There will be a time in life when you expect the world to be always full of new things. And then comes a day when you realise that is not how it will be at all. You see that life will become a thing made of holes. Absences. Losses. Things that were there and are no longer. And you realise, too, that you have to grow around and between the gaps, though you can put your hand out to where things were and feel that tense, shining dullness of the space where the memories are.

—Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk (New York: Grove Press, 2014)

These words are the gateway into Lux Æterna, the latest offering from Ian Friend and Robyn Daw at Teneriffe’s Jan Manton Gallery.

Friend is a Brisbane-based artist renowned for his procurement and mastery of fine materials. Using gouache, ink, and pigments on hand-made art papers, he converses with prominent poets, classical composers, and jazz musicians in a process akin to alchemy. Through a deep respect for his materials, he strikes a balance between control and surrender, ultimately producing work that is delicate and resonant.

Friend’s long-term partner, Robyn Daw, passed away in January 2022. Daw was an artist, curator, educator, program manager, and policy developer. Throughout her illustrious career, she graced institutions including the National Gallery of Australia, QUT Art Museum, and the Queensland Art Gallery (to name a few). In the decade before her death, Daw had been working as the Creative Industries Program Leader at Logan City Council, where she increased cultural engagement within the community.

Lux Æterna (or Eternal Light) marks the couple’s first exhibit together, which, in the wake of Daw’s death, renders it nothing short of transcendental.

I enter the realm of Lux Æterna on the evening of its opening and I am instantly enraptured by The Rose Lake (after Sir Michael Tippet) (2021). The dedication to the English composer is apt considering Tippet’s oratorio, “A Child of Our Times,” is renowned for its themes of shadow and light—themes mirrored by Friend throughout the exhibition. Friend employs the finest of Florentine inks to extend a cochineal salutation. Crimson blazes through warm-white arches paper in ovals that bleed across boundaries and evade containment. In contrast to this unparalleled warmth are shadowy hues of black and blue borne from Payne’s grey; the significance of this homonym is not lost on me as I venture further into Friend’s meditation on grief, absence, and memory.

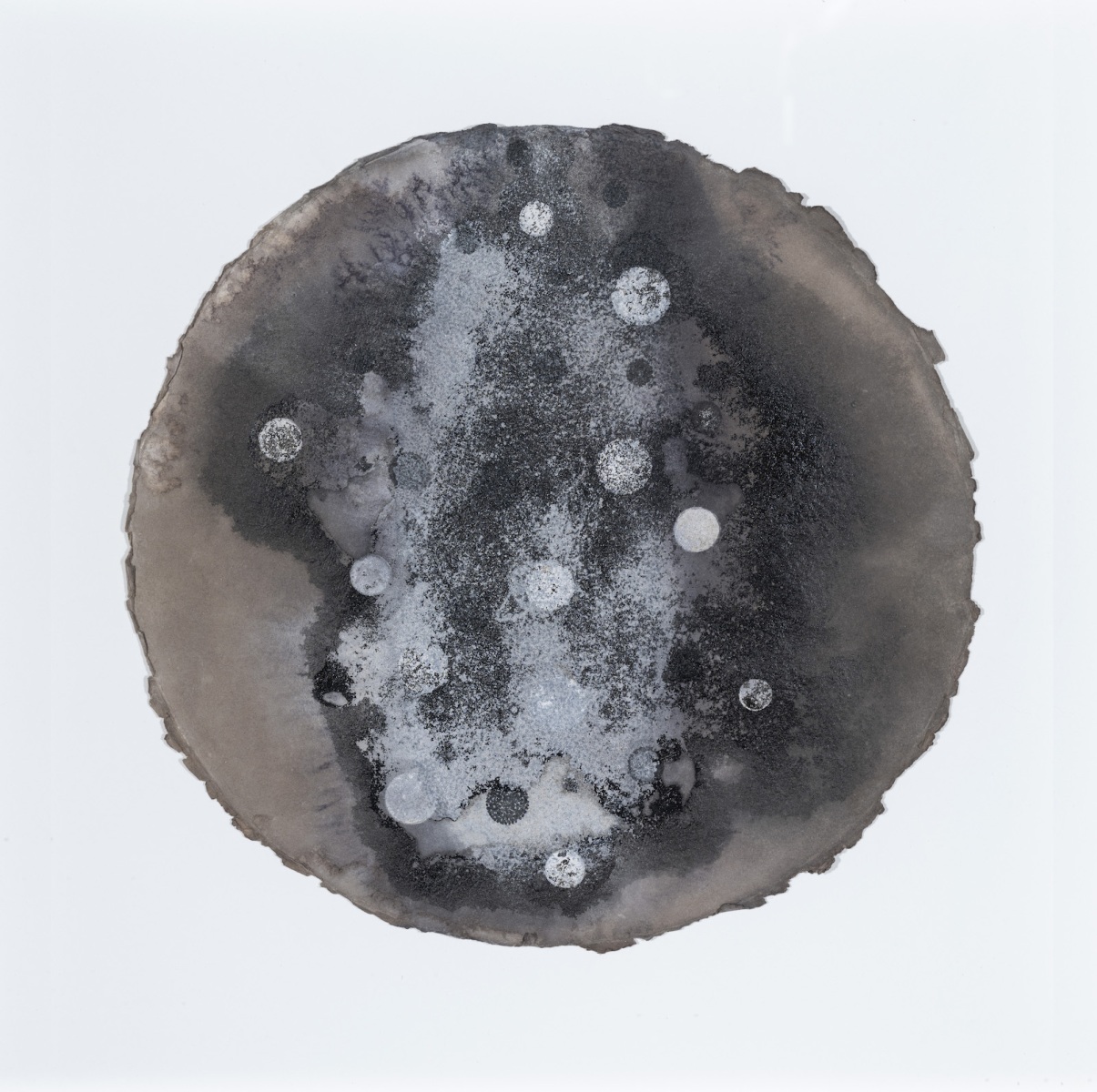

People start to slowly shuffle in; I move deeper into the exhibition. The deeper I get, the darker Friend’s tones become until, eventually, I stand before Black Sun (after Julia Kristeva) (2022). This work responds to Kristeva’s book of the same name, which posits depression as a language that can be learned. This is not an outlandish assertion, given the way that Friend’s Black Sun (after Julia Kristeva) speaks to me from behind its pane of glass. An oceanic orb of Indian ink levitates on a piece of Khadi rag paper, the lightness at its centre slowly succumbing to shadows.

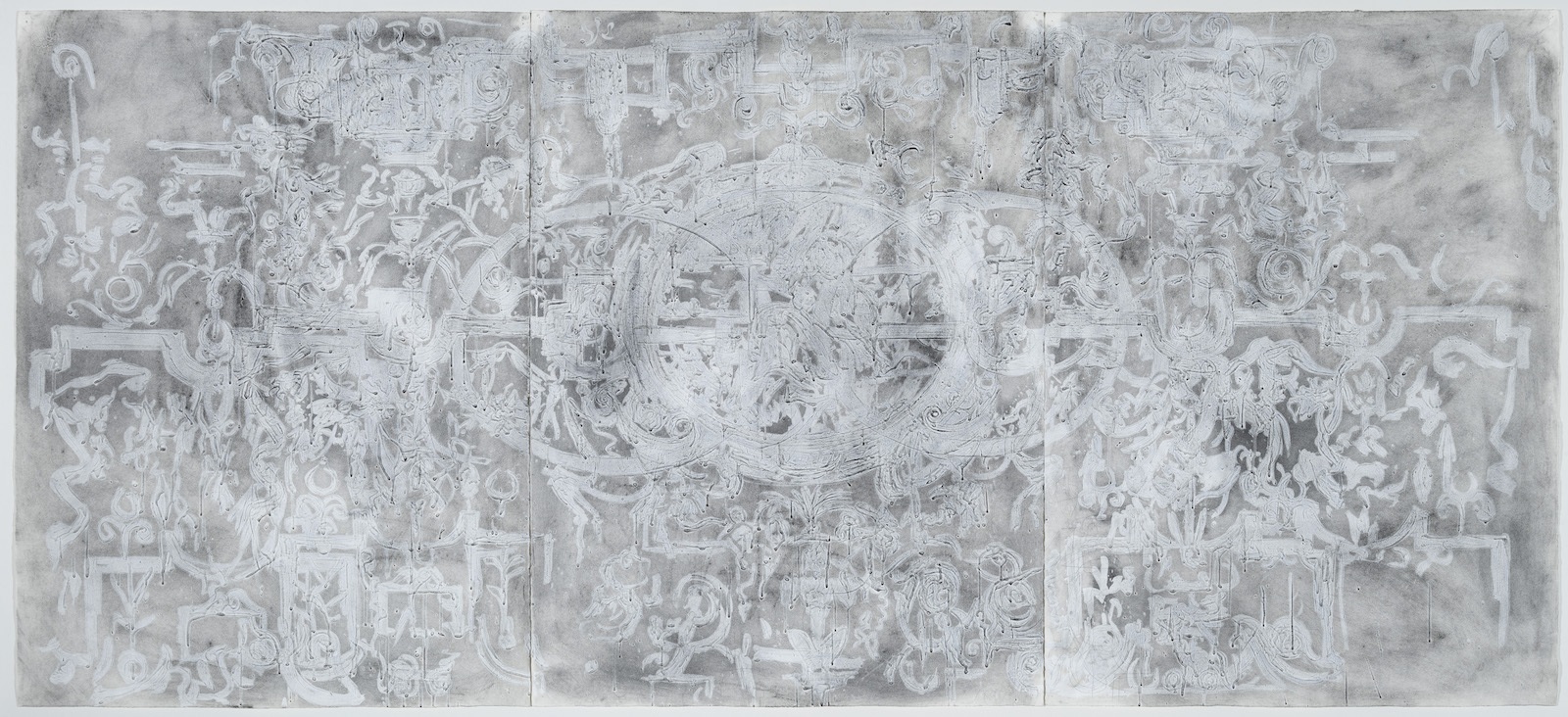

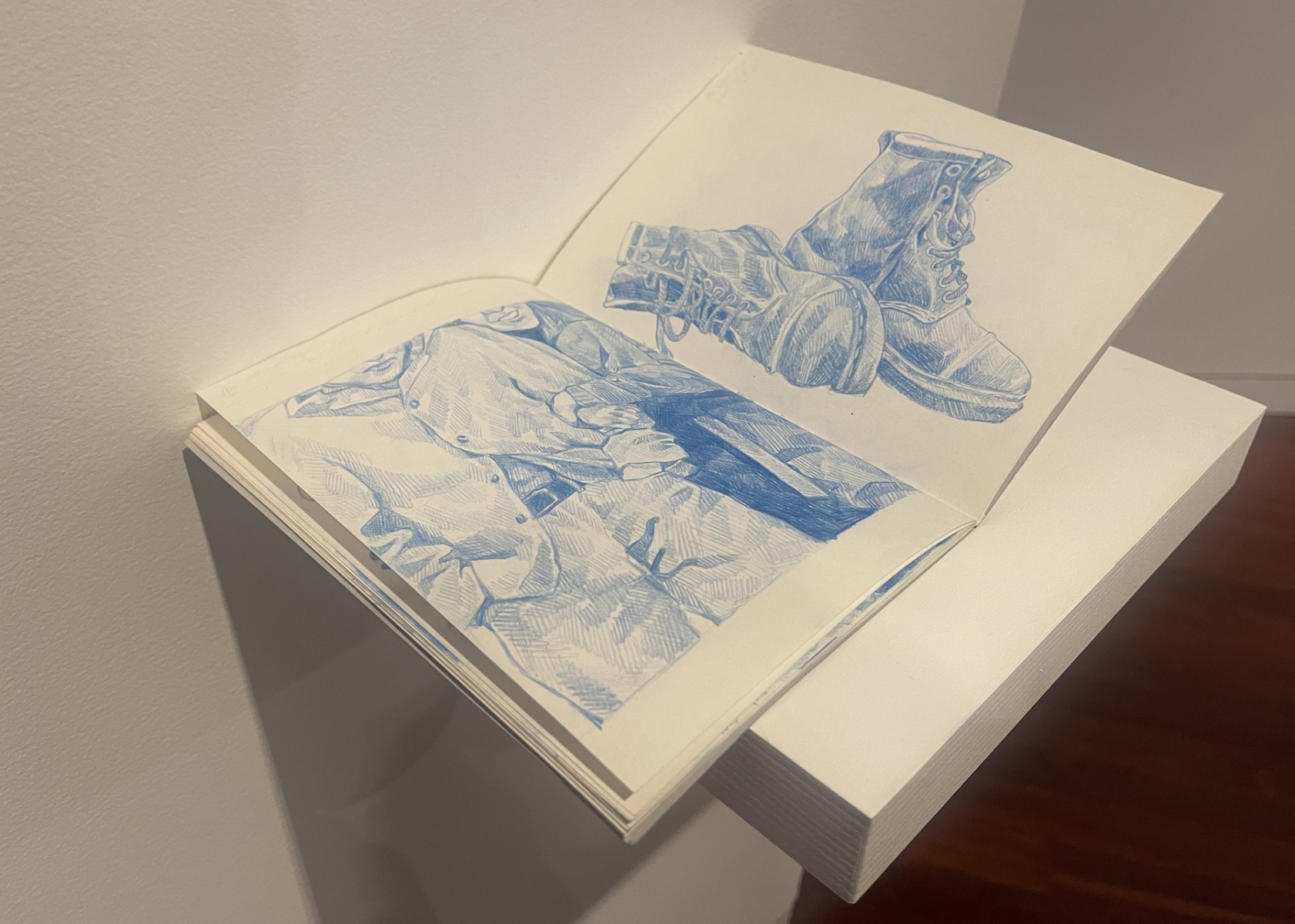

There is no denying that Lux Æterna is an exploration of grief, but it is also a celebration of life—the life of an artist whose attention often wandered to the margins in her search for inspiration. Daw’s exhibited diptych attests to this. Her calligraphic Flore (1994–97) and Cybele (1994–97) were inspired by Antoine-François Callet’s Spring or Zephyr and Flora Crowning Cybele with flowers (1780–81), though not in the way you’d expect. In lieu of responding to Callet’s painting, Daw responds to its ornate, gilded frame. Spanning almost four metres in length, Flore and Cybele emit an energy that presides over the gallery, as if Daw herself is reaching out to you across time and space.

Soon enough, the space heaves with people. Friends and patrons greet one another with an open, easy familiarity, and we gather around the centre of the space for a short discourse from Professor Pat Hoffie OAM. Hoffie speaks fondly of Friend, Daw, and the exhibition. She acknowledges the way that grief ties us together in ways that few other emotions can before sharing a passage from Nick Cave:

Perhaps grief can be seen as a kind of exalted state where the person who is grieving is the closest they will ever be to the fundamental essence of things. Because, in grief, you become deeply acquainted with the idea of human mortality. You go to a very dark place and experience the extremities of your own pain—you are taken to the very limits of suffering. As far as I can see, there is a transformative aspect to this place of suffering. We are essentially altered or remade by it. Now, this process is terrifying, but in time you return to the world with some kind of knowledge that has something to do with our vulnerability as participants in this human drama. Everything seems so fragile and precious and heightened, and the world and the people in it seem so endangered, and yet so beautiful.

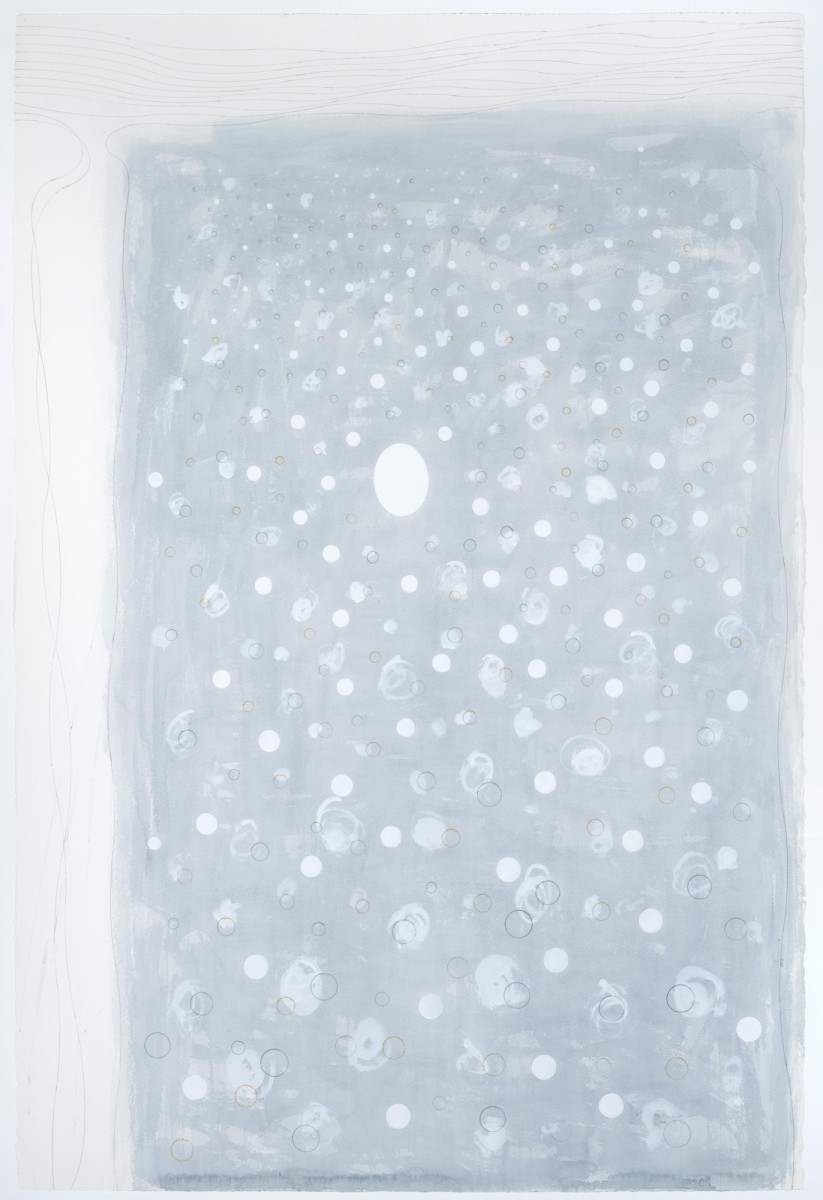

Afterwards, there is applause and a flurry of activity. Friend stands in the centre of the space as people congratulate and converse with him. I catch fragments of their kind words as I stand in awe before his pièce de résistance, Lux Æterna IV (for Robyn Daw) (2022) and Lux Æterna V (for Robyn Daw) (2022). Twin frames contain sheets of arches paper stained with gouache and watercolour. In addition to these materials, Friend incorporates whispers of graphite, which hearken back to the graphite in Daw’s diptych. An opaque, white oval shines inside a panel of pastel blue. For the first time, Friend’s orbs are weightless. Hollow and haloed, they herald a dawn capable of illuminating the darkest night.

In short, Friend evokes the tense, shining dullness of grief and, through his delicate earnestness, unsettles the veil separating this realm from the next. Lux Æterna is a triumph, and a moving testament to a remarkable woman who was oh so clearly beloved.

Darby Jones is a freelance writer and editor with matrilineal ties to the Kamilaroi mob in Southwest Queensland. As an advocate for diverse representation in literature, he has dedicated his career to amplifying the voices of marginalised and underrepresented peoples.