My visit to Suspended Moment coincided with a talk between artist Frances Barrett and curator Daniel Mudie Cunningham. The pair described their process of responding to the archive of Katthy Cavaliere, an Italian-born Australian installation and performance artist, whose life was cut short tragically in 2012. They used the word ‘communion’ multiple times; the theme also features heavily throughout Suspended Moment. It aptly describes both instances of ritualistic exchange and camaraderie felt in the exhibition, which posthumously showcases Cavaliere’s work alongside work by the three recipients—Frances Barrett, Sally Rees and Giselle Stanborough—of Suspended Moment: The Katthy Cavaliere Fellowship.1 Established in Cavaliere’s name and supported by her estate, the generous $100,000 fellowships support the creation of new work at the “nexus of performance and installation.” The artists first exhibited their fellowship outcomes individually, at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (Barrett); Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart (Rees); and Carriageworks, Sydney (Stanborough). Now, their monumental displays have been synthesised into a touring exhibition, which recently passed its halfway point.

Entering the space, I first encounter Gateway for the Witness (2020) by Rees. The work is a component of her larger installation CRONE (2020). Two blinking eyes are positioned soundlessly on a two-channel video. They stare relentlessly, appearing to penetrate beyond the doors to the gallery. The eyes are overlayed with fractured stop motion watercolour imagery displaying geysers of water spurting from phallic structures. By contrast, the eyes are unnamed and bodiless; nevertheless they pierce and interrogate.

From this instant, I sense that Suspended Moment is internally reflective and externally critical. Rees describes her artwork as an ‘effigy’ for how she wishes to be perceived as she ages, with ‘crone’ being a word to aspire to rather than reject. Rees’ entry artwork connects to Flock (2020), which is displayed at the rear of the first gallery. For this 17-channel video, the artist called upon her fellow ‘crones.’ She filmed her mother, friends, and colleagues wearing prosthetic witches’ noses before overlaying the videos with intermittent bird calls and hand-painted animations that correlate visually with Gateway for the Witness. Despite the ageist socio-political reality within which Rees’ work emerges, she is humorous and subversive in her artistic ‘communion.’ She finds emancipation from paternalistic scrutiny within her coven of mature women.

Rees’ work shares space with Barrett’s video, A Song for Katthy (2022), and the complementary poem, A Song for Katthy (Notation 1 & 2) (2022), both of which are from Barrett’s larger series Meatus (2022). The two artists connect conceptually through their discrete yet highly collaborative approaches. In Barrett’s video, I recall panting, pushing, clutching, growling, and slurping. The vocalist is guttural, surrounded by red lighting and a film crew that move with and against their stationary figure, reacting only to the reverberations of voice. Singing is not the right word. Occasionally, the vocalist glances down, stealing looks at a composition drafted by Barrett, who is behind the scenes splicing together the roles of dramaturg, composer, poet, and performance artist. Despite its layered and sometimes audibly muffled nature, Barrett’s work is clear and generous in its dialogue with the writing and performance documentation left by Cavaliere. Barrett’s reverence for the late artist’s archive of diaries is undeniable and coalesces with her sound and movement based practice.

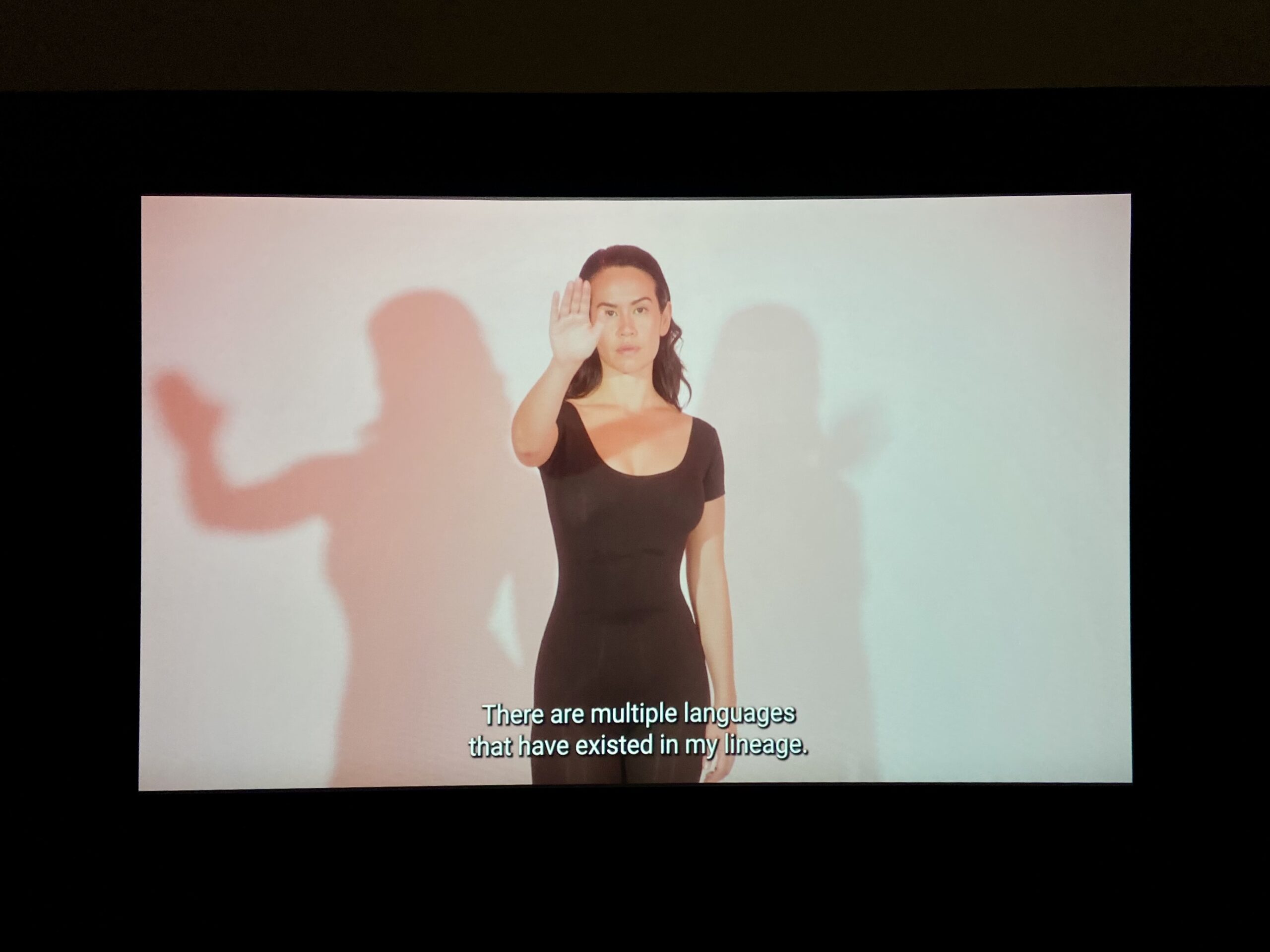

Moving to the second gallery, I meet Stanborough’s contribution: four artworks based around a ‘cinopticon.’ This is the artist’s take on Michel Foucault’s disciplinary institution of the panopticon. Stanborough’s installation uses video, sound, wall drawings, and sculpture to illuminate the modern collapse of personal and public life. In this part of the gallery, reflection and modes of surveillance are encountered in varying ways. A mirrored digital surface obscures body parts that open and close, while large black circles of paper with contrasting white writing (similar to blackboard algorithms) and a gaping sculptural well all draw me closer and lead me, almost subconsciously, about the room.

Both Stanborough’s installation and neighbouring works by Cavaliere—a moment alone (1998), transient collage (2000), and automatic actions (2000)—sit at the threshold of personal space and form a salient curatorial choice. The latter three highlight Cavaliere’s dedication to ‘making sense’ through ‘making public,’ using repetitive personal disclosures, artistic intuition and streams of consciousness as tools.

I am purposefully not covering the life and work of Cavaliere in this review. She was undoubtedly a brilliant artist whose impact has been lovingly captured by friend and curator Mudie Cunningham in the immense publication Katthy Cavaliere (2016).2 I encourage accessing this book to learn more about Cavaliere’s tumultuous, bourgeoning, and unfortunately short life. Within, Mudie Cunningham brings to light a journal entry from Cavaliere where she writes: “’When I was a child I wondered what it would be like to meet everyone in the whole world.”3 Though an ambitious goal, through this touring exhibition Cavaliere has reached new audiences across Australia; through her estate and the new work by Barrett, Rees and Stanborough, her enthusiasm for installation and performance has found new vessels; and through Mudie Cunningham’s curation, the world of Cavaliere will continue to unravel. Suspended Moment is a testament to the impact of one person, the possibility of delving deep into the self, and the importance of artistic communion.

Redcliffe Art Gallery is the only Queensland venue for Suspended Moment before it continues to Araluen Arts Centre, Maitland Regional Art Gallery, and Goulburn Regional Art Gallery.

1. https://katthycavaliere.com.au/fellowship/

2. https://katthycavaliere.com.au/

3. Katthy Cavaliere, diary entry, 7 December 2000, as quoted in Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Katthy Cavaliere (Tasmania: Brown paper with the Museum of Old and New Art, 2016).

Madeline Brewer is a curator and program producer. She works on Dungibara Country in Toogoolawah.