“Blood, bile, intracellular fluid; a small ocean swallowed, a wild wetland in our gut; rivulets forsaken making their way from our insides to out, from watery womb to watery world: we are bodies of water.”—Astrida Neimanis.1

In her most recent exhibition, Sea-Skins 海皮, exhibited at Fortitude Valley’s Outer Space between May and June, Hong Kong-born artist Natalie Quan Yau Tso conflates bodily boundaries with political boundaries and the boundaries between land and sea.

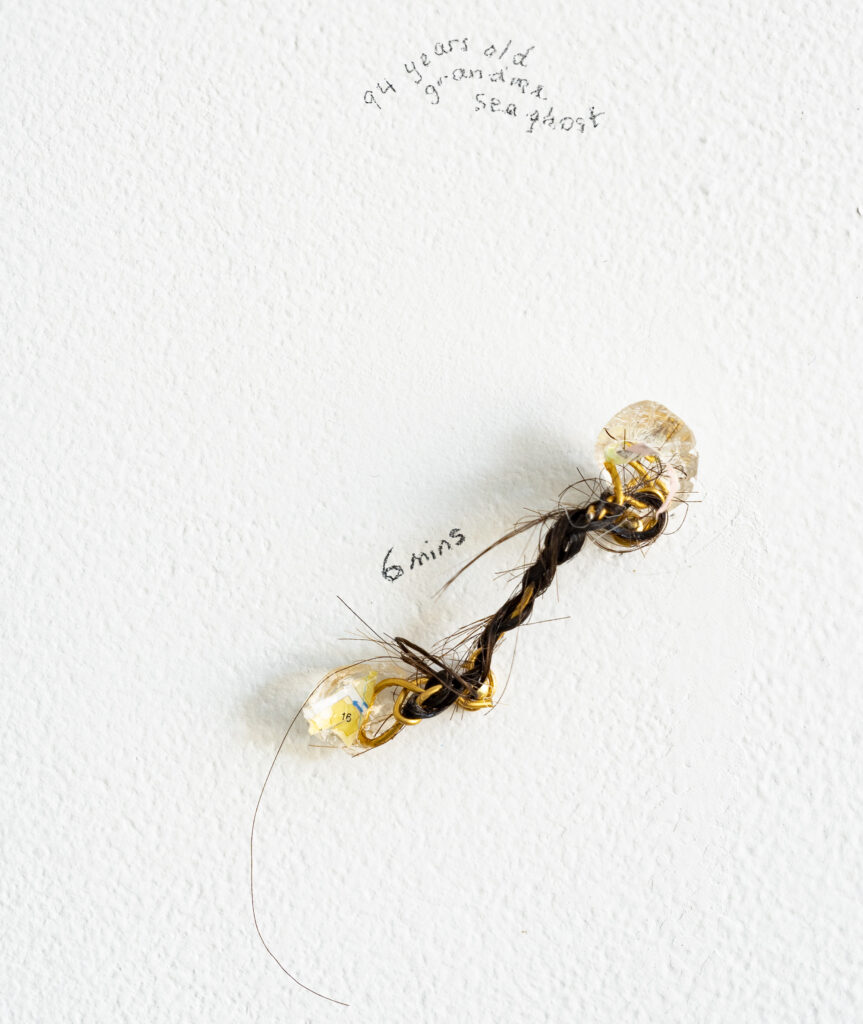

The room is awash with sea-foam green. Paint swirls on the floor like frothy wavelets on the shore, and exposed H-beams painted green stretch to the ceiling of the otherwise cool, white industrial space. In the centre of the room hangs a chandelier of “hardened sea tears 海淚,” its pendants of pearl and ocean-smoothed stones are suspended over a small, clear chalice—“the salt of me and the sea 海水與我的鹽”—that holds an elixir of Hong Kong seawater and the artist’s sweat. The artist has pinned the pages of old street directories to the gallery’s walls, with streets and bodies of water of a Hong Kong past mapped in pink, yellow, orange, and blue; evoking a pastel-tinted nostalgia. Pathways are charted on these maps via strands of the artist’s hair and strings of pearl and jade.

There is a gentle delicacy to Tso’s work, which belies its subtle power as an act of resistance. Through salt water, Tso creates a tidaletic conduit between present and past, using it to recall Hong Kong’s deep histories of rebellion. In the accompanying exhibition text, journalist Louisa Lim recounts Hong Kong’s cultural mythology as a people “brined in defiance,” descending from a fifth-century nobleman who sought shelter in the island’s rocky caves after revolting against China’s Jin dynasty.2 Sea-Skins 海皮 embodies an oceanic choreography of ebb and flow, surging into the lacuna between then and now to connect this history of rebellion to the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests against China’s extradition laws. Responding to Tso’s work, Lim recalls her own memories of these protests as a salty evocation of sweat and tears (2024). She says, “We were packed so tight that we sweated onto one another. There was literally no distance between us.”3

Post-humanist scholar Astrida Neimanis posits in her book, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (2017), that through their watery compositions, exchanges, intakes, and transformations, bodies become permeable membranes connected to other bodies. This porousness resonated as I reflected upon Tso’s work: in salt-soaked protest on steamy Hong Kong streets, these bodies acted as water, swelling and merging together.

But as the uprising dissipated, protesters dispersed across the seas, preferring self-exile to Chinese control. Tso’s work reconciles this diaspora and distance by infusing the salt of her body with Hong Kong sea water. As the artworks in Sea-Skins 海皮 radiate out from this central pillar, through the bodily infusion of Tso’s sweat with Pok Fu Lam seawater, the personal becomes metonymic of the political. Explorations also expand from the interior to exterior, with the artist’s movement through the city being a key component of her enquiry. By mapping her journeys through Hong Kong’s streets with her own hair, on pages torn from vintage street directories, Tso evokes a sense of solastalgia—a melancholia instilled by the loss or desolation of places from which we derive comfort4—at her displacement from home. This echoes a feeling experienced by the wider Hong Kong diaspora, the artists shares, where “returning home is an impossibility when home no longer truly exists.”5 As an antidote to solastalgia, Sea-Skins 海皮 expresses a need to “place, archive, and remember Hong Kong” in order to survive its erasure.

Entering Outer Space for Tso’s opening, I was struck by the minutiae of Tso’s work in the expansive space: whole gallery walls devoted to tiny constellations of maps and small objects placed carefully amidst the floor’s swirls of green paint, including a trail of Tso’s sea turned stones, scattered pages of street directories, and bottles filled with seawater. There is a fragility to these fragments. In turn, stepping into the space could feel like a transgression, yet the small works welcome viewers to look closely, think deeply, and follow the pathways Tso has marked.

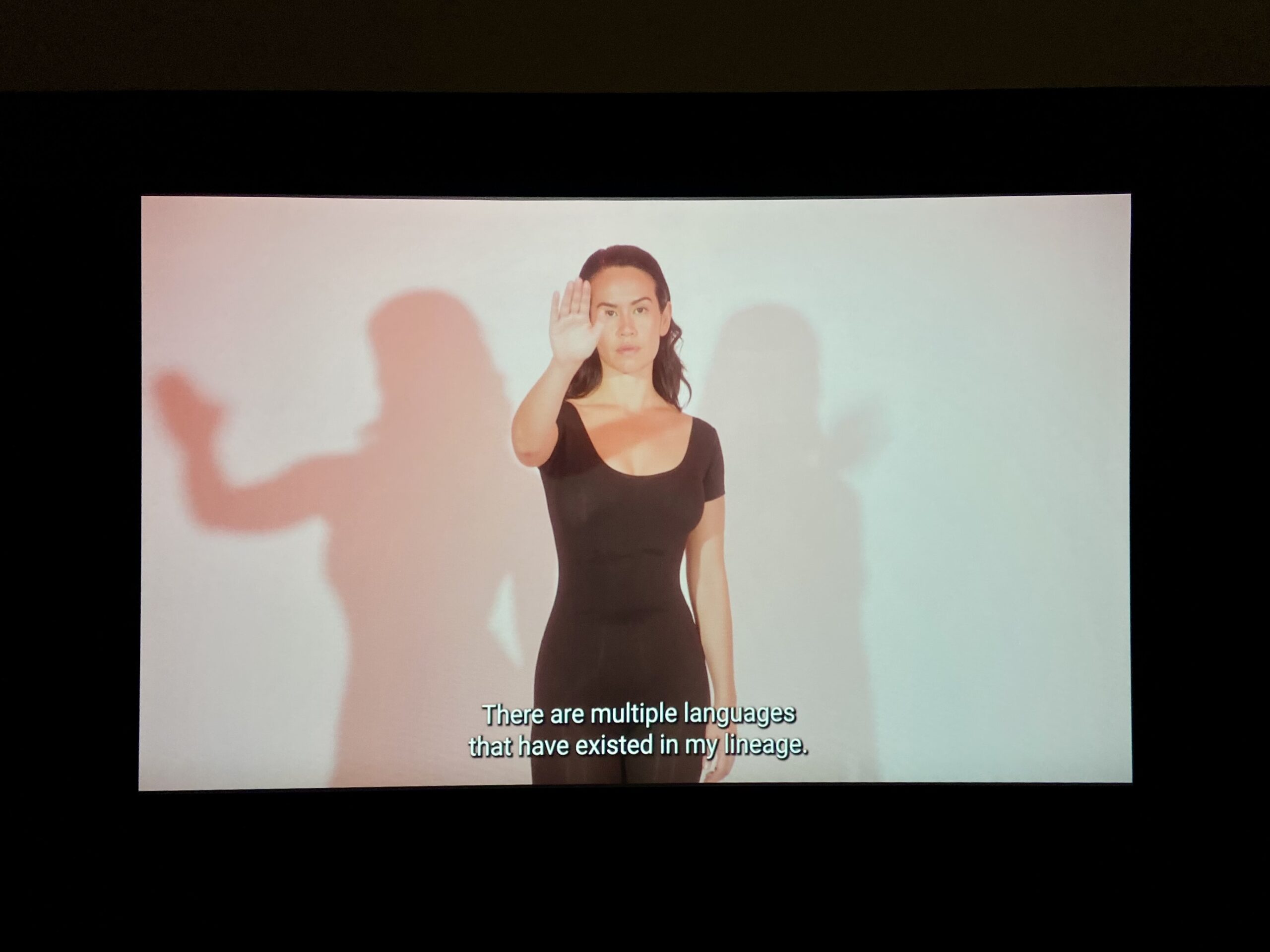

In a conversation with Tso at the opening, she spoke of the role of performance in her practice. Tso noted that this work was a departure of sorts, as she typically centres herself in her works. Instead, in Sea-Skins 海皮, each piece carries instructions to choreograph visitors as they move through the gallery space. For example, the swirling green floor is marked with instructions for making “sea turned rocks 海化石”, guiding the audience to old street directory pages where they are asked to “find the lines where sea meets land” and shred them into a bowl of water, making a pulp that can be squeezed into stones. Directed by Tso’s instructions, the audience becomes an active participant in the work, at once a part of the shifting Hong Kong coastline and the city’s shifting population, while also embodying the artist’s nostalgia as the audience retraces her perambulations within the space.

In Tso’s work, just as pathways converge on maps, so too does the body become a meeting place, a conflation of bodily boundaries with political positions, a site where notions of home and loss are mourned and contested. There is memory contained in salt, and in the movement of a body through space, across time, charted on the pages of a map. And, through water, Tso transcends these borders, as the barriers between artist, artwork, and audience are also broken down.

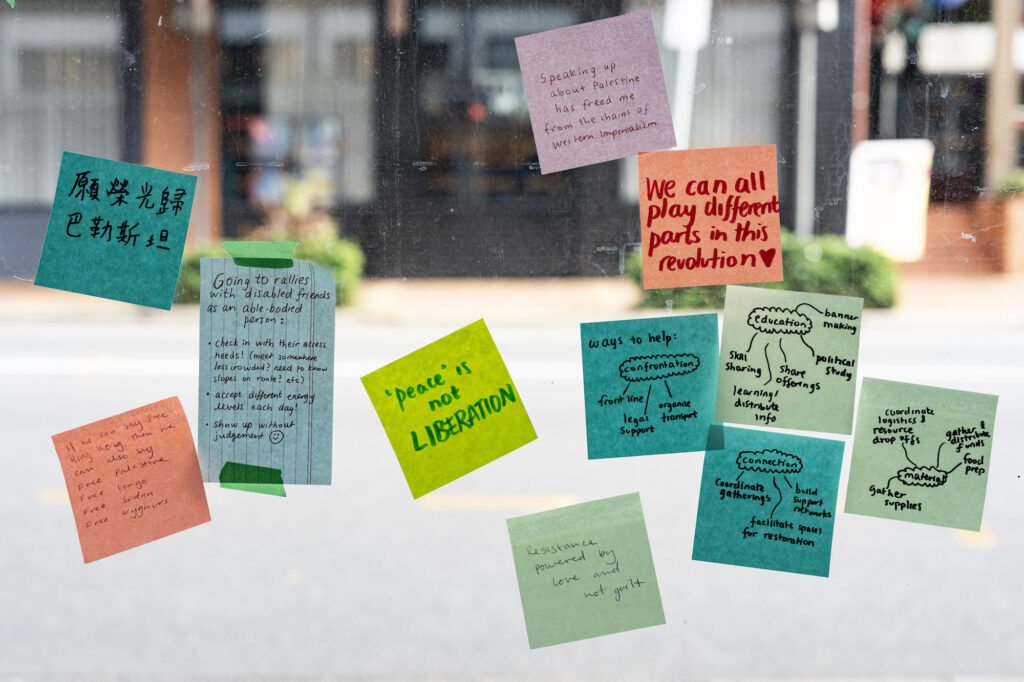

Sea-Skins 海皮 extends a hand across waters to others suffering occupation and colonial erasure—to Palestinians and to Australia’s First Nations people. This solidarity is integral to Tso’s practice, and she asks visitors to engage with it as they enter the space. The gallery window is leafed with hand-written post-it notes, through which Tso asks her audience, “How can we sustain this revolution?” Responses range from messages of hope to personal reflections upon participation in ongoing pro-Palestinian rallies. There is a softness to this form of protest, a reciprocal sharing borne of community-led resistance. It is this quiet power that resonates beyond the gallery walls, and, like the ocean, swells and spreads from shore to shore. When voices join together in acts of collective resistance, Tso raises the provocation that one cannot contain the sea.

- Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), 1. ↩︎

- Louisa Lim, “Sea-Skins 海皮”, Outer Space, May 2024. ↩︎

- Lim, “Sea-Skins.” ↩︎

- Glenn Albrecht, “The Age of Solastalgia,” The Conversation, 7 August 2012. ↩︎

- Natalie Quan Yau Tso, “Sea-Skins 海皮”, May 2024. ↩︎

Felicity Andrews is an emerging arts worker who writes, researches, and creates on Yugerra/Turrbal Land, Meanjin. She holds a Masters of Museum Studies and is currently undertaking a PhD in Art History at the University of Queensland. She works as a cultural mediator at the University of Queensland Art Museum.