One of the first things Christine Clark, Head of Curatorial and Collections, said as she led us through this exhibition was how “obvious” the theme of flowers is. And yet, almost no-one seemed to take the plunge into curating a whole show about them. It made me realise how much we overthink art.

A lot of the time I go to art shows waiting to be introduced to a new concept or idea, with artists itching to be the first to dream something up and show it to the masses. Flowers aren’t new, and are one of the first things anyone in childhood (artist or not) attempts to draw: with bubble petals and a smiley face in the pistil, a little sun sits in the corner of the page. It was nice to be taken back to the basics —in terms of artistic subject—in this exhibition; while also being introduced to new ways that artists express their love for foliage.

The exhibition is set out to honour the works’ different interpretations of flowers: the softer, more traditional paintings sat together in the first room, and as the show expanded, brighter and more abstract works were drawn into the mix. Further toward the end, ceramics, crochet, and other crafted pieces scattered the room, demanding their own space and attention. In this section, I felt as though I could really focus on the work in front of me, without being too distracted by other pieces.

We started off in the smaller, lower lighting foyer-like room adorned with traditional approaches to the flower. I was drawn to a stained glass daffodil, physically embedded into the wall as a window in the room. The curator introduced the artist as Julian Podmore, a Welshman now living and creating here in Meanjin. I nodded to myself, the Welsh love our national emblems that’s for sure, and my fresh leek tattoo agreed.

A close portrait of a pink snapdragon, by John Honeywill, also stood out. It was painted like a headshot; no fancy background, just a white plane. I wanted to get to know the snapdragon personally. John stepped forward and confessed he tries to evoke a sense of poetry in his paintings, which was so clear the longer I looked at his painting. It was intimate, like his own personal love letter to the flower he was studying.

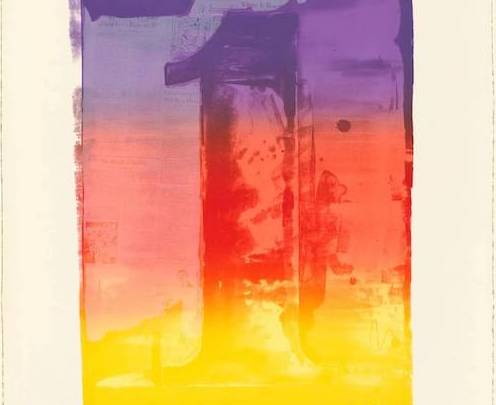

To get to the next part of the show we wove through the absolute feat of an art experiment by Karen Stone. Large sheets, which at first I assumed were paper with spray painted designs, were in fact a culmination of Karen’s pre-loved clothes transformed into “painted paper.” Karen pummels the colours out of the fabrics to create coloured pulpy liquid, which she lays down again and again to create huge and layered works. The final pieces are like your grandma’s best table cloth, only brought out on birthdays, with royal pink and red flowers against bone white backgrounds.

In Christine’s words, we were then taken “through the Queenslander, and then out to the garden.” Facets of the traditional Queensland home, which I love so much that I depict them in my own art, were present here, like white timber sub-floor batten screens, designed to keep hot houses cool. Decorative archways guided us through the entire exhibition, and the hardwood floors didn’t squeak as I expected. I had to remember I was not, in fact, in an actual Queenslander.

From the shelter of the home we popped out into a larger room with much bigger painted pieces than the first section. Here, Ashlee Becks’ highly textured Flower Quilt demanded attention with thick paint strokes that mimic rippling fabric. Ashlee’s work is deeply personal, according to her, and I gained a sense of comfort from her painting. Had it not been mounted on the wall, I think I would have tried to envelop myself in it, which speaks to Ashlee’s ability to convey texture and feeling through paint. Monica Rohen’s trio of works were comparatively claustrophobic. They can only be described as an aesthetically-pleasing nightmare. Each focused on a different flower with the flora completely consuming a human subject. Monica stated the sense of encroachment was intentional, with the foliage she picked thick enough to leave no blank spaces in her work.

Then Milomirka ‘Milly’ Radovic’s crochet came into view and the crowd flocked to look at the detail of this work up close; a curtain of warm flowers adorned the wall like a garland. Milly described herself as not an “artist” but rather a “crafter,” telling us how culturally normal it was for Serbian women in her village to crochet and knit. Making this work, she humbly told us, equalled what she was raised and taught to do. I hope she doesn’t mind that I consider her an artist.

Lastly we were met with unique installations ranging from Sarah Rayner’s porcelain white ceramic vegetation, splayed out behind glass like skeletal remains, to Boneta-Marie Mabo’s critique of colonial Australia in the form of seed packets, each beautifully-designed sachet made to represent a different oppressive girls’ school. Boneta-Marie’s work successfully comments on the objectification of young Indigenous girls through the medium of objects themselves, it’s ironic and also harrowing.

From the 27 artists displayed in Rearranged: Art of the Flower, it was hard to narrow down stand-outs to talk about here because each artist brought something unique to the table. Although we’ve ‘done’ flowers before, I don’t think that means we’ve seen it all. Perhaps there is an inherent overlooking of flowers as a subject due to their ‘feminine’ nature. I’m glad that the Museum of Brisbane chose this theme and curated the space so the audience can soak in each of the works of art. The layout was immersive and I will be revisiting soon to gain a longer look at each of these meticulous and thoughtful homages to the flower.

Charlie Maycraft is a writer and artist living in South Brisbane. They are a regular columnist at A Modern Gays Guide, where you can find their queer film and book reviews every month.