Freedom is a place—you’ll know it when you feel it.

—Tulleah Pearce with Raphaela Rosella, You’ll Know It When You Feel It, exhibition catalogue (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2023).

The official archive is a place of disempowerment, displacement, and injustice.

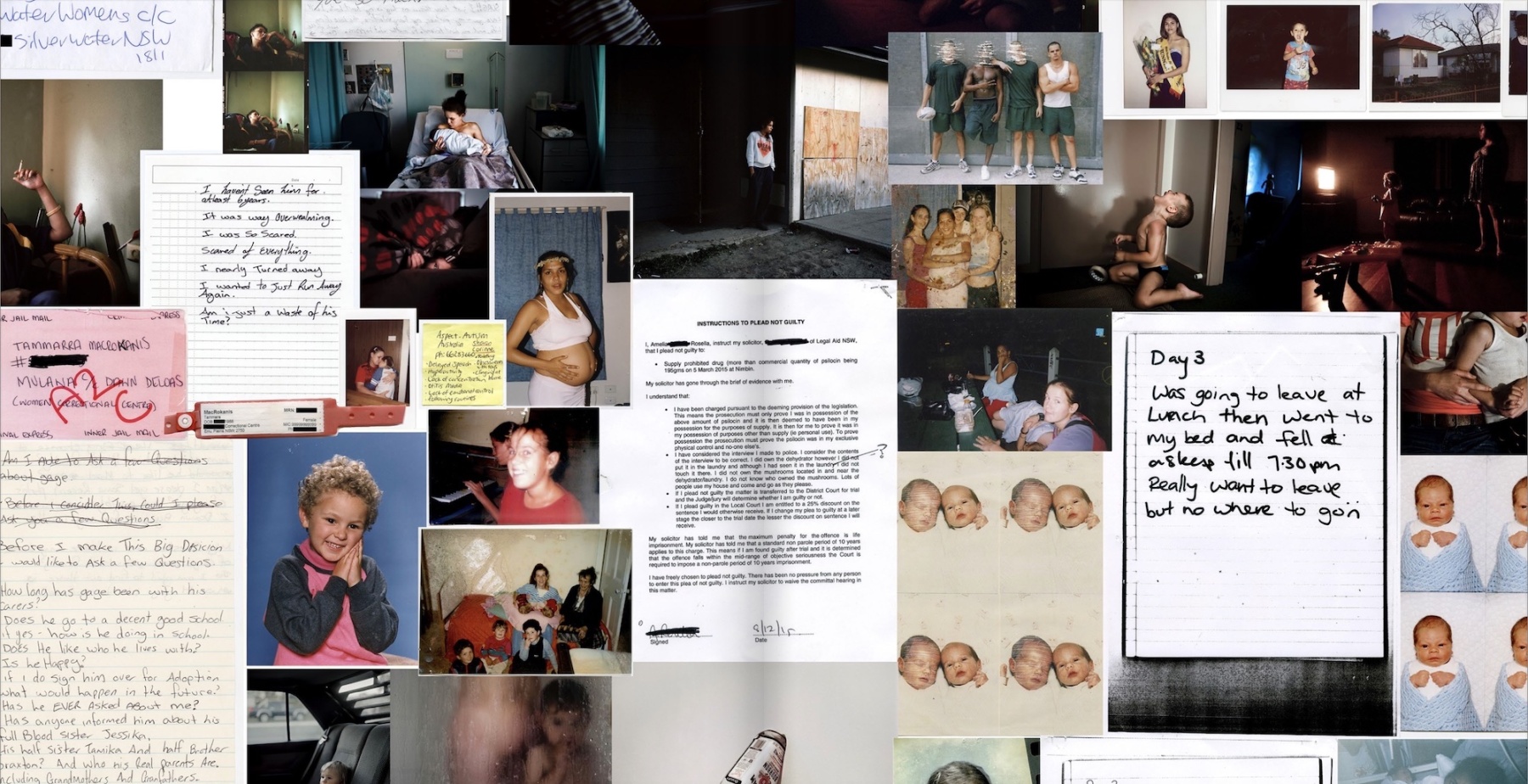

For photographer Raphaela Rosella and her collaborators, Dayannah Baker Barlow, Kathleen Duncan, Gillianne Laurie, Tammara Macrokanis, Amelia Rosella, Nunjul Townsend, Laurinda Whitton, Tricia Whitton, and their families, the official archive that details their lives is populated with court papers, police statements, and case files. It depicts them as criminals of the State, failing to see them as loving mothers, daughters, sisters, partners, aunties, and friends. In the violent, bureaucratic and heavily-surveilled system of the official archive, they are collateral. The documents of the official archive are used repeatedly against them, enabling a revolving-door of incarceration instead of identifying their social conditions and vulnerability.

From these conditions, You’ll Know It When You Feel It began as a counter-archive: a place where care, pain, love, and community is shared. This archive spans 15 years and ranges from intimate photographs of mothers holding their babies and children playing against suburban backdrops, to personal letters, cards, and 6-minute phone call recordings from within prison walls to outside and back again, to redacted court documents. In this archive, Raphaela depicts people she has known for most of her life, who have intersected with the carceral state, with care. As co-creators of this archive, Raphaela gifts them, friends and family, the agency to tell their own stories.

The nostalgically familiar draws me into the exhibition at the Institute of Modern Art, where the archive is displayed across three rooms. Creedence Clearwater Revival plays in the background of an analogue TV where a couple dance in a backyard. Behind it, a curtain stages a recognisable place: the homely lounge room. Here Raphaela establishes a line between the painfully intimate and the universal that carries unpretentiously throughout the exhibition.

Each wall is dedicated to the experience of one collaborator. And within a wall, the same person is portrayed via the personal and the official archive, contrasting their languages of care and surveillance. For example, text from a court transaction turned into wallpaper notes: “I have read and understood the statement of truth.” In the centre is a portrait of the collaborator, Nunjul, and her son, their eyes closed in a gentle embrace. They sit in a body of water, softly lit by sunshine. In this display, Raphaela calls into question the legal definition of truth (the actual state of things), which has portrayed Nunjul as an ‘unfit parent.’ Raphaela contrasts this with another truth in the image of a mother loving her son.

From afar, the focal point in the second room is an altar-like archival wall. I’m drawn to the way this work gently grows as I move closer to it. My eye settles on a handwritten letter from Amelia, Raphaela’s twin sister. Amelia’s words reveal a transformation: in the mind, the body and perspective. Via Amelia, I come to understand this transformation was not a result of incarceration, but of connecting to self and loved ones through the counter-archive. HOMEtruths extends this component of the counter-archive. The three-channel film fills my field of vision, placing the viewer in the archive and amplifying its elicitation of connection, friendship, and nostalgia.

On the day I visit the exhibition, Raphaela, Amelia, Kathleen, and Nunjul are in the gallery to talk about their project. As I take my seat at the back of the room, the conversation from family, who are seated beside me, reminds me that this work isn’t made for me as a gallery visitor. This is the most captivating component of this exhibition: that the archive is for the people to whom it matters most, creating a place of safety and healing for them. Its display in a gallery context is only a by-product of those personal relationships and that purpose. As the creators talk through the difficult conversations and painful experiences of remembering and representing their lives in the archive/s, they hold each other, crying and laughing, with radical care: a resistance to being controlled in and out of prison.

Freedom ‘as a place’ for the creators remains under threat when all levels of Australia’s so-called justice system continue to incarcerate their loved ones and perpetuate bureaucratic systems of violence. Against this, I feel the deep warmth that emanates from the counter-archive, looking through Rosella’s lens as she and her collaborators tenderly defy systems of oppression. You’ll Know It When You Feel Itdemonstrates the very thing that our society needs: a community built through unconditional care, kindness, empathy and above all, love.

Jocelyn Flynn is Notsi from Niu Ailan province, Papua Niugini with Anglo-Celtic lineages. She researches, writes, mediates and curates critically engaging projects.