The jacarandas are still blooming in Toowoomba when I arrive to see the University of Southern Queensland’s Graduart 2024 show. Curated by Dr Rhi Johnson and Brodie Taylor across two exhibition spaces in the UniSQ Art Gallery and School of Creative Arts building, the graduating class’ studies have produced artworks in a wide array of media exploring diverse concepts. A graduate show always has an element of chance, the serendipity of a group of artists whose works happen to exist in concert. Yet several standout works in this cohort dovetail into three motifs on how we exist in time, space, and the body.

Jennifer Baker’s Elephant In The Room (2024) floats as a quilt of sewn tea bags, its umber hues due to rust from her family farm’s old gear as well as a nod to her grandmother’s love for a strong cuppa. Both this evocative piece and her other exhibited work, Mother’s Love (2024)—with hand-in-hand figures made from the farm’s barbed wire and soil—use her grandmother’s embroidery thread. This tying together of ancestral stories and materials conjures up the threads of fate, with Baker’s works knotting those timelines into the present.

Another complex telling of family history is Vanessa Thompson’s Hurtsville (2024), whose tableau of ceramic figures depicts four survival stories that are also recorded in a must-read booklet. The sculptures appear on plinths like a Nativity-esque parable, but Thompson’s tales are too real for fiction: lost in the bush, suffering war-borne PTSD, cradling an illegitimate child daringly brought home, slamming the fingers of a predator in a shower door. Thompson’s frank tour of the devastating situations she and her kin have faced shows how “stickability,” —as she puts it—or the irrepressible urge to survive our circumstances, can link us across time and through generations.

Connection to spaces, both natural and built, pure and polluted, is another motif featured in Graduart 2024. Peter Osborne and Johanna Park both deal with the relationships we form to our environments. Osborne’s tile work Overland (2024) and sculpture Trace I (2024) use glazes that are homemade with soil and minerals found near his Southern Darling Downs studio. The effect is a literal and emotional grit that elevates his earth-toned wares to an echo of nature’s sublime potential. Park’s stoneware Tableau II (2024) and ink work Continuity II (2024) look in the opposite direction, finding beauty in the familiar spaces of cities made by human hands. Despite their difference in medium, both find a throughline in an honest love for the everyday elements of architecture.

The Lost Archive (Vol. 1-11) (2023-2024) is a subtle piece by Gwen Walker with a similar adoration for built spaces. Visitors are encouraged to page through a collection of photo books that document her practice of “Artistic Wanderings” through Iceland and the UK. Her crochet work Blanket Made By Walking (Reykjavik) (2023) also chronicles her wanderings, with each stitch of multi-coloured wool recording what she calls an “intimate cartography of exploration.” Walker is not a photographer nor crochet artist by her own admission. If one must have a title, I’d say she is a flâneuse whose mementos of passage through space seek to inspire wanderlust.

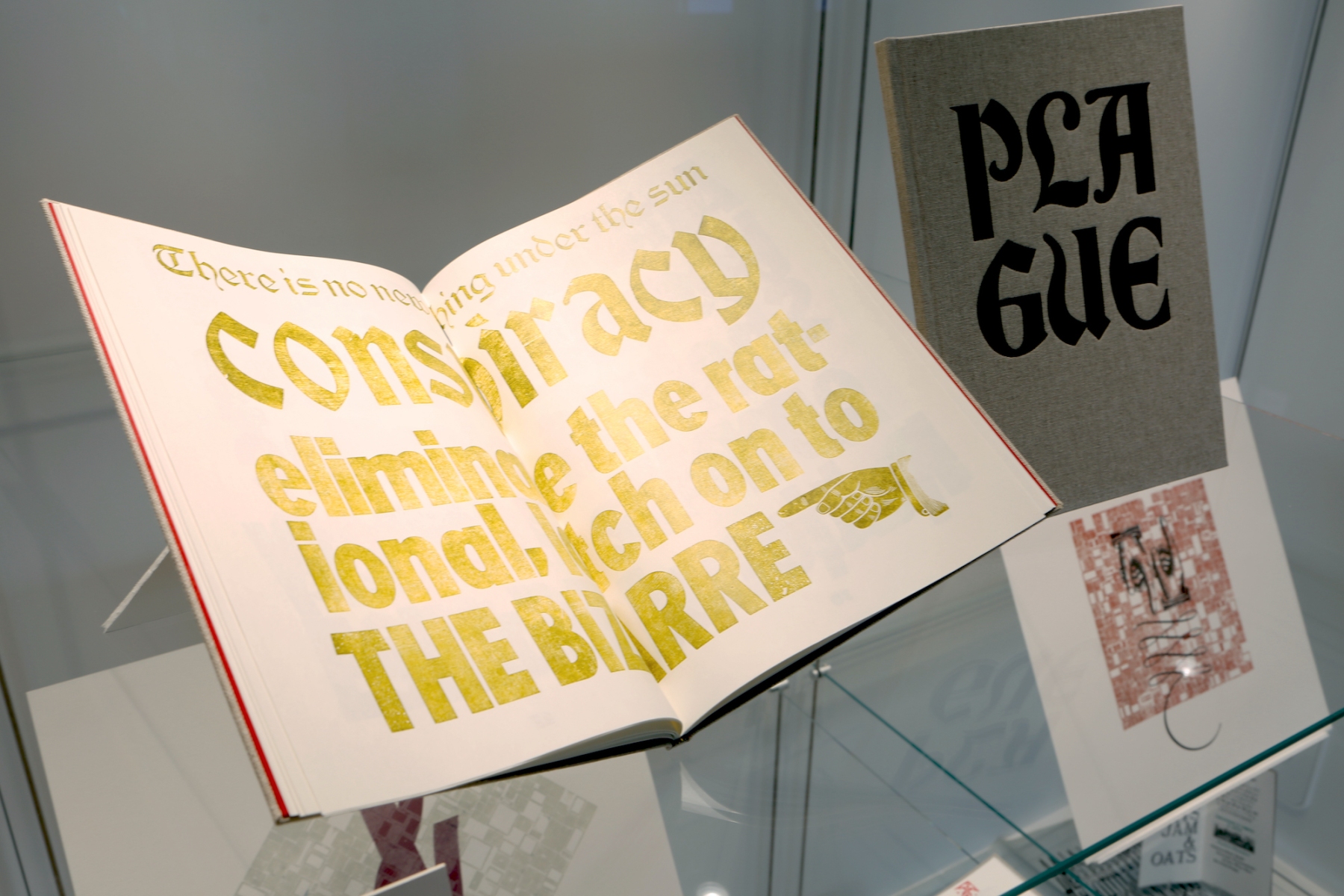

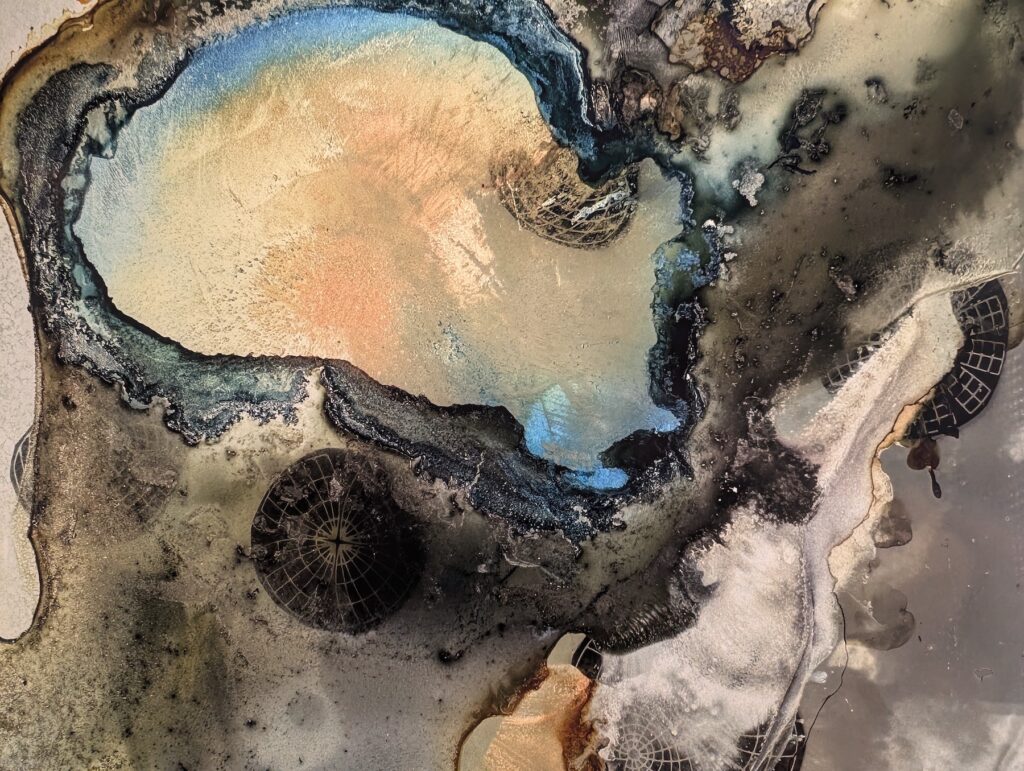

While Walker revels in moving through modern urbanity, Loi Magill’s ink works are a visual dirge for the cost of human activity to nature. An abstract map of the Anthropocene that responds to the environmental impacts of extractive industries, Data Mining (2024) has all the uneasy beauty of an oil slick rainbow. Mystic colours seem to seep across glass and are made more vivid by carefully placed backlighting, but synthetic emblems suggestive of mechanical worlds bring the eye back to the cartographic: suddenly the seeping rainbow appears as a rot on the land. Both this and her other work, Toxic Reality, with desert-toned ink on a roll of drafting film that is unfurled on a low plinth, bring important narratives of climate destruction to the fore.

A desire to escape the pressures of our own bodies and the efforts of facing up to the mundane and monumental challenges of life are similarly explored in works like Nathanlie Marie’s Talking to myself (2024). A ceramic pool with a red slide is guarded by a white lifesaver’s chair and preservation ring, but no one is on duty. This small work is a reflection of the urge to shirk that overwhelming pressure of work or self care or taxes, retreating instead to a floating world set apart from life’s tasks. Sonia Jane’s The Sum of the Parts (2024), a riot of colour and textures on a folding panel set in the centre of the UniSQ Art Gallery, encourages us to dive into art as a healing escape. With small books to explore, dripping paint to trace, and tiled accents to feel, this work invites visitors to lose themselves in the sensory.

Jane Orme’s two works are deeply personal, cataloguing battles within her own body and mind. Peri (2024), a series of 42 midfire clay cups in an soot-coloured glaze, is an homage to her age and the average age of the start of perimenopause. Her didactic notes perimenopause is a health problem “hidden or neglected in mainstream medicine” despite its impact on women, transfolk, and gender diverse people, and hopes the work allows “knowledge to rise from the shadows.” Her work Body (2024) dominates a far wall in the UniSQ Art Gallery. A video shows her hands squeezing the unfired clay ‘worms’ that lie in neat rank and file on a low dias in the gallery. This tactile process, she writes, helped her renew her artistic practice after a period of burnout and exhaustion in a “return to clay, and in turn, a return to my own body.”

Expanded Lemonade coverage of 2024 graduate exhibitions is kindly made possible by Lemonade’s Patreons and Charmaine Lyons. Lemonade is continuing to fundraise for four further reviews. Become a Patreon or contact editor@lemonadeletters.com.au to make a one-off contribution and support this unique coverage of Queensland’s emerging artists.

Zoe Devenport is a writer, historian, and journalist, formerly at the Mackay Daily Mercury.