Australia has skeletons in the closet. Metaphorically, of course, but literally too. Multi-disciplinary artist Judy Watson – a First Nations woman with connections to Waanyi Country of northwest Queensland – has spent her career interrogating Australia’s colonial past and present. skeletons is a collection of Watson’s textile and video works curated by Amanda Hayman, with several pieces drawing on evidence unearthed from Queensland State Archives. The works, which entice with a veneer of beauty, urge audiences to open the door to historical atrocities, both personal and national, that have long been suppressed or hidden.

Despite its outwardly serene aesthetic – the works are soft in sound and appearance – it is a confronting and potentially distressing show, as is made clear in a content warning advising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples of violent and racist material. As a migaloo (whitefella), which I am, skeletons leaves no more room for denial.

Opening the exhibition are two sheer red flags – butcher’s apron series flag #1 and #2 (1994) – each with an Australian flag insert in their bottom right corners. The first of these flags displays a quote from a member of Australia’s Save Our Flag group: ‘My main aim is that we retain our monarchy; it is a part of our heritage and we have to leave our country as we received it.’ Watson’s response to this, on a flag hung behind but higher than the first, reads “rape slaughter dispossession”, as if to say the people of these lands know your flag’s heritage; our bodies and spirits remember the price that was paid for your monarchy. Country remembers too. In the video work the witness tree (2018) the viewer is guided through a landscape of steadfast trees on the site of the 1838 Myall Creek massacre, where 28 Aboriginal people were murdered by stockmen. Watson captures 28 trees wrapped in muslin cloth, one for each victim, and as a representation of the superficial treatment of ongoing wounds.

The title of the video work water under the bridge tumamun (2020) spotlights Australia’s desire and insistence that First Nations people ‘get over’ the past. The work, which runs for over 21 minutes and overlays text and historical photographs with an image of a rock plunging through and disturbing a body of water, is a chronological timeline beginning in the early 1800’s of historical facts of the Meanjin/Brisbane region. I didn’t know, until I watched this piece, that there were public executions in this country: In 1855, Dundalli, a Dalambara warrior and resistance fighter, was convicted of murder of two settlers and hanged before a large armed crowd outside what is today Brisbane’s general post office.

I found myself entranced by the large work the names of men (2017). On stained blue and white canvas, and incorporating silhouettes of an old gun and bayonet, 150 names appear over four columns. These names, pulled from written records in the archives, are those of men who ordered or performed killings as a part of over 300 recorded massacres in Australia between 1788 and 1930. As I cast my eye over the piece, I came across my mother’s maiden name, which is, of course, her father’s name. And his fathers. And his. Are we related? I don’t know. Ashamedly, I don’t know much of my own family’s history at all.

skullduggery (2021) is a video work that details the theft of a skull and king plate from the grave of an Aboriginal man, Tiger, known as ‘King of the Mines’ of Lawn Hill near Waanyi Country. The piece combines a map, blood-stained paper, and correspondence between Matron Agnes Kerr from Burketown Hospital and curators at the Welcome Museum in London, who are (almost gleefully) organising the transfer of the skull. This took place in the 1930’s, however, to this day, the Queensland Museum is in possession of the ancestral remains of almost 900 people, stolen from fresh graves and hospitals between the mid-1880s to the late 1960’s. These remains are still waiting to be repatriated.

shadow bone (2022) is a particularly affecting video work overlaying modern-day dental x-rays with archival letters and pencil drawings from an Aboriginal boy from North Queensland, known as Oscar, and from whose 1898 sketchbook is part of the National Museum collection. One of Oscar’s illustrations depicts a group of police (bullymen, as I’ve come to know them here) and stood out to me as a stark and sad reminder of how prevalent the past still is. The soundtrack to the six-minute work is slow and steady crisp footsteps making their way across Country, which I interpreted as the unflinching and enduring journey of First Peoples, even as part of a letter is read aloud – “Four killed by police.”

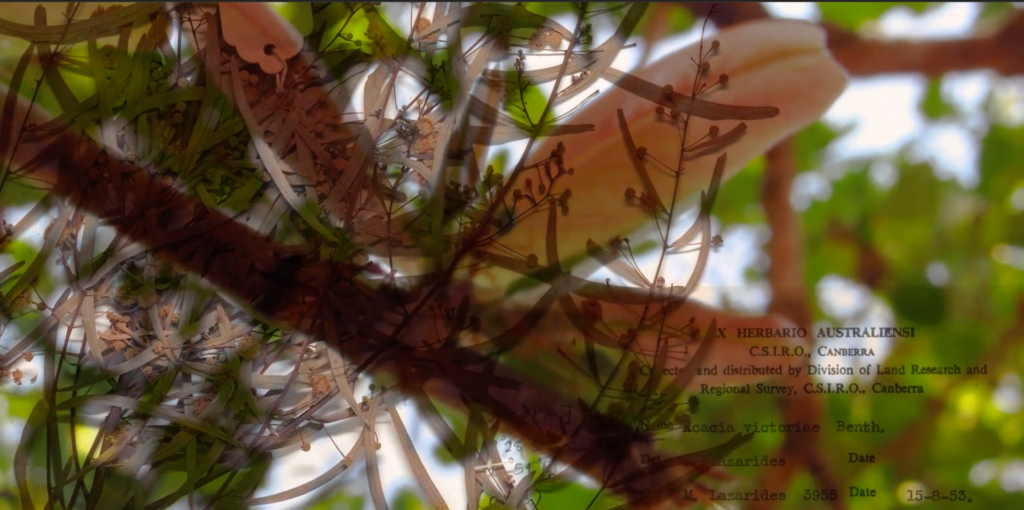

The tone shifts slightly with the most recent work of the exhibition, groundwater (2024). Commissioned by Umbrella Studio and the North Australian Festival of Arts, the 11-minute video was made by Watson and her son Otis Carmichael, and depicts dreamlike images and sounds of Waanyi Country, as well as Litchfield National Park and Mataranka Springs in the Northern Territory. The piece utilises Watson’s signature of overlaying images – here, bodies of water, termite mounds, scientific graphs, maps, botanical illustrations, and photographs of Aboriginal women and children from the artist and her son’s matrilineal line – to tie together the ancient past with a present that still needs protecting.

Watson’s work, and this exhibition, is a declaration: this all happened. There is devastation that still needs to be reckoned with, and perhaps feelings of shame and guilt from non-Indigenous people, Queenslanders in particular, who engage openly with this body of work as a truth-telling exercise.

There is resistance, too, staunch and uplifting. From Ancestors, from Country, from descendants; and from allies joining in ongoing protests, movements and fights. In an artist’s talk with Umbrella Watson said, ‘Artists are activists in the way they are starting to uncover histories, and through their artwork they share [what they have learned] with the community.’ She also said she believes her role as an artist is one of education and that her aim is ‘information, inspiration, and activation.’ Leaving the exhibition – which is brutal but presented with a level of grace that astounds – I find myself filled with all three.

Jessica Martin is a human, writer, and youth worker based in Gurambilbarra/Townsville.