Can you taste the human touch? Fully Automated Human Touch is a hybrid work combining choreography and installation by M@ Cornell and Merinda Davies that began as a disagreement between the collaborators. Is it possible to discern if your food has been made with love? Or is automation capable of meeting all of our (tangible and intangible) dietary needs? Fully Automated Human Touch is a meditation on this question, and the artists’ own Turing Test.

In Cornell and Davies’ shared universe it is 2083 and overlapping catastrophes of climate change and mass production capitalism have reached their dystopian depths. Responding to the 2067 fallout fuelled by food insecurity, all food is now manufactured via a completelymechanised chain of production—from seed to loaf, and stalk to stew—no human hand touches our meals until we consume them, alone. But in this closed system something might be absent, an elusive vitamin fortification that only human touch can offer.

This is the conceit of the work, which takes place in the subterranean laboratory of two scientists tasked with enriching food with Human Touch (or HT for short). This research is overseen by an omnipotent AI voice called ‘CAKE ‘, who directs experiments in a computerised monotone that echoes throughout the lab and collates experimental data via crystal contact points placed on the scientists’ bodies. As an audience we are invited into their laboratory, a white gallery with various installations made discreet through the use of translucent plastic sheeting. Stations for experiments are set throughout the space. On the walls, the fruits of their research are displayed: HT fortified food in its various vacuum-packed, dehydrated, and gel-capsuled forms are arranged in grid-like minimalism. Particularly effective and conceptually apt, in a knowing nod to Warhol’s Factory, is an installation of aluminium cheezel bags. Combined with warm atmospheric lighting, a pulsating drone-y soundtrack, and low-level theatrical haze, the effect is distinctly sci-fi. For audiences, entering the work is like boarding a spaceship or descending into a seed-vault.

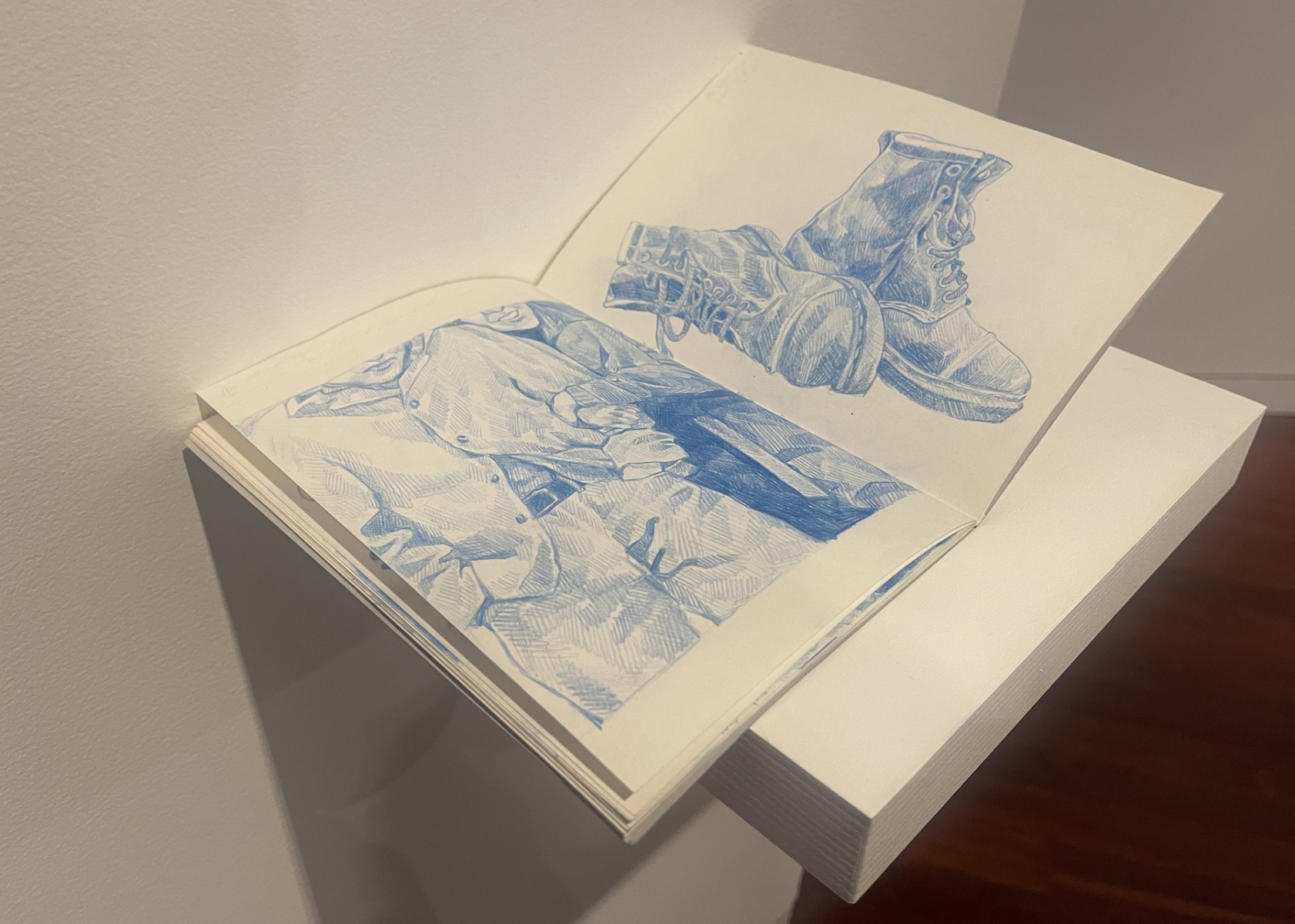

The performance takes place ‘in the round,’ we are welcomed into the lab as test subjects and anointed on the cheek with our own bio-data-harvesting crystal. Initially we roam the space, examining the installation details and watching a large-scale projection of food being hypnotically produced at-scale by machine production lines: fruit harvested, bread baked, dough extruded in endless cycles. We gradually become aware that Cornell and Davies are in the space with us, engaged in a choreography where they walk, eyes closed, through the lab and audience, tentatively slowly and magnetically drawing closer to one another. A tension is created between the pair, and their protective costume of plastic lab coats and safety glasses serves to offset the rare moments where they pause with curiosity and novelty at incidentalskin-to-skin contact.

The voice of CAKE often interrupts these moments of extra-curricular care and directs the scientists back to their work, where they inhabit the laboratory stations and perform various experiments to find the most effective path to HT+ enrichment (water is run down arms, code is written, cheezels are slipped onto fingers). The performance continues in this fashion, with task-based experiments directed by CAKE interspersed with more abstract moments of movement and physical connection. Most notable are the times where we, as audience ‘test subjects,’ are drawn into participation. A group recitation of the ‘Cheezel Rock Manifesto’ complete with chip-laden jazz hands (a lyrical re-interpretation of Eagle Rock), delivers a particular moment of levity that masks the darker core questions of this work. In fact, there is a troubling ease with which we readily acquiesce to the demands of the performance and literally drink the (HT fortified!) kool-aid as it is handed to us. Cornell and Davies exploit these power dynamics of the performance to savvy effect.

It is easy to see how the strange conditions and social anxieties produced by the pandemic give rise to a work that centres on human touch. However, the genesis of this work proceeds ideas of ‘social distancing’ and, to me, it feels more invested in critiquing our complicity with the endless horizontal integration of late-capitalism. Like all good sci fi, Fully Automated Human Touch has much to say about our current moment and the choices within it that we have. If we are inevitably moving toward a more automated and individualistic (touchless) future, this work reminds us of what creates meaning. It uses human connection to propel the work through its narrative: we are drawn to the moments of touch, the small instants when in between their tasks the two scientists explore the breadth of what contact can mean. But it also harnesses human connection on a meta-level; it created something real between us as audience members and Cornell and Davies as artists, a temporary accord that we used to navigate the performance together.

In the weeks after seeing Fully Automated Human Touch, my thoughts were drawn to time, and more specifically to what I spend my time on and how it makes me feel. If, in 2083, more and more of our needs are fulfilled by automation, how do we use those saved dividends of time? Do we make time for more work and productivity, or should we instead prioritise the pleasure of human connection. This performance doesn’t make its position clear, but rather cleverly acts to amplify our own existing beliefs. In the future, much like the present, meaningful fulfilment will come from where you seek it—and I will be finding it in the company of others (perhaps with a shared meal).

Tulleah Pearce is a curator and programmer with experience working with independent artists across Australia and the Asia Pacific to present and tour their works. Currently Assistant Director, Programs and Audience, at the IMA, Pearce has previously held roles at the Sydney Opera House, at Performance Space producing Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art, and has worked across the small-to-medium sector with roles at the Creative Practice Lab (UNSW), Blacktown Arts Centre, and Firstdraft.