Conflated is a highly considered exhibition examining ideas of inhalation and breath. Conscious and unconscious patterns of breath take many shapes and rhythms. Indeed, breathing is a movement. Breath is not static. Highlighting this sense of breath, the works in Conflated use play—suggested by its use of vibrant colours, references to children’s activities, and participatory works—to explore the im/mobility of structures of breathing. Most compelling is how the exhibition—with these evocations of activity and form—also evokes experiences of comfort and discomfort.

David Cross’ inflatable beds, Pair (2021), initially encourage thoughts of parties and amusement because they are reminiscent of a small bouncy castle. However, the shape and symmetrical configuration of the beds alternatively incites respite and introspection.

Care and comfort are evident in Bronwyn Hack’s life-size hot-water-bottle-sculpture, Alfred (2021), which is encased in colourful and textural fabrics. Zoë Bastin similarly contemplates how we might nurture ourselves in Enough (2021). In the video performance, Bastin wears a cape of animal-printed balloons, encouraging empowerment and flight. However, the reality of the body’s gravity and heaviness sinks into the performance. A startling sculptural installation of the ‘cape’ effectively supports Bastin’s video. The sculpture is motion-activated, inflating and deflating as audiences walk past.

In further works, experiences of ease are turned on end. The transfixing collaborative video Omphalus (2021), by Amrita Hepi with Honey Long and Prue Stent, shows bodies morphing into and out of both themselves and a blow-up fluoro-green cylindrical object. The green tube is versatile and responds to the bodies’ movements, creating fleeting moments of hybrid bodily shapes. While these transient pictures are fascinating, Andy Butler’s performance Live to Your Potential (After Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog) (2018) dominates this space. His work disrupts the smoothness of Omphalus, with irritatingly twisting and crackling balloons. In the video, Butler consecutively makes duplicate balloon dogs. This mode of making, alongside his banal expression, displaces the balloon animals’ reference to children’s parties and games. Instead, his repetitive actions trace a predetermined purpose and outcome. By contrast, Omphalus‘ inflatable structures perpetually change into unexpected rhythms and forms.

More crackling sounds occur in the floating motions of Eugenia Lim’s jumpsuit installation Wearable Shelters (2022). The ingenious placement of this work alongside Live to Your Potential increases the experience of discomfort brought about via their out-of-sync tempos. Lim’s suits are suspended in a circle and tied hand to hand. The resulting form resembles the shape of the children’s game Ring-A-Ring-A-Rosy. In Lim’s subsequent video work, performers wearing the suits enact this same format and movement. However, the song’s dark undercurrents, the film’s workplace setting, and the performers’ deadpan expressions disturb a fun or comfortable atmosphere. There is a repetitive and fixed choreography in this work that is prosaic, like Butler’s performance. Here the workplace conditions indicate a mundane yet unsafe system. Safety concerns are further present in Christopher Langton’s installation, Breathe In Breath Out (2021), which presents a post-apocalyptic landscape. In contrast to the emphasis on physical activity in other works, Breathe In Breath Out is a static sculptural installation suggesting a future where the air is unsafe to breathe.

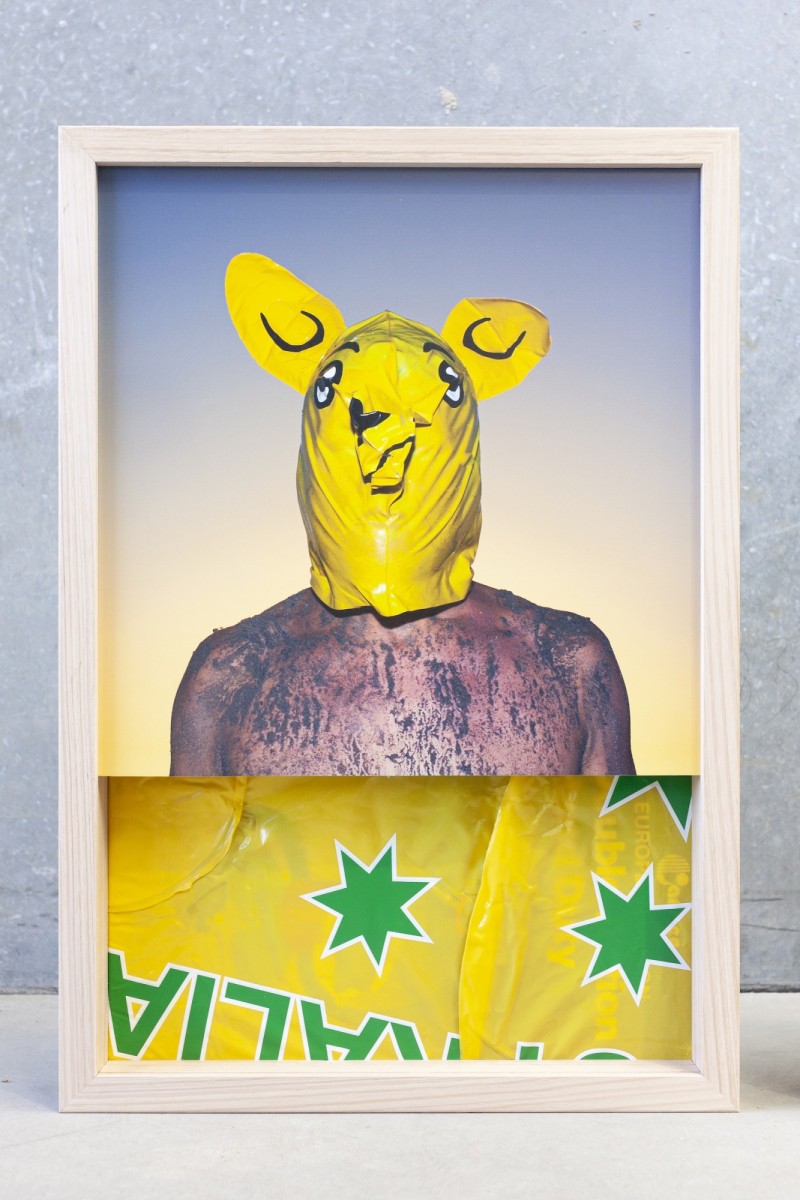

Steven Rhall’s photo triptych, Heretic Rituals (2020), is also still. In this work, Rhall wears an inflatable mask of a kangaroo mascot. The three photographs reveal a state of continued restriction as the mask changes from slightly inflated to vaguely twisted to almost fully encapsulating Rhall’s face. In the third and final image, the mask is tight across Rhall’s face and he can barely breathe. Beneath this photograph is a cut-out section of the mascot, including the two holes where you can inflate and deflate the mask. The two closed holes and deflated mascot invite me to let some air in. The confronting image and overall immobility of Heretic Rituals enhances this urge: making me consciously aware of their lack of breath and the importance of movement to living.

James Nguyen’s installation Inhaleinhaleinhale (2021) brings together moments of contentment and unrest. The work consists of a single chair with a light fixture suspended above. Like Pair and Enough, this is a participatory work. Once the viewer sits in the chair, a sound is activated. Sitting here, I am again uncomfortable, questioning if I am part of some experiment. More poignantly, I become aware of how calming or overwhelming ‘sitting’ can be. At this point in the exhibition I realised I was holding my breath. So I deeply inhaled and exhaled.

By activating fluctuations between comfort and discomfort, the works in Conflated expose the necessity for action and change. Breathing cycles serve as an intelligent framework for demonstrating this point. Whether consciously taking slow deep breaths or unconsciously breathing erratically, breath is a rhythm that shifts and blends with our surroundings. The operative effect that the exhibition triggers is that we can alter and play with our breath’s pulse: adapting pressured air pockets into permeable and pliable structures.

Conflated is a NETS Victoria touring exhibition curated by Zoë Bastin and Claire Watson. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government’s Visions of Australia program and the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria.

Sharna Barker is an early career artist and arts worker based in Brisbane/Meanjin. She is currently completing a Doctor of Visual Arts at Griffith University.