Stepping into this exhibition feels like entering a psychedelic time capsule.

Enjoy This Trip: The Art of Music Posters offers a full-sensory flashback to a time when music and design reshaped culture. Drawn from the National Gallery of Australia’s extensive collection of Australian and international posters, the exhibition invites you to drift through the dreamy haze of the 60s, ride the graphic waves of the 70s, and hit the jagged edge of punk and protest into the 80s. Curated by Leanne Santoro, the exhibition offers nostalgia in high fidelity.

The exhibition’s roots trace back to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury in the mid-60s, a hotbed of counterculture where artists, musicians, and activists converged. As the ‘San Francisco Sound’ took off, so did a new visual form: the psychedelic music poster. Melting fonts, vibrating colours, and kaleidoscopic compositions became the calling card of a generation. Drawing on Art Nouveau, the Vienna Secession, Op Art, and Native American design, they transformed gig ads into art.

A cornerstone of the show is the National Gallery’s 1978 acquisition of 565 posters from Ben Friedman’s legendary Postermat store in San Francisco, an extraordinary archive capturing a radical moment in graphic design and cultural history. Touring this material, Enjoy This Trip brings us back to a pre-digital era, when art was physical, handmade, and meant to grab attention on street poles and shopfronts.

The exhibition moves through a loose chronology. Posters are arranged thematically by artist, aesthetic, or political moment, allowing viewers to track shifts in tone, technique, and subcultural style. Accompanying texts are clear and succinct, letting the posters speak loudest.

Though the visuals dominate, the show also rewards close attention to the hands-on processes behind them. Long before Photoshop or Canva, poster artists were technicians, inventors, and risk-takers. Two analogue techniques underpin much of the work on display: screenprinting and lithography.

Screenprinting, with its bold colour fields and high-contrast layering, was ideally suited to the energy of live music. Artists used mesh screens, stencils, and squeegees to push ink through exposed areas, building hallucinatory designs one colour at a time. It was fast, flexible, and affordable, and worked on everything from paper to T-shirts. With photo-stencils, they could combine hand-drawn and photographic elements into electrifying compositions that emulated the sounds they were advertising.

Lithography offered a gentler, more painterly finish. Artists drew with greasy crayons or liquid tusche directly onto stone or metal plates. Oily ink clung to the drawn areas while water repelled it elsewhere, producing fluid curves and delicate tonal shifts. It was a method that favoured subtlety and sinuous linework—perfect for the Art Nouveau influence running through many of these prints. Whether screenprinted or lithographed, the result is saturated with colour, texture, and intent.

In an age of Spotify drops and Instagram teasers, these works speak to a slower, grittier kind of music culture – one built through Xerox machines, street corners, and local scenes. They weren’t designed to be preserved. They were meant to be plastered, passed around, and seen.

Enjoy This Trip pays homage to the psychedelic vanguard, the so-called Big Five whose posters defined San Francisco’s visual identity: Rick Griffin, Alton Kelley, Stanley “Mouse” Miller, Victor Moscoso, and Wes Wilson. Each brought something distinct to the mix. Griffin’s style mixed mythic Americana with mysticism. Kelley and Mouse blended Art Nouveau flourishes with underground irreverence. Moscoso made colours vibrate with intensity.

Wes Wilson, credited with inventing the psychedelic font, twisted type into woozy abstraction, inspired by Viennese Secessionist lettering and his own acid-fuelled explorations. His posters were provocative, sensual, and confrontational. But as with many canons, there are omissions. The gender imbalance in the scene is striking, and only partly addressed by the inclusion of Bonnie MacLean. Her posters for the Fillmore brought gothic intensity and feminine presence to the genre. Other women artists (like Mari Tepper) get brief but welcome appearances.

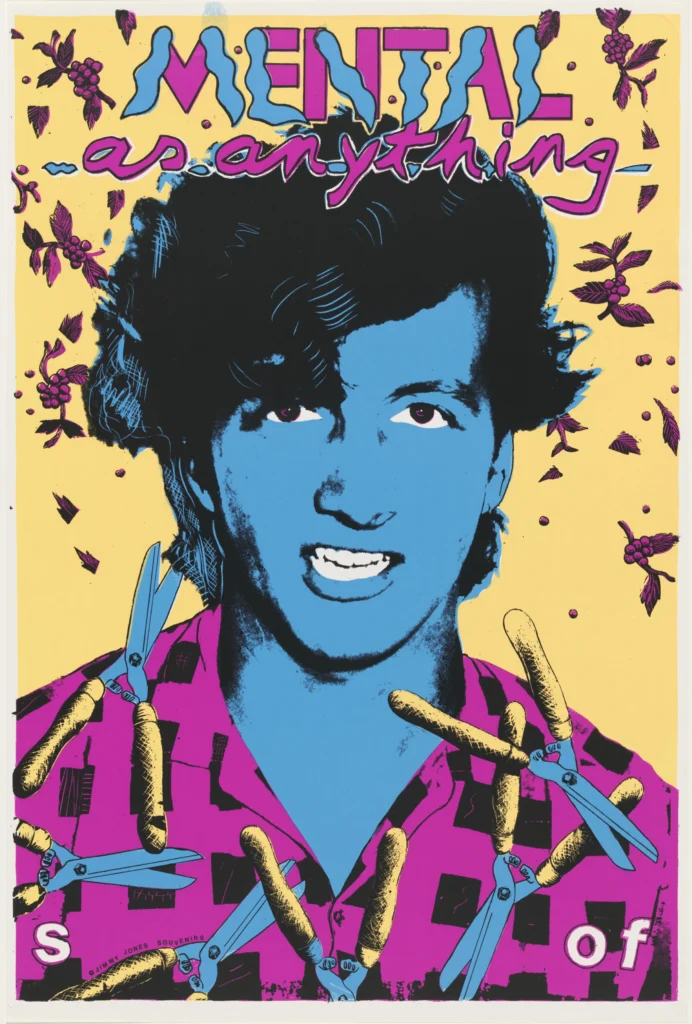

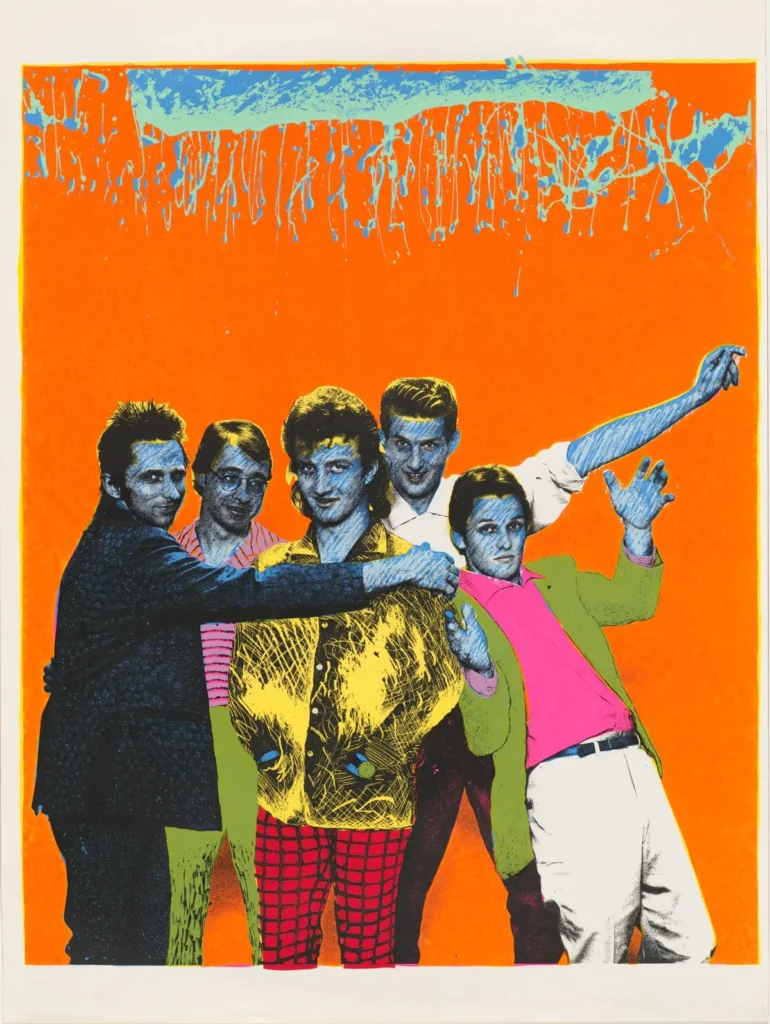

Similarly, the Australian works, though included, are mostly framed as regional variations rather than central voices. However, some break through. Paul Worstead, one of Australia’s most prolific poster artists, brings an irreverent, street-smart energy that stands apart from the San Francisco aesthetic. His posters (many made for Mental as Anything) draw on local culture, beach-town humour, and pub-rock cheekiness. They’re deliberately lo-fi and proudly unfancy, trading spiritual transcendence for slapstick and satire. Where the American artists borrowed from Arabic calligraphy and op art, Worstead riffs on garage bands, lino floors, and backyard rebellion.

Collectives like Earthworks and Lucifoil also shine, infusing poster design with protest and grassroots politics. These weren’t designed to be gallery pieces. They were tactical, ephemeral, and made to provoke. Blazing in red and yellow, Judi Keneally’s poster for Goanna’s Solid Rock (1982) hit hard, and was a reminder of how these posters connected music with resistance and identity, especially in an Australian context.

Where the San Francisco works shimmer with psychedelia, the Australian ones feel rawer, faster, funnier. More now. Less trip, more rip in—that is, energetic, local, and unpretentious.

As you exit Enjoy This Trip, the kaleidoscopic overload may linger, but so do the questions: Who gets remembered? What gets archived? What kind of design gets canonised, and why?

In an age of templates, filters, and AI-generated content, these posters beam with mischief and conviction. They capture the spirit of a hands-on era. And they prove that great graphic work leaves a mark not just on the wall, but on the collective memory.

Bianca Valentino is a writer and editor, she also publishes underground music magazine, Gimmie. She got her start making punk fanzines in the ‘90s and has written for national and international music, arts, and culture magazines for three decades. She’s a music fan, not a critic. Her debut book, Conversations with Punx, was released in 2024.