What does it mean to occupy? Who and what can be occupied? A place? A mindset? A people?

These are the questions raised by OCCUPY: The Exhibition. Nestled into the intimate confines of Vacant Assembly, OCCUPY frames the physical, cultural, social, mental and political inferences of its title word via an interdisciplinary lens. Initiated by the 2022 Australasian Students of Architecture Congress (ASAC), curator Taylor Hall had the big task of negotiating the plethora of media, practice, theory and perspectives of artists George Goodnow, Claire Grant & Kuweni Dias Mendis, James Hornsby and Lillian Whitaker into a cohesive show.

The Occupy Movement looms over this exhibition, yet that connection doesn’t seem to have been approached by ASAC’s coordinating committee. A call for real democracy, if such a thing exists, is at the centre of my interpretation of ‘occupy.’ Like the movement, OCCUPY: The Exhibition relied heavily on social media to communicate its message. I question whether social media is a democratic space. How do algorithms and promoted content impact the way that information is targeted to an audience? How does occupation of the virtual space implicate ASAC’s end goal, according to their website, of instigating agonism?

Upon entry to Vacant Assembly, a communal word search covered a table. Inviting attendees to locate words like ‘provocation’, ‘anti-establishment’, ‘celebration’ and ‘conformism’, OCCUPY: The Word Search and its innate difficulty (no, seriously, it was really hard) forced individuals to truly consider these terms in and out of their intended contexts. By situating this puzzle near the entrance, the audience was informed by these terms as they explored the artists’ work. Each of the five artists practice in a different medium and addressed the term ‘occupy’ in a unique way.

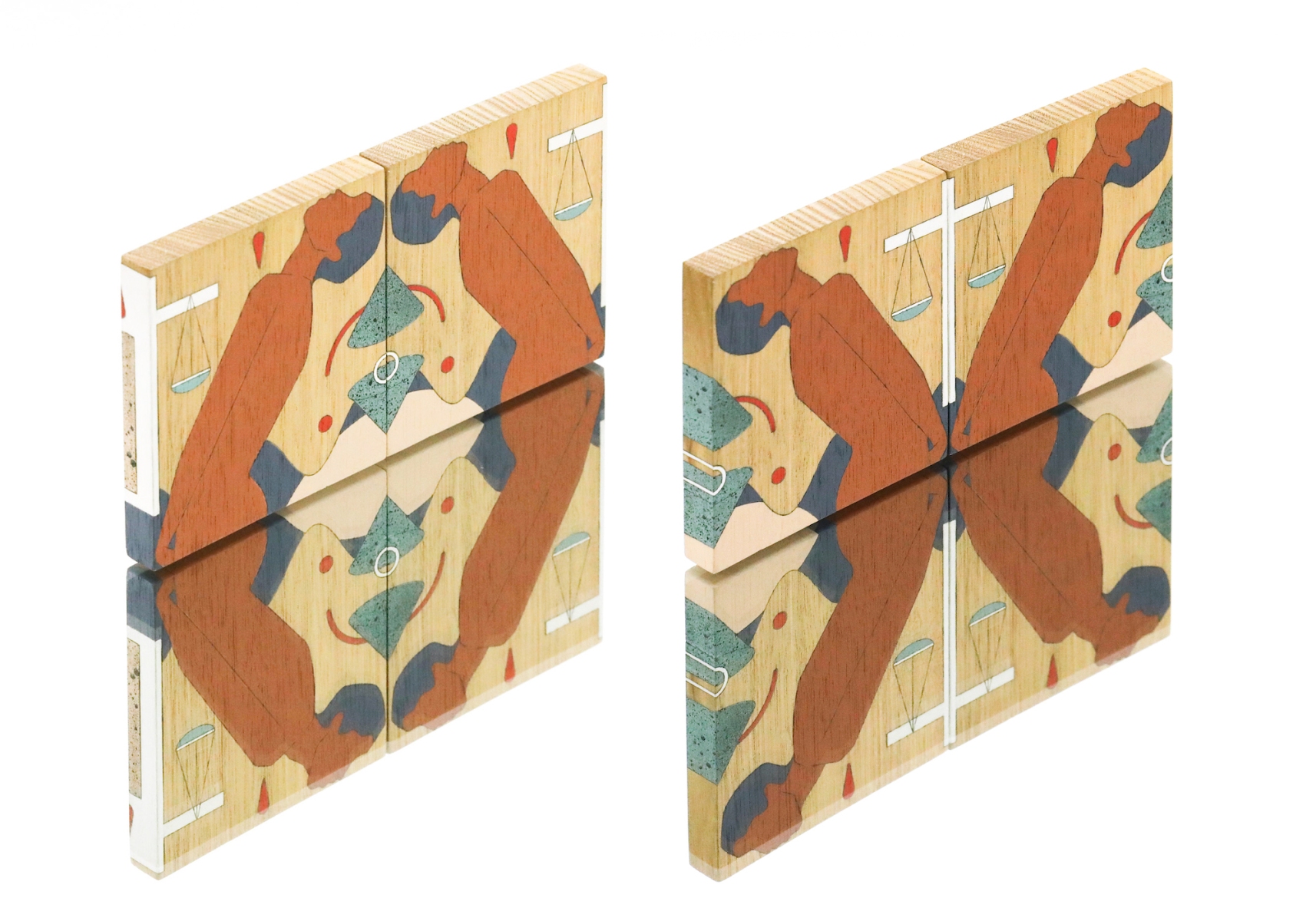

George Goodnow reimagines architecture to alter public perspectives of place. Goodnow’s installation, Merge (2022) fuses soft and strong forms, framing Vacant Assembly’s industrial architecture with the illusion of softly draped fabric. This is revealed (only when I looked closer at the floor chart) as acrylic on canvas and aluminium. Subsequently, Goodnow investigates the relationship between space and objects, occupying a moment somewhere between organic and inorganic matter.

Collaborators Claire Grant and Kuweni Dias Mendis peel back memories of a place and the symbiosis (or lack thereof) between humans and the natural environment. Their collaborative cyanotype map, Heart of the River (2021), is large. It demands attention and requires the viewer to look closer at the intricate strokes of pastel and stitched 24-karat gold to uncover an alternate map of the Brisbane River. Each stitch feels forceful yet delicate. One may consider the controlled force required in a stitch as equal to the force of the river when nature takes control and Brisbane floods, once again. The notion of occupying this space (Meanjin) is problematised. Can anyone control this place? A place that continues to be occupied by the whims of nature?

Lillian Whittaker’s Co-existing Pollinators (2021), Field Notes (2022), and Ritual Collaboration (2022) presents life from the perspective of non-human beings, in this case, European honeybees. Whittaker has created wax art objects that may expand a hive. The artist presents them to an established bee colony and, if they accept it, they become part of their hive. A partnership between artist and bee is formed; the two collaborate on adaptive wax forms, a mere handheld object to a human, yet a sizable site in which to live, work and feed, for the honeybee. Whittaker temporarily suspends the mutually-made sculptural works within the walls of Vacant Assembly alongside textual observations taken throughout her field research.

James Hornsby’s unmissable and vibrant Neo-Expressionist painting, Yucky Man (2022) fractured the space. Hornsby’s fluorescent colour and vertically thrusting canvas melds reality and nightmare, presenting an abstract face with chillingly empty eyes. This surreal experience is furthered in the adjacent work, Magic Carpet (2018–2022). Pairing what looks like a Persian carpet with fluorescent light strips that glow from underneath, this work manipulates fabric and light to create the ultimate Aladdin-esque reference. Hornsby presents an unapologetic occupation of space, both in the vertical crescendo of Yucky Man and in the central, unavoidable presence of Magic Carpet positioned squarely on Vacant Assembly’s floor.

The collaboration between the ASAC committee, curator and artists is evident throughout the exhibition. The accompanying catalogue included a prompt for the audience to respond to at a later time. This was a clever choice by the coordinators, extending the reach of OCCUPY: The Exhibition beyond its mere three-day run.

Occupy: The Exhibition was only one chapter of ASAC’s congress, situating particular voices within an established artspace. I am curious about how viewing these works would have been impacted if they had been presented in a public space, rather than among the great narratives of art galleries and museums.

Ultimately, this collection of works were individually and collectively striking. The interdisciplinary approaches, encompassing architecture, art history, fine art and field research, were equally interesting.

Olivia Trenorden is an artworker and researcher living and working on Yorta Yorta land (Shepparton, Victoria). She is passionate about art institutions as sites for community to gather, to learn and as public spaces. She holds a Bachelor of Arts (Art History) (Honours) and is currently completing her Masters of Philosophy at the University of Queensland. Olivia is especially passionate about the way that Artist-Run Initiatives construct strong arts ecologies. She has worked at the Shepparton Art Museum, Outer Space, University of Queensland Art Museum and Ipswich Art Gallery.