Barrambin (Victoria Park) emerges as a green sanctuary amidst the bustle of the surrounding city. Road noise dissolves into song from the birds that inhabit its surrounding waterways, and the cityscape all but disappears behind the tree tops of the lush rolling parkland. It is otherwise quiet on this brisk Sunday morning as I cross the threshold between city and nature to view a recent series of site-responsive public art installations titled EverGround.

In an accompanying essay, “A Catalogue of Site,” Dornell Wylie speaks to the project’s engagement with the complex and layered histories of Barrambin. The parkland bears deep cultural and spiritual significance to the Turrbal people who inhabited its formerly lush wetlands and open woodlands, using it as a hunting ground, camp site, and meeting place for the many First Nations peoples travelling through the area. However, as the colony of Brisbane expanded, Barrambin was deforested to make space for industrial activities. This resulted in the polluting of waterways and dispossessing Turrbal people of their lands. EverGround continues a dialogue with this history of place, responsive to its cultural and ecological significance, and indebted to the Knowledges and traditions that have been passed down by First Nations Elders.

The exhibition comprised a series of temporary sculptural artworks, produced by multidisciplinary undergraduate students of QUT’s School of Creative Practice. Works were installed for a week and activated in an afternoon of programming including dance, participatory movement workshops, grounding meditation, and community crochet beneath the canopy of Evie Mathies and Charlie Petrenko’s Connectivity Enclosure (2024).

Mathies and Petrenko’s work is the first that I encounter as I ascend a hill from the carpark, grass spongy and damp beneath my feet with the morning dew. A woven, triangular sail extends between the branches of a small copse of trees, establishing a space of shady respite that is both enclosed and open to the surrounding parkland. The sunlight filters through its patchwork canopy, stitched together with squares of hessian and crocheted jute twine and sisal rope. Suspended from the trees and this canopy, crocheted spirals dangle to swirl in the breeze. With Connectivity Enclosure, the artists pay homage to Barrambin’s history as a gathering place for First Nations communities, inviting visitors to pause beneath it and consider their connection to one another and the environment around them. This work provided a contemplative entrance point for the exhibition, a sheltering space that afforded a moment of slow looking and stillness as I admired the craftsmanship of its interconnected panels. Connectivity Enclosure, like other works in the exhibition, displays an attentiveness to its material presence within Barrambin’s ecology. The exhibition is attuned to environmental consciousness, emphasising materials that can be repurposed, regenerated, or returned to the earth.

EverGround’s artistic intervention within the landscape unfolds as a series of incidental encounters that I find charming. The next artwork I spy is nestled amidst the sprawling roots of a nearby tree. Beneath the Soil (2024), by Sianan Lyall, is a series of unfired terracotta spheres that have been carved with patterns to make them appear as though woven. The sculptures seem to emerge from the soil itself, molded to the shapes of the tree roots as though they had grown to fit the spaces between. Nature added its own little sprinkle of magic to this artwork. Sprouting between the sculptures and surrounding tree roots, a cluster of mushrooms bobbed their caps, dewy from the overnight rain. Beneath the Soil is imbued with ephemerality: over time, the raw terracotta will eventually erode and rejoin the earth. But the small green tufts of dichondra repens—a native drought-tolerant plant—that spring from the opening of each vessel, locate this decay in a larger cycle of regeneration, beneath and above the soil.

At the crest of the hill, Jemima Carey’s The Motions (2024) rises like a sharp, angular ridge, casting a long shadow over the lawn. This work is a functional sundial constructed from reclaimed timber panels. As the day passes, its shadow shifts between the ring of black ovals that surround it to mark the passing of time. The vertical plane of the sundial swirls in a silhouette of the bends of the nearby Maiwar. Evoking the river, The Motions draws parallels between Barrambin and its ecological history as a flood plain. Through the waxing and waning of shadows throughout the day, the work speaks to both the brevity of small moments and also the continuity of larger planetary cycles of change and renewal, which exist beyond human perception. There is a note of hope in this work that, even in the wake of our sustained impacts, nature will persist.

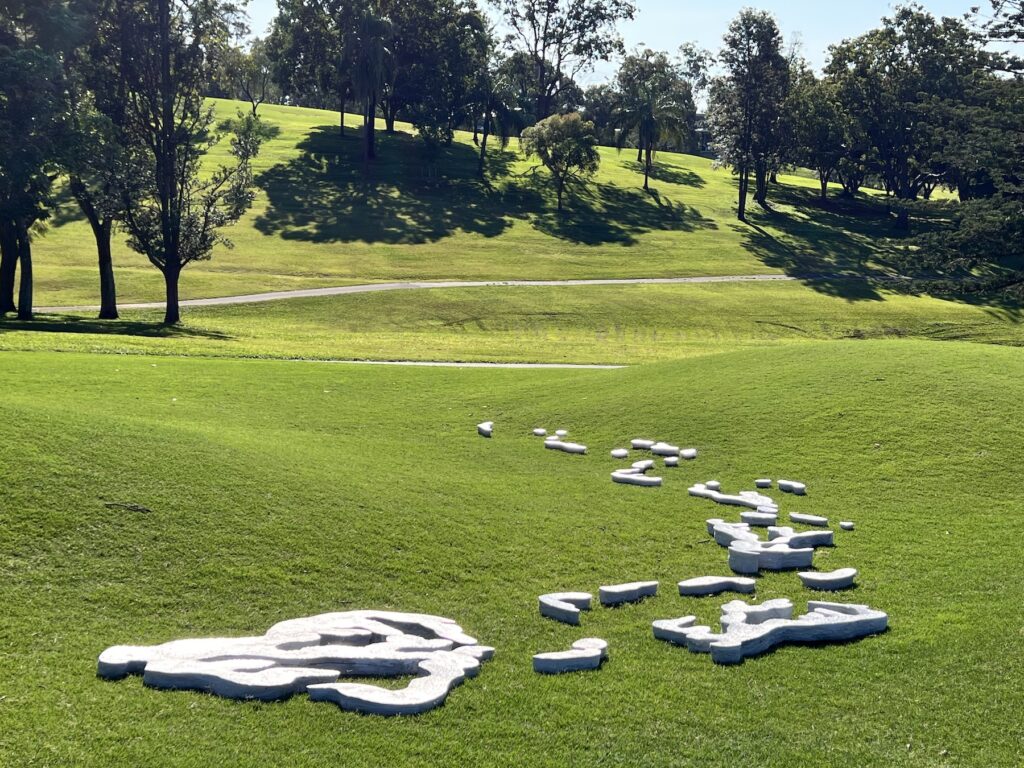

The Motions creates a moving dialogue with neighbouring artwork, Flow as a Function of Time (2024) by Liana Barret and Ruby McCarthy. In both works, time and waters coalesce, ebb and flow, to mark the ways in which the flood-lanes and waterways of the site have retreated and been reshaped with the ongoing development and repurposing of the site. In Flow as a Function of Time, a glinting aluminium river courses between the undulating green swells of the parkland, mapping the contours of Barrambin’s original waterways and catching the sunlight to create the illusion of movement, like ripples.

Barrambin is a site in flux, and EverGround establishes a space to contemplate its entangled cultural and ecological histories. Conceived as a “walking narrative,” its installations create a pathway that guide visitors through a story of place, community, cultural memory, and time. The temporariness of its situated artworks carries a poetic resonance that speaks to the cycles of its changing history. That poetry rings bittersweet with the knowledge that this precious inner-city green space is once again a contested site. In the lead up to the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games, the parkland is scheduled for development into a new stadium complex. Asserting the parkland as a space to gather, create, play, and connect to one another and the environment, EverGround speaks to the vital need to defend our city’s public green spaces. In viewing its artworks, I can’t help but reflect upon the rich heritage of the site and how much we stand to lose through its irrevocable destruction. In this light, the works take on a contemplative and memorial quality, speaking to the loss of what was and what could be, advocating for the land’s preservation.

Felicity Andrews is an emerging arts worker who writes, researches, and creates on Yugerra/Turrbal Land, Meanjin. She holds a Masters of Museum Studies and is currently undertaking a PhD in Art History at the University of Queensland. She works as a cultural mediator at the University of Queensland Art Museum.