Through a haze of midday sun and ever-closer-creeping bushfire smoke, I walk toward Queensland University of Technology’s (QUT’s) Creative Industries Precinct to visit this year’s Bachelor of Visual Arts graduate exhibition, inFORM. Like most university graduate showcases, the exhibition is installed in the institution’s emptied artist studios: inside a cluster of “heritage-listed” former army barracks buildings on never-ceded-but-taken Jagera and Turrbal lands at Kelvin Grove. As I enter, I think about ‘heritage,’ about which and whose heritages are preserved and celebrated. Following the cues and clues hiding in the exhibition’s title, I start to ponder the relationship between form and content, between what art says and what art does, and I question the usefulness of artmaking in the world of our troubling times.

A sound—low and rhythmical, like a long timpani roll—summons me into a white room densely filled with works by multiple artists: abstract black and white photography, suspended and stitched cyanotypes, bedazzled calico, ceramics, salt, and a technicolour photo montage. I search for the sound and find it emanating from a large water-filled steel bowl in the centre of the room: thrum, thrum, thrum. This is Dean Ansell’s Language of Resonance, a site-responsive body of work which, along with a nearby painting, derives from field experiments with sound and water. I am intrigued by the artist’s decision to fill the steel bowl with butterfly pea flower- (clitoria ternatea) infused water. Google says this plant has many culinary and medicinal uses in its traditional contexts (such as India and Asia) but it is considered an invasive weed in so-called Australia.

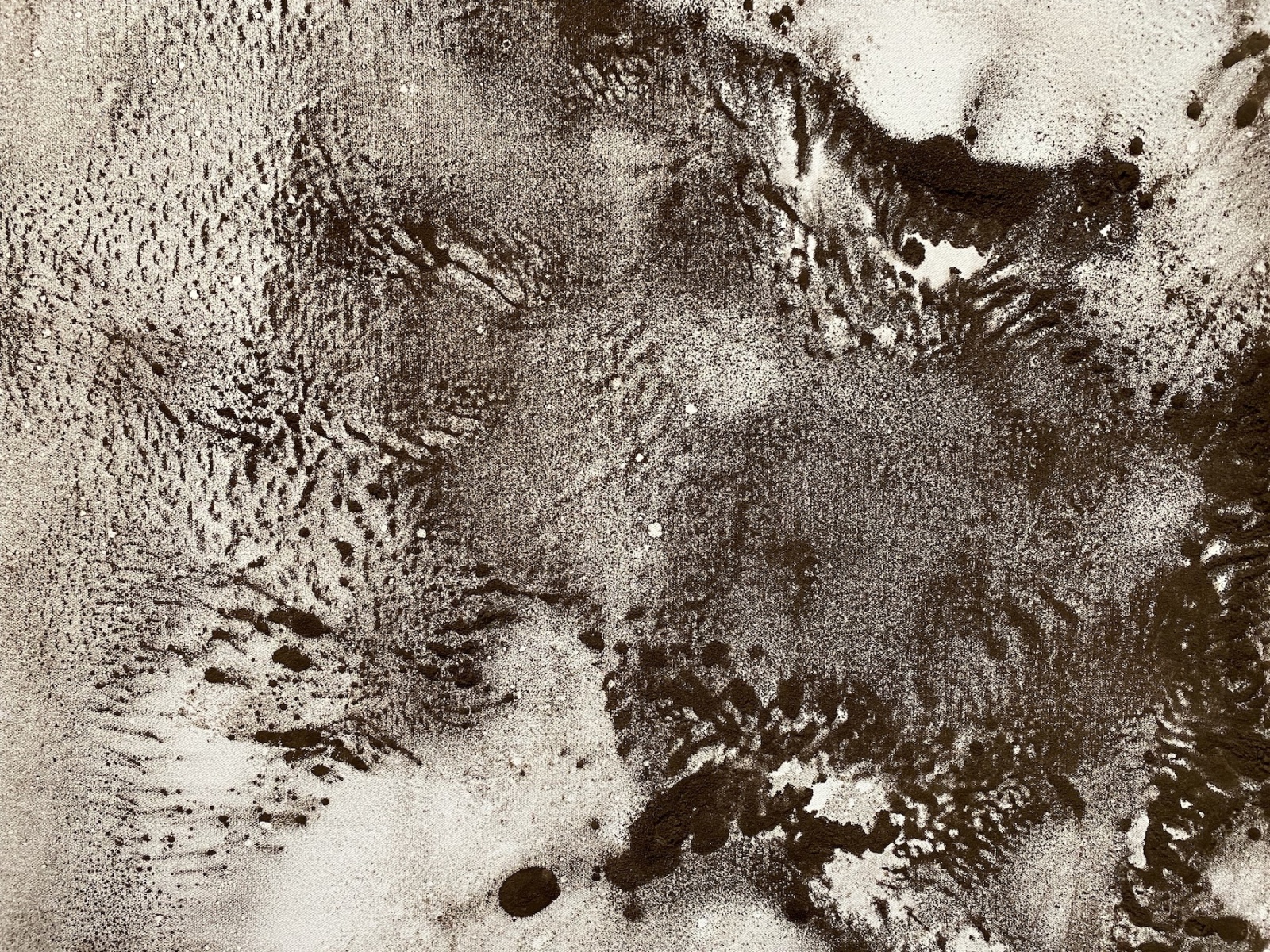

On the adjacent wall, a canvas is covered with soil that has been dispersed using sonic vibrations. The evocatively layered surface is translucent with pools of dust here, organic blobs there, and smatterings of staccato patterns throughout. It is tempting to dwell on the painterly qualities of this work or to evaluate Ansell’s deferral of their gestural capacity to a technological apparatus, but I rather find myself searching, reaching for the site in this site-responsive work. Miwon Kwon insists that “both the art work’s relationship to the actuality of a location (as site) and the social conditions of the institutional frame (as site) are subordinate to a discursively determined site that is delineated as a field of knowledge, intellectual exchange, or cultural debate.”[1] But in this instance, the absence of specificity around the actuality of the location (as site) hinders the work’s ability to arouse discursive associations. Which bodies of water were used in the field experiments: a backyard pool, a sacred waterhole, a puddle? Where does the soil come from (by which I mean: whose land sits across the surface of that canvas)? Though Language of Resonance might be read as a sophisticated and sensitive meditation on more-than-human energies or agencies, the generic treatment of land in this instance risks evoking rather than critiquing this colony’s fraught history of non-Indigenous representations of country.

Similarly, Olivia Pozzi’s Transcendent Landscape ignores the complexities of landscape in her large digital print juxtaposing various references to the outback—the beach, the suburban, and the urban. Starting from the left, big red rocks, eucalypts, and wildflowers butt up against wire fences and vernacularisms like weatherboards and tin rooves. In the middle, a hot pink Akubra bleeds into a suburban dreamscape of wheelie bins, concrete, bricks, and pink skies. Finally, to the right, paperbarks, ocean, banksia flowers, and a muscle car merge to form a technicolour surfie dreamscape. With its array of disparate ‘Australiana’ references stitched together, this imagery is reminiscent of soda_jerk’s audio-visual collage Terror Nullius (2018). But where soda_jerk’s approach splices together carefully selected images and sounds from Australian film and television archives toward a radical critique of contemporary politics and race relations, Transcendent Landscape focusses on personal references to (in the artist’s words) “enjoyable and nostalgic elements of land.” It is puzzling to encounter such untrammelled appreciation of landscape as an aesthetic object, given the extent of the colonial violence written there. I would encourage a deeper and more complicated engagement with landscape, a broken tool that can nevertheless be put to work.

Moving into the main gallery, I’m confronted by an overwhelming variety of interdisciplinary incursions and thematic interests (exactly what could be expected from an open-studio or post-disciplinary program of this kind). Standouts include Lucinda Pimm’s exploration of abstracted forms and patterns using airdrying clay, fabric, and paint; Xiu Li’s melted gummy lolly sculptures (can you smell them?); Izzy Heaton’s hair and spit paintings; Louella Michael’s meticulously constructed cardboard magistrates; and Mercedes Kent’s soft toy hybrids. I’m drawn to Ruby Stevens’ Can’t Work That Way (Missed Cues), which uses a toy robotic arm embarking on a doomed baking assignment to playfully examine gendered labour. The little black and yellow gadget attempts to tip flour and eggs into a bowl, clumsily; things are spilt and broken while the little bot’s engine whirrs on overdrive. This work takes me back to Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Can’t Help Myself (2019), in which an industrial scale robot arm continuously—and anxiously—sweeps blood-like fluid inside a glass atrium. There is a sense there, and here in Stevens’ work, that the apparatus is sentient, it feels, and that we the witnesses might be able to feel something too. Importantly, like Yuan and Yu’s vision, Stevens’ image of the cyborg doesn’t merely illustrate the problem it attempts to critique, but enacts a transformational reimagining labour and gender. As Donna Haraway explains, the cyborg:

suggest[s] a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves. This is a dream not of a common language. But of a powerful infidel heteroglossia . . . it means both building and destroying machines, identities, categories, relationships, spaces, stories.[2]

Zoe Hawker’s Horse Girl (coven) World captivates my attention with its sea of feeble-seeming plaster horse sculptures swirling around the cowhide skirt-tails of a large cartoon horse effigy. Behind the horse (where the hooves are the hardest) a television screen lays on the floor playing grainy footage of paddocks, blue skies, white laundry flapping in the wind, the artist in various horse-related costumes, and the occasional flash of the aforementioned plaster sculptures (actually more like a ham-fisted druid motif) laid over cracked earth. Despite (or because of) a slight clumsiness of execution, something in this combination of things suggests an orientation toward the world that is open and unfixed, curious and strange. I’m thinking about Daniel Coffeen’s explanation of immanent reading, which is “not a matter of fixing a thing in place but of propelling it into new territory, discovering its networks, how its tendrils reach across time, place, discipline.”[3] With its bad processes and narratives of a failed horse-girl mythology, its awkward familiarity and echoes of the uncanny, Hawker’s installation successfully “allows the strange to speak.”[4]

In the very last corner of the very last (actually the first) space, Ana Daniels’ Invitation explores the creation and embodiment of queerness. The installation features a large handmade checkerboard quilt in the centre of which are two slits with raw edges neatly bound and four floppy trunks. Eventually I understand that these holes are intended for heads and these trunks are sleeves for arms: that this quilt is a hugging quilt (nearby photo documentation of people embracing and stroking each other’s faces confirms this). Sure, we have seen plenty of quilting in the recent craft resurgence, but this is not just a quilt. It’s an artefact from the queer future-present that lays motionless and incomplete on the floor, waiting. This quilt is not an object but, as the title suggests, an invitation; it’s an opening, a space, a stage for queer bodies, and a collaborative performance of queer futures.

QUT’s inFORM presents a diverse collection of creative responses to various social, political, personal, and cultural phenomena. At times, these responses seem to be worryingly without anchor or lacking in historical, disciplinary, or theoretical awareness. But then in other moments, it is clear that while there is always room to grow, these emerging artists are asking some hard questions and avoiding easy answers. For better or worse, they are compelled to respond to the worlds of our times through creative action, and for this I applaud them.

[1] Miwon Kwon, ‘One Place after Another: Notes on Site-Specificity’, October (Spring, 1997, Vol. 80 (Spring, 1997), p. 92 pp. 85-110.

[2] Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” The Socialist Review (1985) 100-101.

[3] Daniel Coffeen, Reading the Way of Things: Towards a New Technology of Making Sense (Washington: Zero Books, 2016) 139.[4] Coffeen, Reading the Way of Things, 140.

[4] Coffeen, Reading the Way of Things, 140.

Expanded Lemonade coverage of 2023 graduate exhibitions was kindly made possible by Lemonade’s Patreons and generous contributions from Alex Baxter, Amanda Bennetts, Kylie Harries, Lynn Hughes, Kit Kriewaldt, Pippa Macgill, Merilyn & Steve Mayhew, JM Orme, Alethea Richter, Monica Rohan, Adrian Smith, Gavin Smith, Leisa Turner, Hannah Williamson, Nadya Wilson.

Lemonade is continuing to fundraise for three further reviews. Become a Patreon or email editor @ lemonadeletters.com.au to support this unique coverage of Queensland’s emerging artists.

Sally Molloy is an artist, writer, and educator living in Meanjin/Magan-djin/Brisbane.