Reflecting recently on Michael Zavros’ portraits of Ben Roberts-Smith, which were commissioned by the Australian War Memorial,[1] Rex Butler and Paris Lettau find, not just what is wrong with contemporary attitudes to war, nor even just what is wrong with the artwork of Zavros, but instead find distilled in this pair of paintings everything that is wrong with…well…everything: “Altogether Pistol Grip and Ben Roberts-Smith VC are masterpieces of a sort. They are outstanding examples of our ideological end times and the emptying out of all moral, political, and artistic values.”[2]

A few short weeks after the publication of this remarkably damning statement, QAGOMA opened the largest survey of works by Zavros yet staged at a state gallery, The Favourite. The exhibition is part of the gallery’s ongoing ‘blockbuster’ exhibition series, which is supported specifically by the Queensland Government to ensure ‘world-class’ exhibitions. In this dual context, of both strident criticism of Zavros by one of Australia’s leading art historians and enormous support for Zavros by QAGOMA, the exhibition merits close attention and careful consideration.

The Favourite has been paired with a large solo survey exhibition by another Australian artist, eX de Medici. Beautiful Wickedness is overtly concerned with militarism and perpetual global conflict and includes a de Medici work loaned from the collection of the Australian War Memorial.[3] Perhaps unsurprisingly, Zavros’ portraits of Roberts-Smith are not included in The Favourite. Nevertheless, the spectre of these portraits necessarily haunts the exhibition, which is composed mainly (but not entirely) of the photo-realistic paintings of luxurious objects and spaces for which Zavros is most known. The two exhibitions, both presented in the GOMA building and offered together on a single ticket, have been marketed in tandem and, as such, invite a shared reading.

The marketing campaign for the exhibitions includes the tagline, “Two irresistible exhibitions,” with ‘resist’ highlighted within ‘irresistible.’ It’s a typographical conveyance of the idea that one can hold two conflicting positions simultaneously. It could be referring to the relationship between the two exhibitions, distilling the narrative of the media releases which contrast the artists: de Medici is defined as the politicised activist (‘resist’), and Zavros as the unapologetic aesthete of consumerism (‘irresistible’). Yet it could equally be applied to the conflicts internal to The Favourite. We see this in a relatively obvious way via Zavros’ own commentary in the exhibition catalogue, which hints at consumerism as a site of both seduction and resistance. For example, regarding fashion, from which his work often draws, Zavros states he is attracted to its ‘excess and decadence’, yet also feels ‘guilty’ about this.[4]

The ‘irresistible’ marketing conceit also brings to mind the overlapping, yet duelling, interpretations of Zavros’ work in the writing of Rex Butler and Robert Leonard, who have both written several texts about his work over a number of years. For Leonard, there is something appealing about Zavros’ work in the way it acts as an affront to the assumption of criticality, or resistance, in contemporary art:

“By picking subjects that seem prime candidates for deconstruction and critique but not deconstructing or critiquing them, Zavros foregrounds and flaunts his lack of criticality . . . For me what is so sharp about Zavros’ art is how utterly, rigorously and deliberately uncritical it is . . . The apolitical may simply enjoy these interiors as arrangements of self-evidently nice things, but those who make political connections will do so quickly. However, beyond prompting these political points, the paintings have nothing to actually say about them.”[5]

This is an idea that Zavros himself seems to agree with. In the catalogue interview with Peter McKay, Zavros states that he is not interested in attempts to find political meaning in his work, which he sees as typical of contemporary art discourse.[6] Indeed, Zavros considers art’s critical discourse (or, as he calls it ‘self-importance’) to be “tedious”, especially compared to the fun utopia of fashion: “Fashion isn’t going to save the world, but neither is art.”[7] His own work then, like his interpretation of fashion, is assumed to be simply an apolitical, yet irresistible, fantasy. For Butler, Zavros’ work reveals the impossibility of logically maintaining such a ‘post-critical’ stance, partly because the work is reliant on attaining this status via art criticism (as in Leonard’s writing). The stakes here come into sharp relief via Butler’s consideration of CJ Hendry, another (previously) Brisbane-based artist who draws photo-realistic images of luxury goods. Hendry, unlike Zavros, operates outside of ‘serious’ artistic contexts and critical discourse: selling work via her own website, advertising exclusively via social media and having a manager, rather than being represented by an art dealer. As Butler notes, the criticism levelled at Hendry by Philip Bacon, Zavros’ art dealer, and his attempt to distinguish Zavros from Hendry, only serves to highlight the way that the viability of Zavros’ supposedly critically detached practice is not outside of the critical discourse of art, but reliant on such contexts, in which we could include the mounting of The Favourite at QAGOMA.[8]

Regardless, Zavros’ work continues to position itself as uncritical and autobiography is often invoked both as an alternative discourse[9] and as a method for deflecting criticism. Autobiography manifests in various ways, both in his work generally and in The Favourite specifically, which demand consideration. For the media preview Zavros provided a brief tour filled with personal anecdotes offered as explanations for various works. Zavros began by discussing the work that first gained him wider attention: his small paintings of sections of men’s suits, based on images taken directly from fashion magazines (twenty of these are exhibited at GOMA). Typically, in twentieth-century painting, men’s suits were used to invoke the bureaucratic anonymity and alienation of an administered working life.[10] In a radical divergence, Zavros reclaims the suit from social contexts and restores it as a decontextualised expression of luxury and aspirational masculinity. His painstaking painted recreations demonstrate reverence for the images of fashion advertising from which they are sourced. Curiously, however, Zavros describes the works via autobiography. He notes that the original image for the first of these paintings was collected during his search for a suit to wear to his own wedding, with the collected image demonstrating some of the attributes he was looking for in a wedding suit.[11] While it initially seems odd for Zavros to define such generic images[12] within a personal narrative, it is a stance that makes perfect sense if we more carefully consider the concept of ‘luxury’ that animates so much (if not all) of the work in the exhibition. Noam Yuran is a useful guide here. Yuran writes that luxury is defined by being excessive, more than is needed, but is also based on a particular emphasis on the subject:

the luxury good is an excessive object because it contains something of the subject (as suggested by the popular luxury advertising formula: ‘you deserve more’). Luxury implies an intense subjective attitude. […]. Because it invokes intense subjective attitudes, luxury is one way in which objects shape subjectivity.[13]

Here then, we can understand that Zavros’ link of luxury to personal narrative is, perhaps, inevitable.

While the exhibition is concerned with branded luxury commodities (Mercedes Benz, Gucci, etc) it is also interested in art as luxury, with various artworks being reproduced by Zavros within the context of his paintings of luxurious interiors.[14] One of these, Unicorn in the Anticamera (2008) (from the QAGOMA collection) had previously featured in a Michael Zavros project at QAGOMA in 2013, A Private Collection. This project bears consideration in regard to understanding the nexus of Zavros, luxury and ‘intense subjective attitudes.’ A Private Collection was part of a series of exhibitions in which artists were asked to curate an exhibition with works from the QAGOMA collection. Zavros’ approach was to imagine these collection objects as part of the home of a private collector, using the collection to recreate the type of scene we might find in one of Zavros’ paintings of ‘luxurious’ interiors. The project’s commitment to the conceit is laudable, and the catalogue text purposefully takes its design cues from fashion magazines, suggesting we are being taken on a tour of the private collection of a wealthy individual, some sort of ‘financier’, and being offered glimpses of this person’s ‘figuration room, ‘still life room’, ‘white space’ and ‘Narwhal room (amongst others).[15] This last room both contains, and is inspired by, Zavros’ Unicorn in the Anticamera, a painting of an aristocratic interior (which like this room, includes a Narwhal tusk). The ‘idea’ of the project is to subjectivise and individualise a publicly owned collection. Zavros’ chance to work with a significant public collection is leveraged in the service of a fantastical recreation of private ownership and a (fictional) individual seeking personal fulfillment via “new and different encounters,”[16] which, according to the logic of the project, manifests as the ownership of precious objects. A Private Collection reclaims a publicly-owned resource (the QAGOMA collection) to emphasise that the proper place of luxury (which includes art) is as a private asset in the service of the development of the self, and as an expression of the self. And The Favourite continues and extends upon this logic.

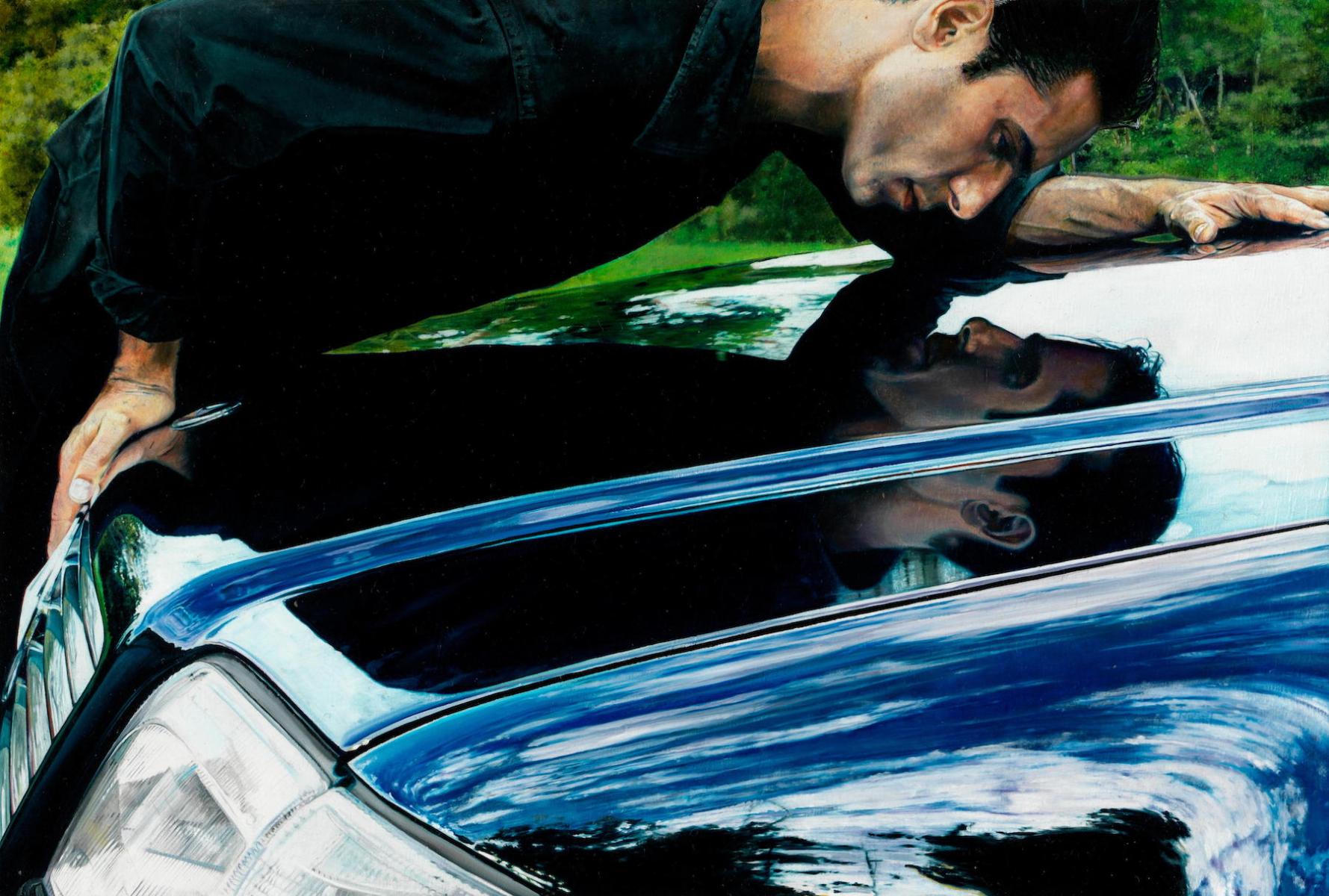

To return to the media preview, Zavros’ autobiographical approach to describing his work continued as he discussed one of the major commissions for the exhibition, Drowned Mercedes (2023), a Mercedes-Benz convertible filled with water. Without context, an initial reading of the work might be to see it as a succinct statement regarding the way that our obsession with consumerism is leading to climate change and a drowned world.[17] Zavros, however, spoke of owning a similar car that he would park under his flood-prone house. Furthermore, the car connects to his memories of visiting Mercedes-Benz showrooms with his father and aspiring to one day own such a car. One might assume that this anecdote of Zavros and his father wanting to own a Mercedes-Benz is so banal as to be completely uninteresting to anyone other than Zavros and his father. Yet, because Mercedes-Benz have featured in several of Zavros’ works over the years, most notably the self-portrait V12/Narcissus (2009),[18] this anecdote has been repeated in print several times, including in two essays by QAGOMA director, Chris Saines.[19] The specific choice here of Mercedes-Benz as the symbol of aspirational ownership inevitably recalls the iconic Janis Joplin song, ‘Mercedes-Benz’, and its amusing, but still trenchant, critique of faith in consumerism as a path to self-actualisation. Indeed, the specific choice of the Mercedes-Benz in Zavros’ work may well be a pointed reclamation of this brand from Joplin, restoring it as a symbol for the celebration, rather than criticism, of fulfillment via conspicuous consumption.[20] The discursive repetition of this mundane anecdote is so comically absurd that it would seem to be parody, perhaps designed to elicit laughter. Yet, it is relayed by Zavros and Saines seemingly without irony as though it is relevant and insightful context for understanding Zavros’ work. And, as such, I will also be taking this interest in Mercedes-Benz seriously, and will return to it.

For now, we can note that this repeated structure, which interposes biography as the frame through which Zavros’ work must be interpreted, acts as a strategy to deflect criticism by turning criticism of the work into a personal disagreement or attack. Indeed, Zavros seems preoccupied with the idea that people don’t like him.[21] The only time I have spent in the presence of Michael Zavros, the person, was at the media preview, where his presentation was engaging. He came across as likeable, warm, sentimental even, with his talking points rehearsed in a way that demonstrated, not mannerism, but a respect for his audience. Appropriately, I don’t really have anything to say about Michael Zavros the person. Yet the intense linkage of his work to autobiography, via accompanying texts and interviews, has the effect of disarming any critique of the work, because to talk about the work is to talk about ‘Michael Zavros’: it isn’t real criticism, it is just someone who doesn’t like Zavros and the fact that he likes nice suits. The exhibition, and its marketing and other collateral, is completely obsessed with presenting ‘Michael Zavros’ as the locus through which the work must be interpreted, such that even many of the didactics set next to the exhibited works are quotations attributed to ‘Michael Zavros’, rather than more typical anonymous curatorial notes.

This creates a curious tension in the work, where it presents a distinct and highly politicised vision of the world (fashion advertising as utopia, for example) but is wrapped in autobiography, suggesting this is simply a personal expression beyond analysis or critique: it’s just Zavros being Zavros. Occasionally, we can see this tension manifest at a micro-textual level within the work. Take for example his iconic painting, The Sunbather (2015).[22] This work presents a self-portrait, with Zavros lying naked along the edge of a pool, his hand on the surface of the pool as he stares at his reflection in the water. Zavros’ body is reflected in both the pool water and in the glass pool fence behind him. As Leonard has noted, the work seems to directly reference David Hockney’s The Sunbather (1966), Caravaggio’s Narcissus (1597-99) and Zavros’ previous paintings that invoke the myth of Narcissus.[23] It is a seemingly idealised image, presenting a trim, tanned body that invokes specific standards of beauty. As Leonard writes: “Zavros offers up his own pert bum for his and our pleasure.”[24] On one level the work seems to invoke (perhaps even revel in) a contemporary social context where the multiplication of images of the self leads to lethargic self-absorption (a crucial difference from the Hockney painting, which does not include any reflections). However, in a key detail, we find in this painting a small squiggle reaching up along the figure’s hip. The squiggle seems uncharacteristic of Zavros’ work given his usual fastidiousness with maintaining smooth canvases that reveal neither the fibre of the surface, nor the mark of a brush.[25] Though I was initially puzzled by this detail, thinking perhaps it was a rendering of a stray pubic hair, Leonard specifies that in fact the squiggle spells ‘Ali’ and is a tattoo referring to Zavros’ wife, Alison Kubler.[26] It is a strikingly intimate detail that looks like a signature, and also acts as one of sorts, in that it identifies the figure as the ‘real’ Michael Zavros, rather than an idealised version or a stand-in for a broader social context. The implication is that this is simply an accurate image of Michael Zavros, warts and all, and nothing else.

Autobiography is central to The Favourite and to Zavros’ practice in general. One of the more interesting, and often remarked upon aspects of this, is that the sales of Zavros’ paintings of luxury have allowed him to afford a lifestyle filled with the objects that he paints.[27] As Butler writes, Zavros’ work “is auto-biographical, we might say, not merely in the sense that it is expressive of some actual being and desire of the artist, but in the sense that it is calculated to bring about the things it represents.”[28] For me, such observations connect Zavros’ work to another text that, in a succinct parallel, expresses this same relationship between painting and things: The Magical Life of Mr. Renny, an illustrated children’s book by Leo Timmers.[29] This is perhaps an unusual reference point, but one that will lead to further illumination of the way that Zavros’ work, and The Favourite, specifically, function.

In this book Mr. Renny is a painter who is granted a magical ability in which whatever he paints becomes reality. He begins by painting food but quickly moves to creating a life of luxury, which includes many of the things we might find in a Zavros painting: a silk suit, crystal glasses, an ornate bed and chaise lounge, perfume, a statue, multiple cars, and even a swimming pool whose flotation devices, as presented in Mr. Renny, recall the colour palette of Zavros’ Bad Dad (2013). I think back to Zavros’ media preview statement about Drowned Mercedes in which he recounted that his art dealer owned a similar car, which he coveted, and eventually purchased from her with paintings as payment. The similarity of Zavros to Mr. Renny is striking.

But it is the conclusion of Mr. Renny that specifically interests me here. In the end, Mr. Renny laments that he can no longer produce paintings, merely things, and gives up his magical ability (and as such all of his things turn back into paintings of things). With his ability to create paintings (that don’t turn into things) restored, Mr. Renny gifts a painting to his friend Rose (a painting of a rose, of course). So, in the end the book valorises painting and the idea that Mr. Renny is above all things a painter. This is an idea we find reflected in The Favourite. The exhibition is preoccupied with valorising the act of painting and with emphasising Zavros, the painter. It seems at pains to show that Zavros is not just a consumer, but a worker. As such, the catalogue presents a bizarre compendium of images of Zavros painting. It features not only images of him in the studio or making works (of which there are at least a dozen) but additionally includes many large close-up shots of Zavros in studied concentration, his brush against the canvas.[30] There are two such images (both double-page spreads) before we even reach the foreword of the catalogue, and at least ten more scattered throughout. The images belabour how much labour goes into the work, suggesting there is something inherently positive in this monastic pursuit of painting as tedious and diligent process. Such images are in addition to those in which Zavros is photographed holding his works. By way of comparison, the (longer) catalogue accompanying de Medici’s concurrent exhibition includes only a single shot of the artist working (installing a public work in 1987)[31] and a single shot of her holding a reproduction of one of her works (on the final page): there are no images of de Medici in the process of painting, though almost all of the exhibited works are detailed, labour-intensive watercolours. Of course, unlike Mr. Renny, Zavros’ paintings are typically worth more than the objects they represent because they are connected to his hand. In The Favourite, the valorisation of painting folds back into itself, as the exhibition serves to develop Zavros’ work as an asset in which QAGOMA has a vested interest (owning twelve of his works). While the images of Zavros, the serious worker, counter any suggestion of Zavros as a vapid consumer (‘you deserve this’), and help to deify his creations as objects of intense craft akin to, or beyond, the value of the things they represent.

A close reading of Mr. Renny offers a further, and perhaps more interesting, insight into The Favourite via the connection of Mr. Renny/Zavros to the work of René Magritte. The figure who gifts (and removes) Mr. Renny’s magical ability, dressed in a bowler hat and suit, is clearly designed to evoke Magritte. More overtly, the book begins with a painting of an apple under which it reads “This is not an apple,” before revealing the same image on Mr. Renny’s easel on the next page (“It’s a painting of an apple”). The reference is to Magritte’s famed work, The Treachery of Images (This is not a Pipe) (1929).[32] In an extended analysis of various versions of Magritte’s work, Michel Foucault argues that it embodies a move from ‘resemblance’ to ‘similitude’.[33] This is an idea useful for understanding Zavros and The Favourite. For Foucault, resemblance suggests a hierarchical and relatively direct relationship in which one thing (an image, for example) is made as a copy of another. In contrast, the unsettled play between word and image in Magritte’s work describes a different relationship, one of similitude. Similitude suggests a circulation of signs, each reinforcing the other via similarity, with no clear end nor origin: “similitude circulates the simulacrum as an indefinite and reversible relations of the similar to the similar.”[34] It is this circularity of similitude that The Favourite revels in, akin to the logic of the brands it portrays, where the repetition of the brand serves to elevate the brand in an endless cycle. Individual objects are not being sold, it is the brand that is sold. The functioning of a brand can be described by Foucault’s definition of similitude: “born from their own vapor […] to rise endlessly into an ether where they refer to nothing more than themselves.”[35] This is a logic doubled in The Favourite. Firstly, it exists within the exhibition’s incorporation of brands. So, we find Mercedes-Benz appearing across a photograph, paintings, and sculpture, all in circuitous referral to each other as a materialisation of the brand (and a dematerialisation of the objects, which are overtaken by the brand). It isn’t that the painting of the car resembles its object, but that the painting and the car are equivalent as materialisations of the brand. These artworks don’t refer to the physical car that they represent, they all refer, in a circular logic, only to ‘Mercedes-Benz’. [36] Secondly, and more significantly, the logic of similitude is one that extends to the exhibition itself, and its construction of Michael Zavros as a brand, which supersedes and incorporates all of the other brands, whose logic it doubles. This is achieved via the repetition of the brand, always across artworks, interviews and other collateral: Michael Zavros, Michael Zavros, Michael Zavros, Michael Zavros.[37]

The question, then, is what might the Zavros brand represent, if anything, other than itself? For QAGOMA director, Chris Saines, ‘beauty’ is a defining component: “At the core of the exhibition and among the things that differentiate Michael Zavros from other artists of his generation is an unapologetic love of beauty and craftsmanship, folly, and grandeur.”[38] In the opening sentence of an earlier essay, Saines again emphasises ‘beauty’: “Michael Zavros toils in the service of beauty.”[39] Of course Saines recognises that this is a very specific version of beauty: “His idea of beauty is urban, cultured and cultivated – there’s nothing quotidian or natural about it.”[40] Certainly, this is reflected in the exhibition, filled with luxury goods, including paintings of Rolls-Royce interiors, palaces, race horses, designer clothes and so on. Even the paintings of flowers are couched within their relationship to luxury: they are based on photographs of arrangements of real flowers and include rare blooms which fade quickly in the Queensland heat. To quote Zavros on these works, “there is a rarity to the work, an almost imperceptible layer of luxury I am highly aware of.”[41] Certainly, the work is explicit in declaring its idea of beauty as inseparable from the excess of luxury.

What is so troubling about this exhibition is not that Zavros’ work is used to define a concept of beauty inseparable from luxury (though that certainly is disturbing) but rather that this is the idea of beauty that QAGOMA has chosen to support and enable. That the exhibition revels in luxury during a cost-of-living crisis is, quite simply, incredibly weird. Indeed, at a time when there is an increasing attention to the way that social and class stratification is overdetermined by vectors of intersectional identity, the exhibition’s obsession with, and enormous space granted to, markers of extreme wealth read as a rather intense political statement. This enthusiasm for luxury draws attention, more so than usual, to the stratification within QAGOMA’s own structure, where the exhibited works (whose enormous value is enhanced by their exhibition within this context) are installed by casualised, precarious workers. For me, and likely for many, the images that the exhibition presents of domesticated animals and the homes of aristocrats, do not evoke beauty at all, they are grotesque, macabre even.[42]

I admit that this is a relatively obvious critique of the exhibition, and such a reading will not trouble the development of the Zavros brand, which is proudly bound to the stratification inherent in luxury. In terms of brand development, however, The Favourite presents another issue. The exhibition completely inhabits the interiority of Zavros’ work: there is a single entrance and exit, all windows to the outside have been covered, and the galleries are packed with works. Works are everywhere. In addition to the seemingly endless wall works, there are numerous sculptures scattered throughout. Looking out across the main room, containing Drowned Mercedes, set amongst walls of paintings and photographs, I was startled by something in my peripheral vision. Turning around I discovered it was a small sculpture of Zavros’ head (Trophy Dad, 2023), placed high on one of the walls. Looking beyond this, more sculptures were visible, set against a vaguely ludicrous row of faux columns. It is a complete overload. Amidst the various references to Greek mythology in the exhibition (Narcissus, Zeus and Leda), the one that most came to mind, in regard to the effect of the exhibition as a whole, was that of King Midas whose touch turned everything into gold. This myth suggests that too much of a good thing can only lead to boredom and death. This, however, may be the brilliance of the exhibition. In enacting the excess of the works at a curatorial level, it pushes this excess to its extreme, exemplifying “our ideological end times and the emptying out of all moral, political, and artistic values.”[43] But this also makes for a remarkably nihilistic and depressing experience. At the entrance to the exhibition, as if to prepare us for this, we are greeted by an enormous photograph of a mannequin wearing reflective sunglasses who resembles Zavros (Dad likes summer (2020)). The work suggests a detached nonchalance, a bored, disinterested and empty gaze. Another image of ‘Dad’ towers over us as we leave (Dad likes colour (2020)), this one with cucumbers over its eyes, possibly asleep. This Zavros doppelganger is done with engaging and just wants to chill, or maybe even the mannequin has seen enough (too much) and simply wants to close its eyes.

But the exhibition is not quite done with us.

In the huge central hall of GOMA, on either side of which sit the Zavros and de Medici exhibitions, there are two new super-sized versions of each artist’s work, placed across from each other in a kind of face-off of massiveness (and conflicting ideologies). Both works are relatively unusual contributions and are material outliers in the context of the artists’ broader contemporary practices. Zavros has created a massive mural-sized trompe l’oeil rendering of the Parthenon, Acropolis Now (2023).[44] The de Medici work facing this is a hugely enlarged and printed version of one of her works, depicting, in her usual style, an entwining of weapons and flora.[45] This places the two exhibitions in direct conversation, highlighting how both can be seen as different sides of the same coin. Both are concerned with capitalism, power and beauty; one of them is ‘about’ these topics, while the other enacts, or embodies, them in an intense political statement. Both artists manifest these concerns via precious objects carefully stored in enclosed, climate-controlled environments. Such works are not, apparently, appropriate to face the natural light and scale of this enormous hall, and so we have these rather curious, if massive, stand-ins for the works in the adjoining galleries.

The title of Zavros’, Acropolis Now, sets a relatively light tone, as it presumably refers to the sitcom of the same name, which was a rare example of Australian popular culture addressing the Greek migrant experience, and which aired during Zavros’ formative years.[46] Zavros himself describes the work in two ways. Firstly, he connects it to his increasing interest in his Greek heritage and describes it as a political statement in the context of the ongoing movement to repatriate the Parthenon Marbles. It is incredibly unusual for Zavros to ascribe a political meaning to his work, which he usually prefers to leave ‘open-ended’. Secondly, and in seemingly direct distinction to this ‘political statement’, Zavros considers the work to also act as a light “selfie-moment.”[47] The GOMA building is a descendant of the International Style of architecture, with large, uninterrupted and rectangular volumes of glass and concrete, and a lack of adornment. As such, the painting of an image of the Parthenon directly onto the walls of GOMA, inevitably suggests Le Courbusier, who was both a central figure in the International Style and obsessed with the Parthenon. Like Zavros, Le Corbusier’s concern was ‘beauty’, which he finds manifested in the Parthenon. Indeed his praise for the Parthenon is almost absurd in its rapture: “there is nothing like it in the architecture of all the world and all time”;[48] it is the ultimate example of “pure creation of mind.”[49] Yet there is also something to be admired in Le Corbusier finding, within the Parthenon’s distinct spatial arrangement, something towards which humanity should strive: “Passion, generosity, grandeur of soul: so many virtues that are inscribed in the geometries of the contour modulation, quantities manipulated into precise relationships.”[50] In contrast, for Zavros the Parthenon is simply something to be flattened into an image, appropriated within the ‘precise relationships’ of his photorealist painting method, and via this process transformed into little more than an image subsumed within the Zavros brand, towards which QAGOMA has demonstrated a committed brand loyalty.

[1] These two paintings are Ben Roberts-Smith VC (2014) andPistol grip (Ben Roberts-Smith VC) (2014).

[2] Rex Butler and Paris Lettau, “The Anti-Art of War” Memo Review, 4 June 2023. https://memoreview.net/reviews/the-anti-art-of-war-by-rex-butler-and-paris-lettau. This is a sentiment that connects to Butler’s previous critiques of Zavros, which, as Laurence Simmons notes, use his work within arguments suggesting a more general condemnation of our era. (Laurence Simmons. “Lives of the Artist” Michael Zavros, Sydney: Manuscript, 2017. p.15.)

[3] Cure for Pain, 2010–11, Watercolour on paper, 114 x 415cm. For more information on this work and de Medici’s other work in the Australian War Memorial collection, see: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2119165 and https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/ex-de-medici-exploring-camouflage-through-special-forces-helmet

[4] Quoted in Paola di Trocchio, “Guilty after a fashion: Michael Zavros’ menswear works” Michael Zavros: The Favourite, Brisbane: QAGOMA, 2023. p.156. The source of the quotation is from 2008; Zavros’ commentary since has tended to be less ambiguous.

[5] Robert Leonard, “Charm Offensive” Michael Zavros. p.74, 78. (Originally published in 2011).

[6] Peter McKay, “All about closer inspection: An interview with Michael Zavros” Michael Zavros: The Favourite, p.38.

[7] Rhana Devenport, “Self Portraiture and the Perfect Strangeness of Realism: Interview with Michael Zavros” Michael Zavros, 43. Zavros goes onto state that “More than anything else in popular culture, fashion articulates a utopia, a perfect world.” This is a peculiarly contemporary stance, given the centrality of art to historical conceptions of utopia (communism, socialism, etc.). This statement is also quoted in The Favourite catalogue (see, di Trocchio, p.158).

[8] Rex Butler, “Really Post-critical” Double Displacement: Rex Butler on Queensland Art 1992-2016, Eds. Helen Hughes and Francis Plagne, Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2018. p.193-201. (Originally published in 2016)

[9] “Audiences will enter Michael’s world . . . His work is inescapably about who he is: his lifestyle—real or imagined—his family, his interests and values,” writes Chris Saines in the press release. https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/media-release/michael-zavros-the-favourite-opens-at-goma-2023-06-23/

[10] Think, for example, of John Brack’s iconic Collins St, 5p.m. (1955), or the work of George Tooker.

[11] This is a narrative that builds upon previous interviews where Zavros has noted the ‘personal’ significance of the works via recounting, in absurdly minute detail, his childhood interest in fashion magazines. As quoted in Di Trocchio’s catalogue essay (“Guilty”, p.151).

[12] In a patriarchal bureaucratic society, is there a more generic image than a man in a suit?

[13] Noam Yuran, “Luxury and the Sexual Economy of Capitalism” Money in a Human Economy, Ed. Keith Hart, The Human Economy, Volume 5, New York: Berghahn, 2017. p.88. Yuran draws here on the work of Werner Sombart and Thorstein Veblen.

[14] Other examples of paintings featured in The Favourite that take luxurious interiors as their subject include POTSDAM INTERIOR/SAN SOUCI/SOMETIMES I JUST WANT TO BE MYSELF (2003), 1820s regency leather SOFA/Favela chair/Champion Dachshund ‘Windkiedach Wiggle’/a Dale Frank (2006), The Lioness (2010) and Body Lines (2011).

[15] A Private Collection: Artist’s Choice: Michael Zavros. South Brisbane: QAGOMA, 2013. The title pages of the catalogue make a note that the design of this ‘extends the fiction’ of the project, the only overt reference to the conceit.

[16] Ibid, p.16.

[17] And, indeed, Zavros figures that an ‘environmental’ reading might be one of the many readings people will want to ascribe to this work (McKay, p.41).

[18] Mercedes-Benz cars also appear in the works White Crash (2019) and Dad likes Mercedes (2020), both included in The Favourite.

[19] Chris Saines, “On Reflection: Zavros’ Bad Dad” Michael Zavros, p.27. Chris Saines, Foreword, Michael Zavros: The Favourite, p.18.

[20] Of course, Mercedes-Benz itself has already reappropriated this song, turning it against itself, and has used it in numerous advertising campaigns.

[21] See, for example, Zavros’ comments in an interview with McKay, where he ruminates on the memory of learning, after some major solo exhibitions many years ago, that people didn’t like him (McKay, p.38).

[22] I should emphasise that this work is not in The Favourite, but that its smaller, darker counterpart Sunbather (Small) 2015 is, a work which, even in its title, evokes it larger sibling painting. The monograph Michael Zavros (2017) includes large, detailed reproductions of this work which are a useful reference (p.17-19).

[23] Such as Bad dad (2013) and V12/Narcissus (2009).

[24] Robert Leonard, “Michael Zavros: Daddy’s Girl,” 2016. Available at: https://robertleonard.org/michael-zavros-daddys-girl/. Saines also notes the connection of Zavros’ Sunbather to Hockney’s Sunbather (“On Reflection” p.31).

[25] On this, see Ruby Awburn and Gillian Osmond, “Concept and execution: Michael Zavros’ materials and techniques.” Michael Zavros: The Favourite, p.115, 120.

[26] Leonard, “Michael Zavros: Daddy’s Girl.”

[27] Leonard’s catalogue essay remarks upon this, “As Zavros’ fame and fortune grew, his work seemed less aspirational, more autobiographical, illustrating the good life he could now afford to live.” (“The devil’s in the details” Michael Zavros: The Favourite, p.64). And this is regularly noted. For another example, see, Candida Baker, “Artist Michael Zavros and the power of the worst case scenario”, Sydney Morning Herald, Oct. 7, 2016. https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/artist-michael-zavros-and-the-power-of-the-worstcase-scenario-20160913-grfgje.html

[28] Butler, p.195.

[29] Leo Timmers, The Magical Life of Mr Renny, Trans. Bill Nagelkerke, Wellington: Gecko Press, 2012.

[30] It reminds me again of CJ Hendry, as the images of her work on her website usually include a shot of her arm holding a pencil, as if to prove they are drawings: https://cjhendrystudio.com/. The earlier Michael Zavros (2017) monograph also includes an unusual number of this type of image, but not to the degree of The Favourite catalogue.

[31] eX De Medici: Beautiful Wickedness, Brisbane: QAGOMA, 2023. p.43.

[32] In addition, the painting of a rose gifted to Rose bears strong resemblance to Magritte’s Le tombeau des lutteurs (1960) amongst other references to Magritte throughout the book.

[33] Michel Foucault, This Is Not a Pipe, Trans. James Harkness, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

[34] Ibid., p.44.

[35] Ibid., p.54.

[36] Leonard’s discussion of Zavros’ exhibition of paintings of Balenciaga handbags within a shop selling the same products, approaches this relationship in a similar way, noting that that there is no outside, only Zavros (“Charm Offensive”, p.75). Leonard returns again to this exhibition (of paintings of handbags) in his essay for The Favourite catalogue, writing that in this example we see that “reality and representation become interchangeable” (“The devil’s in the detail”, p.65).

[37] As Foucault writes as the final sentence of This Is Not a Pipe: “A day will come when, by means of similitude relayed indefinitely along the length of a series, the image itself, along with the name it bears, will lose its identity. Campbell, Campbell, Campbell, Campbell.” (p.54). In Zavros, however, the logic doesn’t diminish identity, but instead allows identity to be transferred across numerous self-referential products which refer to nothing beyond their own elevation as a brand. In a sense then, Foucault, writing in 1973, had perhaps not had the chance to recognise this similar logic in the work of Andy Warhol (to which his mention of ‘Campbell’ is a reference) and the elevation of Warhol as self-referential brand.

[38] https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/media-release/michael-zavros-the-favourite-opens-at-goma-2023-06-23/

[39] “On Reflection” p.26.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Devenport, p.43. Saines also notes the ‘baroque folly’ of the quickly-wilted flower arrangements (Foreword, p. 18).

[42] Certainly, there is nothing wrong with work that is macabre, though it is troubling when such work is understood as being an example of unremitting ‘beauty’.

[43] Butler and Lettau.

[44] As an undergraduate, Zavros had a side-hustle as a mural painter (see, Awburn and Osmond, p.111). [45] This work is a wall treatment that enlarges and is based on de Medici’s pen-and-ink and mica drawing Tooth and Claw (2009). The work is a response to the 2007 Nisour Square massacre in Baghdad, Iraq.

[46] Though relatively unusual within his oeuvre, Zavros has titled other works in relation to popular culture, such as Sideshow Bob (2015).

[47] McKay, p.41, and also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAmi4QnjJ8k.

[48] Le Corbusier, Toward an Architecture (1928), Trans. John Goodman, Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007. p,248.

[49] Ibid, p.231-51.

[50] Ibid.,p.247-48.

This week’s review was kindly Guest Edited by Lemonade writer, Kit Kriewaldt.

Kyle Weise is co-director of Kuiper Projects and the curator (exhibitions program) at Metro Arts.