How can we confront colonialism’s ongoing legacy and truly learn from the past? To be aware of history is to recognise the roots of injustice and, unfortunately, many Australians do not care about injustice until it becomes personally relevant.

Nathanael Edwards is an emerging artist belonging to the Dulgubarra, Bagirbarra, and Dyiribara clans of the MaMu Nation. His involvement in the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair was a memorable one, with HEAR NO, SEE NO, SPEAK NO, a photographic exhibition that reflected the historical tragedy of systemic violence towards First Nations people in Australia.

Being the first time Edwards had explored the medium of photography, he was taught onsite by Dutch-Filipino photographer Phil Schouteten, who has a distinctive career creating meaningful storytelling through photography. Often travelling through Cape York, the Torres Strait and throughout Queensland, Schouteten has embodied relationality with many different communities, including Nathanael’s. In a conversation with this reviewer, Schouteten describes Nathanael as “incredibly passionate about truth-telling and expressing that through his art.”

With a total of twenty-one photographs structured as solo portraits, diptychs, and six composed triptychs, the astute use of semiotics and language enables diverse discussions around truth-telling to emerge.

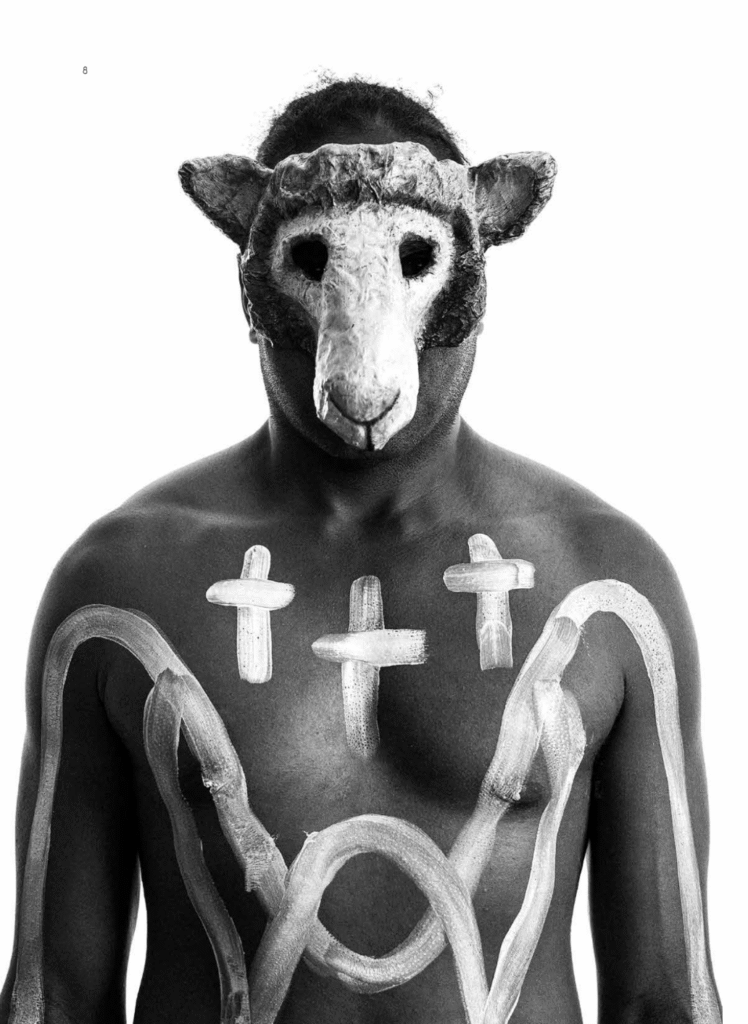

The exhibition provokes thought without hostility as viewers are immediately met with large-scale, black-and-white framed photographs. The curatorial intention facilitates a compelling and meaningful dialogue. The photographs’ white background merges with the gallery’s white walls, heightening the visual impact of the subject’s dark skin. The use of white within additional accoutrements further contextualises the deliberate use of this grayscale.

An Aboriginal man is featured within each photograph, adorned with distinctive items conceptualising and connecting to historically relevant discussions. The series itself investigates the objectification of the black body within photography, serving as a historic reminder of the anthropological relationship the medium has with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The obscurity of the individual’s face positions the viewer at a relational distance, the only repetitive representation of his identity being his black skin and body paint. The significance of the symbolism can only be completely understood by those of the MaMu nation, demonstrating the tenacity and complexity of both cultural and social responsibility. Through conversation with Edwards, it was discovered that the paint-up is a Sacred Men’s symbol, further reiterating the intricacies of roles within community.

The use of acrylic paint highlights the relationship between culture and accessibility. To establish cultural continuity within the contemporary landscape we must understand that culture is ever-changing and resilient. It is not the paint that makes the symbol Sacred, it is Moiety, Lore and the reference of relation in which the symbol represents.

Edwards categorises the numerous series through notable proverbs to platform complex discussions Australia attempts to avoid. This deliberate positioning of language can be seen in artworks such as Elephant in the Room, Like Lambs to the Slaughter, as well as the triptych, Hear No, See No, Speak No. The power of language is indisputably recognised, as Edwards uses the familiarity of these terms to relate to the viewer.

Like Lambs to the Slaughter discusses the harrowing legacy of religious missions and the indoctrination of First Nations people. The vilification of Indigenous culture was just one of the many tactics used to justify the systems of control under the guise of salvation.[1] The three crucifixes referencing the death of Jesus Christ articulate the inherent morality that can encompass power achieved through greed. Jesus died, judged as a criminal, communicating the perseverance of perspective and the comfort of privilege when those who rebel are ridiculed for opposing the majority.

Further expanding on these systems of control is the titular series Hear No, See No, Speak No, as well as “Act, Think, Be.” Both triptychs acknowledge the realities of forced assimilation, highlighting the subjugation of language and cultural practices. Australia has a rich history of silencing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in hopes of diminishing Indigenous identities. By confronting this continued systemic violence, Edwards enables viewers to reflect on their positioning and contributions to the dynamics of race within this country.

Edwards thoughtfully engages with the multifaceted natures of these prejudices, exposing the various ways they unfold before the viewer. In the image of God – Godless nation, the alarming rates of casual racism within Australian sports are highlighted through the representation of athletes Adam Goodes and Latrell Mitchell. As the only diptych within the exhibition, both portraits feature the recurring Men’s Symbol alongside each player’s jersey number and their team’s representative mascot — the Sydney Swans and the Rabbitohs.

The title of the diptych references Genesis 1:27, “So God created man in His own image”, ultimately highlighting the hypocrisy of a society that claims equality, whilst dehumanising its First Nations peoples.[2] Both Goodes and Mitchell have been ridiculed for standing up against the racism they have endured. Edwards positions the viewer to reflect on how level the playing field truly is when First Nations athletes face such discrimination within their professions.

Simultaneously, the recurrence of white hoods functions as a symbol of racial hierarchy and systemic dominance. Edwards confronts white supremacy by using symbols of power, such as the Crown and the Union Jack, to name and shame the perpetrators of these discriminatory systems. Under One Flag Divided We Stand acknowledges the current division of Australian society. It is through the individualistic Western concept of success, which justifies greed at the expense of those wrongfully perceived as less than.

HEAR NO, SEE NO, SPEAK NO by Nathanael Edwards excels as a catalyst for reflection and conversation. In the context of ‘Pay Attention’, Edwards provides a spotlight to the very real issues within Australia. His astute use of both language and semiotics positions the viewer to recognise the multifaceted nature of prejudice and its historic contexts. Despite the vigorous political discourse embodied within the exhibition, Edwards’ work is not hostile but rather a call for change. There can be no community without the destruction of systems built to divide us.

Endnotes

[1] Nathanael Edwards, Hear No See No Speak No (self-published, PDF, 2025), 9.

[2] Ibid.

Works Cited

Edwards, Nathanael. Hear No See No Speak No. PDF. Self-published, 2025.

Makayla Dass (Guugu Yimithirr/Kuku Yalanji) is an artist and writer, based on unceded Magandjin land. She is currently undertaking a Bachelor of Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art and works as a Project Officer for Aboriginal Art Co. Makayla is also the Administration Officer for the Aboriginal artist collective proppaNOW. @makayladass