Her performance revitalises an art form that many have considered to be waning for years and singing’s demanding techniques. By using her voice and older lyrical models of nature as activist tools for today’s environment, she initiates aesthetic discourse across temporalities, augmenting the formal and contextual possibilities for performance art while expanding the boundaries of her own practice.

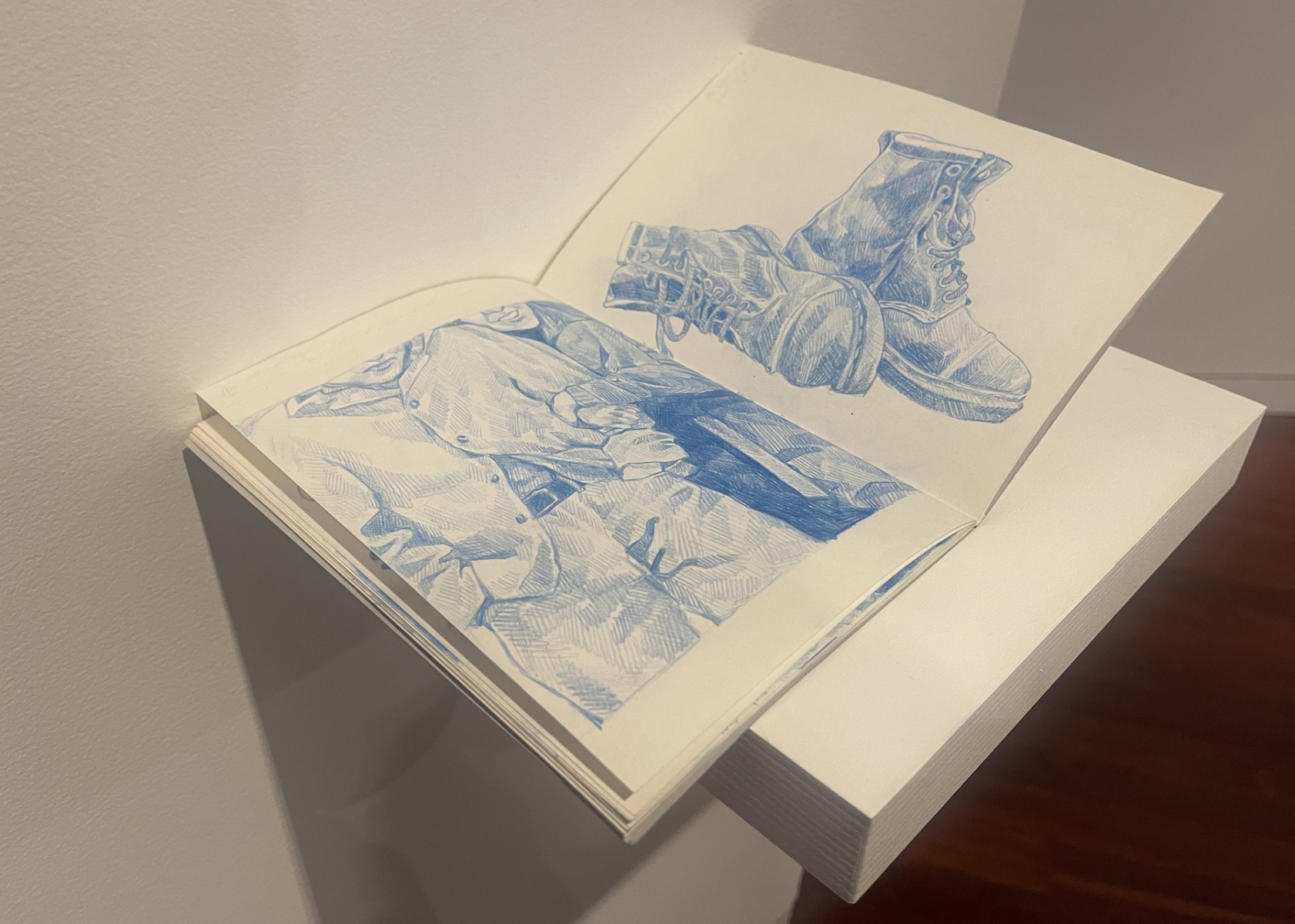

Klose’s portraits combine a lighthearted and exuberant application of pencil, ink, and pastel on paper in contrast with the solemnity of her songs. They present koalas, frogs, parrots, and a basset hound enveloped with decorative flourishes, cunningly astute abstract elements, curling vines, flowers, and love hearts. Klose is an adept colourist and well-versed in making intriguing compositional choices.

The basset hound is Farnsworth, Klose’s deceased and much-adored companion whom she credits with awakening her love for animals. In Self Portrait (2024), she draws Farnsworth in profile, with patches of textured blues, yellow ochre, grey, peach, and burnt sienna, calmly gazing out of the frame to his left. Surrounding him are garishly-hued flowers, hummingbirds, and clouds. The over-the-top flamboyance of Klose’s drawing style and colour choices recall her embrace of bad taste in previous works, such as In the Toilets with Ben (2005) (to which I’ll return below) to question social norms. Self-Portrait presents a blissfully naïve scene. Yet, we are also made aware of an acute sense of loss, not only of Klose’s canine companion, but also of a more childlike worldview, when nature seemed less threatened. This feeling of dispossession, accompanied by more than a hint of sorrow, extends from nature to the recounting of Klose’s break with the art world, which she scrawls in many colours:

I came to FNQ years ago because I thought it would get me away from the feeling of horrible dead end dread being in close proximity to the failed dead end culture of the art world and the way I totally gamed it by being obsessed with fashion and manipulation of just like [minded] people who didn’t have my balls to just offend.

At the bottom of the drawing, under the flowers and vines, she has signed the work in an Old English-looking hand, “ANASTASIA 2023.”

A viewer would be wrong to read as true or naïve Klose’s flashes of innocence. Using a childlike mode, she experiments with what is serious, embarrassing, or too uncomfortable to express. As a mature artist, she knowingly pushes herself to be vulnerable, to tap into and confess to her deepest feelings. In the exhibition as in Self Portrait, she plays with ‘girlish vulnerability,’ demonstrating a feminist recentering of marginalised knowledges (like that of teenagers) and asserting that diaristic, confessional, and autobiographical content can unearth real wisdom, truth, and love.

Klose’s work also acknowledges marginalised nonhuman beings as agential subjects. In Magnificent Brood Frog Holds a Picket Line with Poles to Fuck Off Invaders (2024), the frog is the hero of its own survival. In truth, this small, colourful amphibian is found only near Atherton, Queensland and is protected as endangered by federal law.[2]Tragically, the law is rarely enforced when companies move to clear pristine habitat.[3]

When Klose moved north to Mossman from Sydney several years ago, she joined the environmental conservation group, Rainforest Reserves. Her video work, For thy sake I in love am grown (2024), documents the group’s fight against a proposed Chalumbin wind-farm near Ravenshoe. It includes 1960s footage of white tourists delightedly holding and cuddling domesticated koalas. Klose contrasts these historical moments of nostalgic human-nonhuman interaction with contemporary, aerial shots of pristine forest habitat exploding into the air, clearing the way for roads and wind turbines. Subtitles throughout the video translate into English excerpts from Mozart’s Requiem in D Minor, which acts as a mournful and provocative soundtrack for the video. One subtitle beneath a violent explosion reads: “have mercy on us.” A viewer does not miss the artist’s intention: to call attention to the unjust trade of animal lives and ecologies for new energy solutions. Klose also includes moments of strain between the picketing Rainforest Reserves activists and wind farm employees trying to cross the line to get to work. These segments are authentic, anxiety-filled, and not easy to watch.

It’s important to consider Klose’s earlier, brazenly irreverent videos as foreshadowing the inbuilt courage of For thy sake I in love am grown. For example, In the Toilets with Ben is a video performance of Klose and an art school classmate having sex in a disabled toilet stall. Klose followed this with Mum and I watch in the toilet with Ben (2005), which was, indeed, documentation of mother and daughter awkwardly sitting together, watching Klose engaging in intercourse. In 2007, she produced Film for My Nanna. Here, Klose walks around the streets of Melbourne wearing a white wedding dress and a cardboard sign around her neck that read: “Nanna I Am Still Alone!” The descent into abjection of these earlier video performances problematised the boundaries of acceptable behaviour in the human search for love.

For thy sake I in love am grown expands its focus. Klose now bravely offers her work on behalf of other beings who have no means of self-protection. Her practice continues to engage with love’s place and power in the world; however now she harnesses her sense of injustice to address the breakdown of biodiverse humans and nonhumans entanglements that underlie our shared survival. While continuing to make art from a highly personal standpoint, Klose now confidently voices her love for nature and prompts us toward a path for redemption.

[1] O Solitude was composed by Henry Purcell in 1685, set to a poem by Girard de Saint-Amant (1594–1661) and translated by Katherine Philips (1631–1664).

[2] Frog ID.

[3] “Threatened Species Habitat Destruction Shows Federal Laws Are Broken,” UQ News, 9 September 2019.

Carol Schwarzman is a visual artist and arts writer based in Meanjin/Brisbane. She is currently a PhD candidate at University of Queensland.