A matrilineal turn, kinship and panic at the museum.

I confess this is less a review of Judy Watson’s extraordinary mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri at QAGOMA and rather a rumination on a turn in socio-political agency of the museum, kinship, and the personal panic of the author.

In late December I had the good fortune to visit the new wing of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Modern. The whole experience was quite spiritual. I really enjoyed the architecture of the new building, particularly going in and out of the main exhibitions and being bathed in natural light, reacquainted with the landscape present through the large walled windows. The Louise Bourgeois retrospective was particularly transcendental, moving from ‘the day’ on the ground floor to ‘the night’ in the tank, the eternal inquiry of the artist’s work, across more than 60 years, kept rising, posing questions on the meaning of the human experience. It didn’t provide the answers, however it was very moving.

I felt like I had ‘filled my cup’ — until, as I was rising to the first floor on the escalator, I had a sudden panic. What if we in the arts are all caught up doing busy work, while ‘the world burns’ (both literally and metaphorically). Attempting to soothe myself, I thought “no, it is important work, it speaks to power, it advocates and creates change, it touches hearts and minds.” Yet change is slow and crises are so urgent. This simmering panic sat with me until I had the privilege of attending the opening events of mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri (tomorrow the tree grows stronger), a retrospective of Waanyi artist, Judy Watson.

I was struck by the celebration of one artist’s contribution, not in isolation — the normalised form of ‘artistic genius’, a myth usually white, male, and hetero — but in kinship and collaboration. The frame of this exhibition is radical for an institution, each contribution and act of sharing goes to a resistance of the violence of mono-narratives, often of colonial shape. It acknowledges all the voices, our shared accountability, and the power of ‘together-ness.’ Through her collaboration with community members, Watson’s work challenged the traditional power structures of the art world, particularly those dominated by privileged men.

At the opening, Kooma and Nguri nation poet and land rights advocate Cheryl Leavy’s powerful opening address captivated the 600-odd attendees and embodied this togetherness. It did leave following speaker, Mark Bailey MP, charged with the usual acknowledgements, with no hope of maintaining the buoyant crowd’s attention. The exhibition, sharing forty years of Watson’s practice, is curated with QAGOMA Kullilli/Yuggera curator Katina Davidson. The opening coincided with the anniversary of their meeting, ten years ago, when Davidson was a participant in the South Stradbroke Island Indigenous Art Camp and Watson was a mentor.

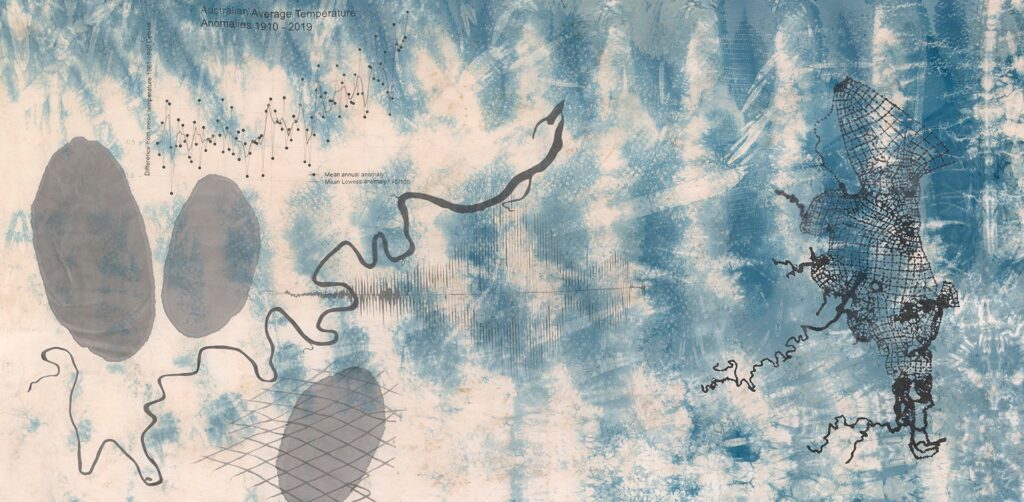

The works are organised into four themes, including identity: running water people; the archive: rattling bones at the museum; feminism: a bleeding of consciousness; and environmental: water as weapon. Entering QAG, in the central foyer space you are greeted with salt in the wound (2008/2009), an installation that shares the story of Watson’s great-great grandmother’s escape, hiding in the windbreak, from a massacre of the Waanyi peoples on Lawn Hill Station by the Native Police. It is just one of the works that shares the horrific truths of our share narratives, passed down through matrilineal oral history.

In the Watermall you find walama (2000), originally created for the Sydney International Airport, a collaboration with Kuninjku artist, Belinj Susan Marawarr. In thoughtful exhibition design, the light reflected off the water dances on the cast forms, which represent termite mounds and upturned dilly bags. Marawarr is a master weaver, bark painter, and sculptor often overshadowed by her brother, ‘the rarrk master,’ Balang John Mawurndjul AM. Exemplifying the feminist thread of Watson’s career, collaborations with her female First Nations counterparts are evident in every decade represented.

Other collaborations include our skeletons in your closets (2015) with Delvene Cockatoo-Collins of the Nunukul, Ngugi and Goenpul peoples and video explorations of the making of tow row (2016) with Quandamooka artist, Elisa Jane (Leecee) Carmichael. At the opening, Watson proudly wore a new creation by Wakka Wakka, Butchulla and Gurang Gurang artist and curator, Shannon Brett.

Watson had lost her voice by the time Saturday’s artist talk came around, however this enabled another embodiment of the artist’s sense of togetherness, with friends and colleagues speaking to her work as she whispered adages to their reflections in their ears. Gallerist Josh Milani spoke of Watson’s practice of friends and family being invited to the studio to dance on the fabric of her mixed media paintings, creating the movement of swashes of paint of the ground in her work.

40 pairs of blackfellows’s ears, lawn hill station (2018) presents 40 pairs of wax cast ears fixed to the wall with rusted nails, created with the assistance of Kokatha and Nukunu artist Yhonnie Scarce. This work, made a decade after salt in the wound, refers to a startling vision of brutal trophies, a warning, that has been shared through oral history, later to be ‘verified’ in the dairy of a young white colonial woman, Emily Caroline Creaghe.

Having not seen this work before, upon my return to Gurambilbarra (Townsville, North Queensland), I have been sharing the experience of it with those in our community asking about Watson’s exhibition, struck by its conveyance of the genocidal horror of the frontier wars of our region. Reconciling histories that we are all complicit in is challenging. Many pastoralist and agricultural family narratives are adapted through a need to defend one’s existence as born into this dark history, these are a kind of kneejerk apologia that are designed to ease a sense of guilt, however guilt is often not the point of works like Watson’s so much as an acknowledgement of past misdeeds. Last year’s referendum result, wherein Australians were asked to vote on a constitution change enabling an Indigenous voice to parliament, and the ‘YES’ campaign was defeated, seems to have emboldened a crushing of truth-telling. The latter has been marginalised as part of a shift toward labelling anything critically engaged as ‘woke.’ Returning to the panic of my own personal ‘busy’ work, it is in Watson’s work I find salve. Through her work we find a pathway to have conversations about the hard topics.

That a living, working, female First Nations artist collaborated and had their own agency in the narrative of their contribution to the world in an institution like this is historic. The themes woven throughout the exhibition, from feminism to environmentalism, serve as a poignant reminder of the urgent need for intersectional activism. Watson’s art embodies resistance and resilience. But perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of Watson’s exhibition was its emphasis on togetherness as a practice.

The answer to my panic at the museum came in the form of this radical shift and ‘inreach’1 rather than outreach that sees an intersectional, matrilineal swing in Australian institutional practice. A small part of the panic still remains, however as a friend recently pointed out: perhaps that panic serves a purpose, to stay focused, work with intention, embody the change we wish to see, and be united together through cultural practices.

- Emelie Chhangur, Director-Curator of Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario, discusses ‘inreach’ as a decolonising curatorial model in an interview with Jennifer Fisher, “Institutional Inreach as a Feminist Curatorial Methodology,” On Curating, Issue 52, November 2024. ↩︎

Kate O'Hara is the Director of Umbrella Studio Contemporary Arts. Umbrella is a leading independent platform for contemporary and experimental arts practice operating on Wulgurukaba and Bindal Country (Townsville, North Queensland).