Located on the south bank of the Maiwar/Brisbane River, upstream from the Port of Brisbane, is a military precinct. In 1881, Fort Lytton was built as a front line defence for the city, to safeguard the port from enemy attack. Although the port was never seriously threatened, the fortification, like many others along Australia’s east coast, was constructed as a show of British power and ownership. These defences were intended to address the anxieties of settlers who feared the expansion of other European powers active in the Pacific during the 19th century—like France, Russia and Germany—following the withdrawal of imperial garrisons in the 1860s.

Considered the birthplace of Queensland’s military history, the Fort was in use until the end of World War Two when it was decommissioned and left to fall into disrepair. In 1988, ownership transferred to the Queensland Government who declared it a heritage site and designated the surrounding land a national park.

When I arrived at the military precinct last month, I was unaware of the Fort’s existence, its military history, or its quarantine station. Perhaps this was, in part, because the site was built as a secret defense area and retains a furtive quality.

It was in search of the exhibition, A Narrow Strip Along a Steep Edge, curated by Holly Eddington, that I was introduced to these surroundings. Eddington explains that she was interested in exploring a site outside of the traditional gallery, and explains: “In this removed location, it felt like time and history stands still, allowing viewers to experience deep and meaningful looking.”

This is the second exhibition by the emerging curator, who recently curated Dithyramb, a group show held in the basement-level nightclub, Door84, located in Brisbane’s Queen Street Mall. Her curatorial practice shows a pattern of working outside ‘white cube’ spaces. This approach offers two key benefits. Firstly, it addresses a genuine lack of early-career opportunities for emerging curators in Meanjin/Brisbane—and in Australia more broadly—to gain experience and develop their own practice. By sourcing her own exhibition venues, Eddington bypasses the limitations and approval processes typically associated with artist-run initiatives (ARIs), commercial galleries, and institutional settings—especially the latter two, which are often extraordinarily hard to access. Secondly, stepping away from the sterile, ‘neutral’ environment of a conventional gallery—sometimes considered an ‘anti-museum’ act—provides an opportunity to respond to the social context and unique characteristics of a site. Fort Lytton offered this in spades.

Curious about what lay ahead, I walked from the carpark toward the river’s edge. I passed the old doctor’s quarters, boiler house, and disinfecting block; continued past the museum belonging to the Queensland Military Historical Society; across a moat; and eventually approached the nineteenth century pentagonal fortress. Inside its labyrinth of casemates and connecting passageways were works by eight local and interstate contemporary artists: Max Athans, Miguel Aquilizan, Ziyi Wei, Jessica Dorizac, Charlie Robert, Angel, Yanru Pan and Dean Ansell.

In the first casement (meaning a small room built within a fortress, sometimes designed with openings for firing guns or missiles), I encountered a work by Dean Ansell, a Meanjin-based artist of Melanesian (Riḡorabana and Balawaia, Papua Niugini), Maltese, and Anglo-Celtic descent. Rigirigi (2025) translates from Balawaian to mean ‘animal trap’ or ‘at the edge.’ I studied Ansell’s sculptural assemblage of mechanical parts and looped audio, and identified forms and objects that imbued the work with a sense of restraint and imprisonment. Fixed on a central pole was a rusted shackle connected to an iron ball and chain—the kind you typically imagine attached to a prisoner’s ankles. A steel wagon wheel rested precariously on an upright rock, ready to fall and entrap its next victim. At mid height, a small image of driftwood washed on a sandy shoreline extended from the sculpture, its visibility enhanced by the lens of a magnifying glass. This photograph was taken at Black Beach in Rigo, Central Province, Papua New Guinea, near the traditional lands of Ansell’s family. He explains that the driftwood is “at the edge” of the forest and the ocean where hunting and fishing takes place.

I took note of the various assembled pieces while indistinguishable sounds of dripping, banging, and aeolian whooshing reverberated around the otherwise empty and dilapidated space. The soundscape slowly dissolved as I moved out of the room, up a flight of stairs, through a narrow passageway, and onto the terreplein outside.

Before me stood a sculptural work by Charlie Robert, Plight (2025). It took two separate forms, both of which mimicked the architectural and operational qualities of the Fort. The sculptures were made of curved wooden sides held together with cylinder tubing. The wooden arches mirrored the curved doorways throughout the building, while the cylinders reminded me of bullets loaded into the chamber of a gun cylinder. The sculptures themselves were ambiguous, and their purpose unclear. They occupied the site like a defunct relic.

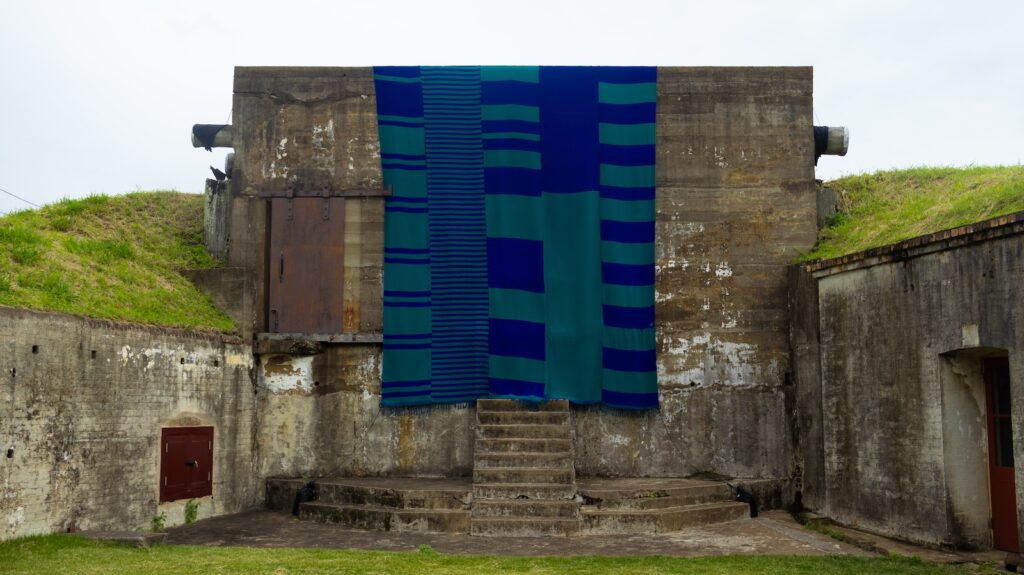

I looped back to the central courtyard, labelled on a map as the ‘parade ground,’ and spied Jessica Dorizac’s woven textile, Deep Waters (2025), suspended from a gun pit. Five vertical lengths of fabric with blue and green patterning were stitched together to form a large sail-like intervention, the bottom detailed with a fringed edge. Dorizac is a Filipino-Australian artist who lives and works between Laguna and Queensland. This tapestry shares a connection to the traditional handloom weaving practices of the Philippines. Dorizac, however, has used the bold geometric patterning of the textile to reference a radical camouflage strategy developed by Norman Wilkinson in 1917 called razzle camouflage (or ‘razzle dazzle.’) This aesthetic strategy was adopted by the UK and US Navies throughout World War One and Two with the purpose of obscuring enemy fire.

The scale of the work gave it a strong presence in the Fort’s courtyard, while, paradoxically, the green and blue tones lent themselves to the grassy terrain and Brisbane blue sky, enabling the work to blend into its surroundings. Deep Waters was suspended like a ghost ship, quiet yet resolute. This work may reflect the colonial power dynamics that riddle maritime histories, subtly gesturing to Western empires that drew upon the resources of their colonies to sustain engagements in war.

In another casemate, I found the work of Dorizac’s husband, Miguel Aquilizan, as well as Ziyi Wei and Max Athans. Aquilizan’s sculpture, In the Shallow Seas Unveiled (2025), is an assemblage of salvaged and repurposed materials. It takes on a skeletal form with its inclusion of a ribcage and skull. This bodily reference leans into the precinct’s quarantine history, which saw the establishment of a quarantine station between 1913 and 1914. Newly arrived persons considered to be at risk of carrying infection were taken to Lytton for fumigation and isolation. There were tight restrictions on where they could go and what personal belongings they were allowed to keep. Any clothing, linen, or other items suspected of carrying disease or pests was incinerated. The facility became particularly active during the 1919 outbreak of the Spanish Influenza when it housed personnel returning on troop ships at the end of World War One. Incredibly, the station remained in operation until the early 1980s when the government phased out human quarantine services.

Aquilizan’s art practice is rooted in his Filipino ethos of repurposing discarded objects. His sculptural works often interrogate social histories, particularly in relation to themes of migration, globalisation, and colonialism. In the context of Fort Lytton, his sculpture In the Shallow Seas Unveiled critiques the treatment of bodies within the former quarantine station. It often housed newly-arrived immigrants; their first experience of the country was from within the confines of a dehumanising facility. As such, the sculpture suggests a liminal space between human and nonhuman. It features three metal legs with wheels for feet, a phallic dolphin form protruding at waist height, a yellow heart studded with metal, a spinal cord constructed from tree branches and timber offcuts, and an assemblage of other materials fastened together with nails and cable ties.

In the corner of the room was a work by Narrm/Melbourne-based artist Ziyi Wei. Metal tubing extended from a concrete block, bending at the top in a right-angle. It supported a hanging metal sphere made of hundreds of silver petals, bells, and charms. A robotic mechanism made the sphere twitch and pulsate like a beating heart. When it moved, the bells and adornments chimed harmoniously. The result was enchanting and I was completely transfixed.

The other works in the room were made by Max Athans, the most recent (and final) recipient of the Jeremy Hynes Award. Polymerization I-VI (2023) consists of five grey and glossy resin relics fixed to a metal frame. They appear to be a mix of human and non-human skulls, presenting as curious anatomical statues. On the back wall was Nebuchadnezzar (2023), a digital print on leather featuring another strange anthropomorphic creature, kneeling on all fours. The material of the leather created an eerie skin-like texture over the body. The work is a reinterpretation of William Blake’s famous print Nebuchadnezzar (c.1795–1805), which portrays the King of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar II. According to the Old Testament Book of Daniel, Nebuchadnezzar was a legendary figure driven mad and forced to live as an animal due to his excessive pride. There was a connection between the works in this room and their explorations of the dichotomies of bodies.

Moving on to the final exhibition space, I found two canvas panels fixed to clear Perspex sheets and supported by a concrete base. This diptych, I Prayed for Lightning (2023), is a work by Narrm/Melbourne-based artist Yanru Pan. The panel on the left featured a face inside a car, dripping with glass-like beads, while the panel on the right depicted a mid-century chrome armchair on a shiny tiled floor. The imagery was rendered in shades of mint green, soft purples, and bright pinks. The tonal rendering, in conjunction with the images’ sharp lines and reflective surfaces, produced a clinical, dreamlike, and slightly jarring feeling. Pan uses luxury items—such as cars, furniture, and diamond-like tears—to signpost middle-class culture, highlighting how individuals use material possessions to build a fortress around their egos and themselves.

Behind these paintings, on either side of the wall, were two black inkblots laser cut from pieces of MDF. Their surface has been painted with bitumen rubber leaving a thick and sticky texture. Titled Threshold (2025), these works were made by recent QUT graduate Angel. Their skeletal-like cutouts are a nod to the 1920s Rorschach test, a popular test that uses ambiguous stimuli in the form of inkblot shapes to draw a response from the viewer, theoretically revealing internalised character traits, attitudes, and psychological states. The shape of the inkblots in this work map the flaking marks on the walls of the casemates, referencing the site’s physical decay. The reimaging of the Rorschach test also suggests a questioning of the Fort’s emotional state, which is an interesting thought.

In her curatorial statement, Eddington presents the show’s premise as exploring borders and liminality in relation to Fort Lytton. Eddington explains that by happenstance this expanded to include thresholds within the body, which is evident in works by Aquilizan, Wei, and Athan. This fascinating premise was particularly successful in works made for the exhibition, such as Dorizac’s Deep Waters, Ansell’s Rigirigi, and Aquilizan’s In the Shallow Seas Unveiled. Other works related loosely to the fortified and utilitarian aesthetic of the space, or the concept of a paradox more generally, but didn’t critically engage with or respond to the history or conditions of the Fort and surrounding precinct. Athans, Aquilizan, Dorizac, Robert, Angel, and Ansell indicate the emerging talent of the local art scene, actively exhibiting in ARIs and institutional galleries, while Wei and Pan give insight into the work of recent Melbourne art school graduates. Curated via a combined open call-out and one-on-one invitations, their selection reveals Eddington’s savvy for networking, building relationships, and identifying interesting undercurrents in the practices of artist’s on the rise. In all, A Narrow Strip Along a Steep Edge was ambitious, multifaceted and, undoubtedly, a standout show for 2025.

Gabrielle Bergman is an early-career curator, art historian and writer based in Meanjin / Brisbane. She is currently working as a Curatorial Assistant at the Museum of Brisbane.