Standing in the cavernous, antiquated, industrial space of White Bay Power Station, curators Cosmin Costinaş and Inti Guerrero introduced an extraordinary vision for Ten Thousand Suns, this years’ iteration of the expansive and long-running Biennale of Sydney. The exhibition, in their words, promises to share the multiplicity of experiences—across time, space, and language—of the singular, shared sun of our world; to highlight our inevitable path amidst toward a scorching planet; and to metaphorically suggest solar radiance by showcasing Indigenous, carnivalesque joy. In turn, the exhibition addresses the harsh realities of colonialism, climate change, and capitalism directly, with neither fear nor anxiety about our future, but instead with wit, criticality and resilience.

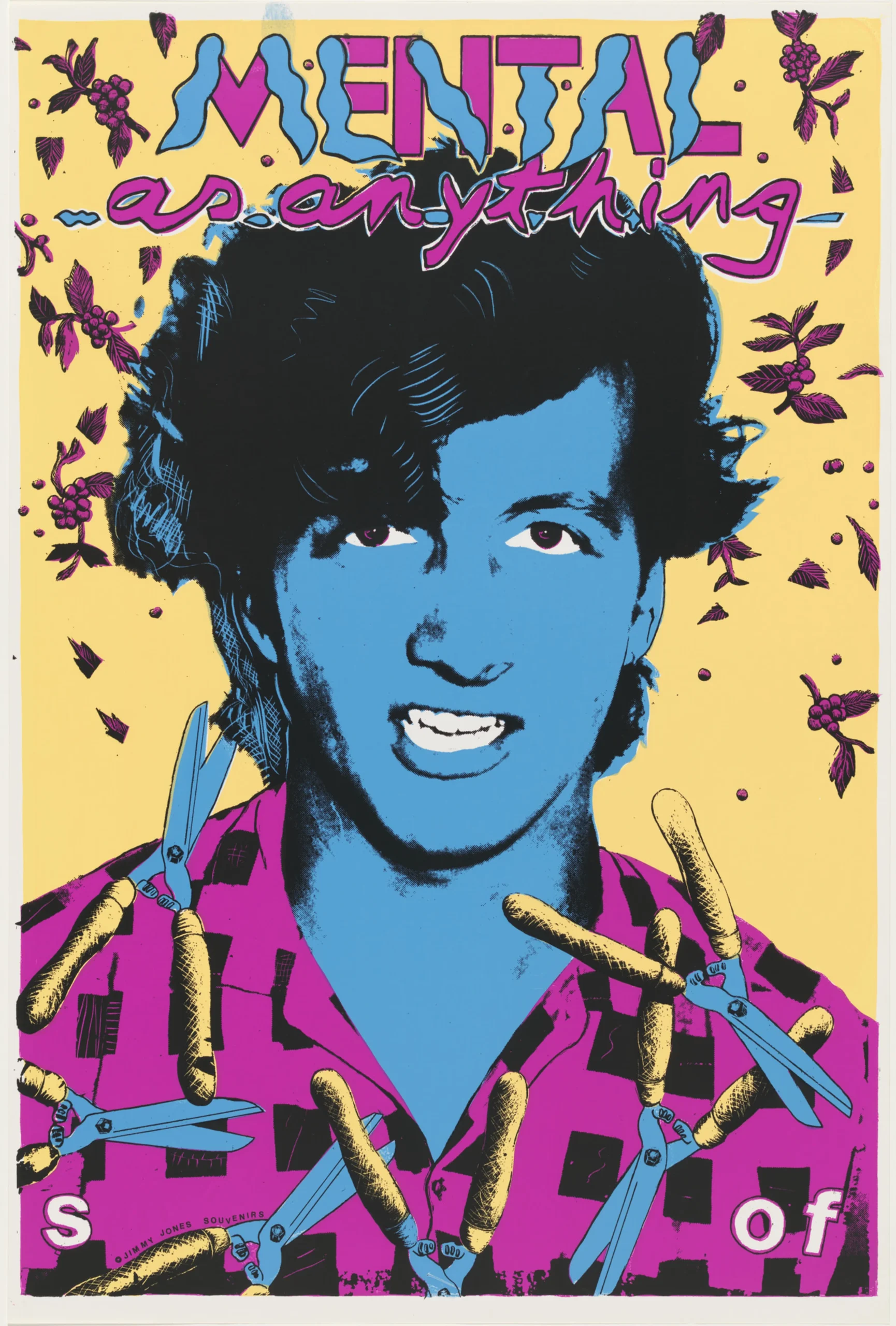

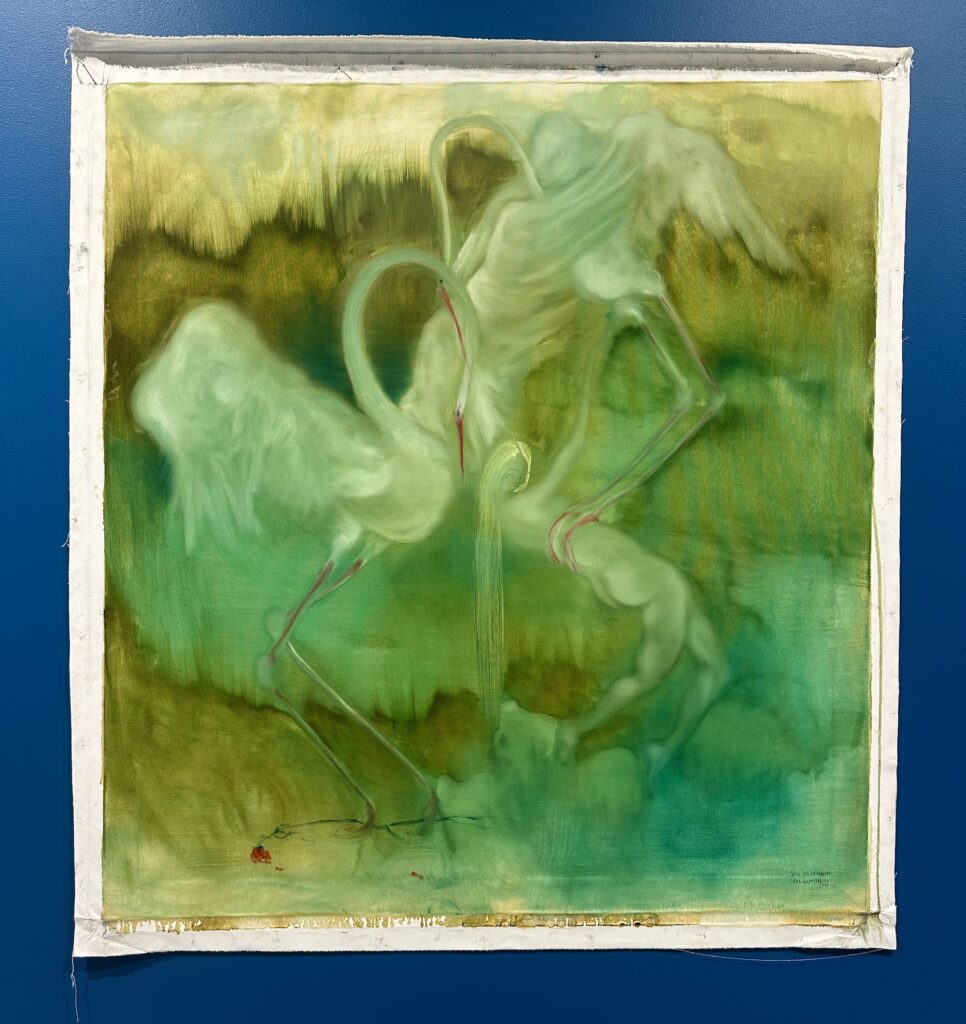

White Bay is the newest of this years’ 7 venues and the most spectacular, allowing for multi-story works (Dylan Mooney and Eric-Paul Riege), oversized digital screens (Özgür Kar), and print works re-imagined as carvings in the venues’ walls (Darrell Sibasado). The most successfully staged works were integrated into or otherwise layered with and juxtaposed against the strange and compelling spaces of the building. These include Destiny Deacon’s cut-out photographs of black dolls pasted onto a set of small, gridded, interior windows; Felix de Rooy’s trippy collages hung amongst machinery; Andrew Thomas Huang’s Mother of the West—a gigantic, jade-blue face fashioned from steel and automotive paint, its decorative hair and jewellery at odds with the geometric, hyper-functionality of the power station—and Marie-Claire Messouma Manlanbien’s shimmering, detailed textiles somewhat hidden, and made all the more enticing, behind glass, this time in conversation with the operational mechanisms of the site. Further highlights at the site include the luscious beauty of Satch Hoyt’s semi-abstract, semi-figurative paintings; the joy of Kaylene Whiskey; and a suite of black-and-white photographs of Indigenous figures in a field, equally familiar and unfamiliar.

Moving through consecutive venues, stories begun at White Bay continue. Doreen Chapman’s paintings, for example, punctuate the Biennale. Her works appear at every additional venue, often near the entry. I imagine this as a physical manifestation of the credence: “First Nations First.” These are beautiful works, deftly coloured, painting images of Chapman’s life on the edge of the “sandy desert, in the Pilbara region.” At Artspace hangs a second soft-sculptural pillar by Riege and at Chau Chak Wing (CCW) we encounter a 1988 photograph of Malcolm Cole, the same figure celebrated in Mooney’s epic portrait as well as further black-and-white photographs, revealed here to be of the predecessors to Bangara documented by widely-adored photographer, William Yang (who extended this doubling by appearing in person at multiple events across the opening week). Bonita Ely, Mangala Bai Maravi, and Juan Davila also number among the artists whose works were shown at multiple sites. The Biennale, by virtue of its size, is typically exhausting. By contrast these repetitions provide a welcome mental pause.

Ten Thousand Suns continues the turn to textiles and craft familiar to many recent Biennales. Rather surprisingly, however, video was a quiet hero of the show. Unlike previous Biennales, which seemed intent on using video as a filler, especially across the vast footprint of Cockatoo Island, here video was curated sparsely and most often via short works. In one by Iratxe Jaio & Klaas Van Gorkum, unseen figures shout descriptive phrases from Picasso’s Guernica to the present-day Basque landscape of Picasso’s painting. In another by Agnieszka Polska, a teenage boy travels a haunted landscape, compelled by a talking crow.

Figurative painting is also well represented, replacing immersive, participatory, hyper-restrained and conceptual, or messier, detritus/found-object art forms with this foundational mode. I was drawn to Sana Shahmuradova Tanska’s oil paintings at Artspace. Her liquid-esque bodies—dancing, melting, on fire, and hazy with gas or smoke-–appear dreamlike and surreal, otherworldly. But closer looking, and reading, reveals their very Earth-bound circumstances. The Ukrainian artists’ paintings witness events in the Ukraine. In the curators’ words, they offer a means for her to make sense of atrocity. At the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Oaxacan artist Francisco Toledo equally caught my eye. Two of his small works in particular, Self-portrait with Grasshopper (1989) and Muerte con Sapo (Death with Toad) (1989) are striking for their liveliness. Further works by Toledo commemorate very real and recent events, such as the 43 (a group of abducted Mexican students), and belong to a powerful thread of commemoration within the Biennale.

Costinaş and Guerrero locate Toledo within a still-to-be written history of Indigenous modernism. Indeed, First Nations artists and artworks are highly visible throughout the exhibition. Visiting from Meanjin/Brisbane, it was heartening to see so many Queensland artists among this cohort, no doubt due to the curatorial voices of Meanjin-based artist Tony Albert, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain First Nations Curatorial Fellow, and once-Meanjin-based curator Vivian Ziherl, Curatorial Advisor. Rounding out the local artists already mentioned are Megan Cope’s colonial-style map reinscribed with Indigenous place names and shimmering against a golden gallery wall; Gordon Hookey’s proliferating kangaroos within a room of works exploring the colonialism of nuclear testing, and Tracey Moffatt & Gary Hillberg’s filmic montage of Hollywood disaster scenes amidst further works on real and imagined apocalypses.

Ten Thousand Suns is a humble Biennale. In place of must-see artworks and artists operating at the height of international success, it offers smaller, hyper-regional, and little known stories, often recollecting narratives of cross-cultural connection and using art as an illustrative device for accounts found in the archives. Indeed, the storytelling of the exhibition is so strong that special note must be made of the wall texts, which provide exemplary context and are equally enlightening and accessible. But this storytelling at the micro-level operates at a cost.

I imagine Costinaş and Guerrero thoroughly enjoyed their time during the research phase of the exhibition, discovering small works made by “once known child artists,” remembering artists who have died, and extending their thematic into unexpected and tangential forms. I can’t help but feel, however, that they lingered here too long; that they failed to sufficiently turn their attention to the macro story they were creating when drawing these selected works into the larger curatorial conversation of Ten Thousand Suns. Even moreso, it seems to me that in these tangential narratives the curators let slip the material, embodied, experience of the audience; that in lingering in the realm of storytelling this Biennale curiously decentres the art. This shift from the art to stories about the art is felt most keenly in artist reproductions: a wall decal of Albert Namatjira stands in for a painting by the artist, huge prints of VNS Matrix’ germinal works at White Bay lose something of the digital glitch and material decay of their earlier forms.

Despite my criticism, on the scale of individual artworks Ten Thousand Suns is equally moving, compelling, and uplifting. Most significantly, it roams with ease across the temporalities of past, present, and future, eschewing the tendency for Biennales to focus on contemporary practice in favour of mining the archive as it resonates with this moment. The result is an exhibition squarely directed toward the future, seeking to prepare, activate, and propel us to a better tomorrow.

Louise R Mayhew is an Australian Feminist Art Historian and the Founding Editor of Lemonade.