Just across from the history-laden sandstone buildings that constitute the University of Queensland’s great court stands the UQ Art Museum. Bright, exciting, and enticing, the museum stands in striking contrast to the beige opposing it. The rich vibrancy of one of SUNA (Middle Ground) on its front lawn coupled with the eye-catching colours of Rosella Namok’s Old Girls Yarning into the Night (2024) makes the museum a difficult building to miss as you walk down Feeney Way.

Nor would you want to miss it, as UQ Art Museum has recently launched its latest exhibition, to come together as water. This exhibition – the latest instalment of UQ Art Museums Blue Assembly – reflects upon humanity’s ability to both create and destroy. Each work brings its unique sound to the symphony that is the exhibition at large. I will share my thoughts on a few pieces but nothing can substitute for the experience itself.

Instantly reminiscent of summer days spent in and around beachside rock pools, to come together as water, is an exhibition that does full justice to the incredibly diverse network of waterways that make up Australia – a level of diversity equally reflected in the mediums, themes and sensations on offer.

Megan Cope’s Whispers (poles) (2023) was a particular highlight for me. Walking past these oyster clusters, it was difficult for me not to rethink community through an ecological lens. To have the water fall away and come face to face with what lies beneath the waves is surreal, and it was in this detail that I found the time to reflect on my own communities, and my own ties to the water.

The multimodal experience of YOYI (2020) caused me to feel a sense of homesickness for places that I have never been, for waterways I have never swum in, and for beaches I will never step foot upon. to come together as water is both a beautiful celebration of the water, and a call to arms for all of us to band together and protect these special places before we watch them fall to ruin at the hands of humanity.

It is difficult to look upon Heather Koowootha’s Ngak Yangka (2021) and not feel like these waterways are immortal. Just as it is equally difficult to look upon Solomon Booth’s works and realise that, in our current age, they unfortunately are not.

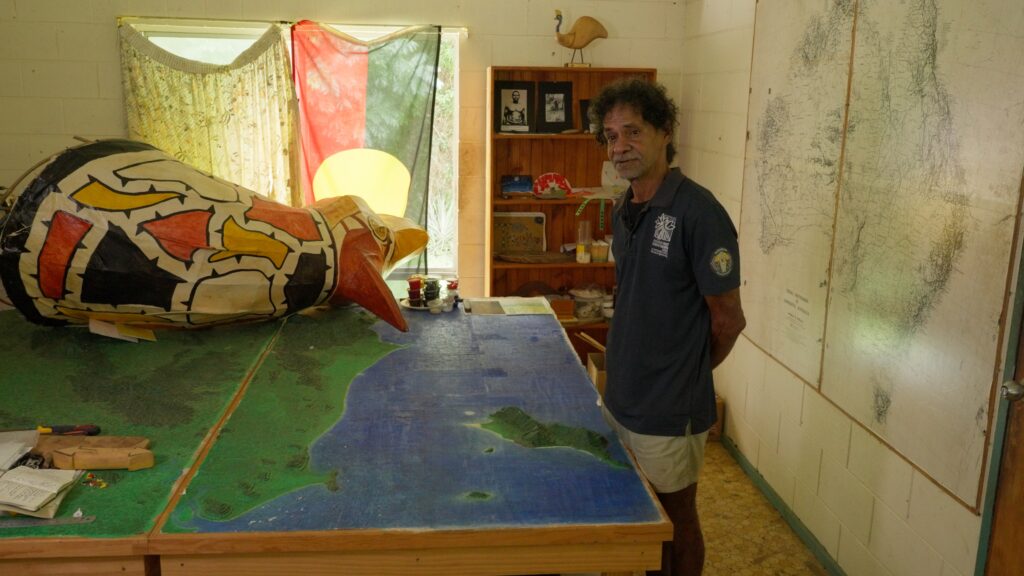

There is no work in the museum that will make you as keenly aware of our current waterway predicaments as Rachel O’Reilly’sfilm, NORTHERN WATERS. If to come together as water draws you in with the beauty of our waterways, NORTHERN WATERS strikes with urgency. Its exploration of the complex timelines surrounding our reefs is illuminating. And if you are able to watch the experimental film in full, it is difficult to come away without feeling simultaneously upset, hopeful, and informed.

Shot beautifully in locations across North Queensland, the film illuminates the hard work that has been going on for centuries as First Nations people took and continue to take care of the natural world around them. The film dives into the more recent struggles to get this work officially recognised by modern government officials, with particular emphasis on the aftermath of the 1960s ‘Save the Reef’ campaign. The full film is 103 minutes long and well worth the time spent watching, especially if you have ever had the basic human instinct to reconnect with nature and wish to ensure that future generations are able to have that same experience.

In the first Australian exhibition by Swedish artist Petra Bauer, WE CALL YOU! Sisters! Mothers! Workers! is an exploration of feminism and community. Through the use of long, uninterrupted takes depicting domestic tasks in their films, Bauer seems to invite viewers to reflect on what they themselves have witnessed in these seemingly mundane moments and to engage on a level that is so close to home it practically has walls around it.

The works left me with a simmering feeling of resistance. It demonstrates that protest does not necessarily have to mean demonstrations in the street; resistance can be just as powerful in the everyday as it is in the extravagant. The pieces and films look to reframe power through the lens of the ordinary. Although Bauer’s work may not initially seem closely related to the other collections, it too invites you to reflect on your everyday connections to the world around you.

Created to represent the traditional raun haus (round houses found in the highlands of Papua New Guinea), SUNA (Middle Ground) is perhaps one of the most peaceful buildings that I have ever had the pleasure to step inside. Although I cannot speak for butterflies, I would be more than willing to hazard a guess that being within SUNA is a very similar feeling to that of a cocoon.

Despite its scale and bright colouring on the outside, once you have been within the installation, it is difficult to imagine that it has not always existed in this place. It’s a feeling so pure that if someone were to ask me if SUNA had always stood on the lawn of the museum, I would immediately say yes (despite having walked past an empty lawn hundreds of times beforehand).

Upon taking off your shoes and entering, there is no doubting that you are safe, warm, protected. The light calls of birdsong place you hundreds of kilometres away, and there is a peculiar sense of serenity. If you are to visit the new range of exhibits at UQ Art Museum, I would personally recommend SUNA (Middle Ground) being both your first and last stop on your tour. As a space for contemplation, I think you would be hard-pressed to find anywhere better on the busy campus that is the University of Queensland.

Alex Cooper-Williams is an emerging museum professional and writer living and working on Jagera and Turrbal land.