There is something of a sense of child-like regression about being invited to play with your food; of giving in to previously forbidden impulses. So rarely, too, do we receive invitations to wonder, mystery, and whimsy. Entering the dark, digestive maw of Elizabeth Willing’s Kitchen Studio, showing at Metro Arts as part of Brisbane Festival, is such an invitation. As our party assembled at the threshold of the studio—an intimate gathering of nine, many of us strangers to each other—we were instructed by our guides to turn off our phones, that we could leave at any time, but upon doing so, could not return. I felt a sense of entering a locked-room mystery as we ventured into an unknown and puzzling space.

One of the most delightful things about encountering Willing’s work was how little I knew going into the experience. A precursory search on the Metro Arts website revealed only an enigmatic list of ingredients ranging perplexingly from the organic (coffee beans, passionflower tea, vanilla bean, rosehips) to those that sounded more at home in a chemistry lab (Butylated hydroxytoluene E321, Magnesium silicate E553, Potassium aluminium silicate E555 & E171). As we were ushered through the doors, I found myself questioning what shape this culinary journey may take. (For readers adverse to spoilers, who would like to enter Kitchen Studio taste-unseen as I did, this is the point where we tumble down the rabbit hole into Wonderland, so proceed with caution).

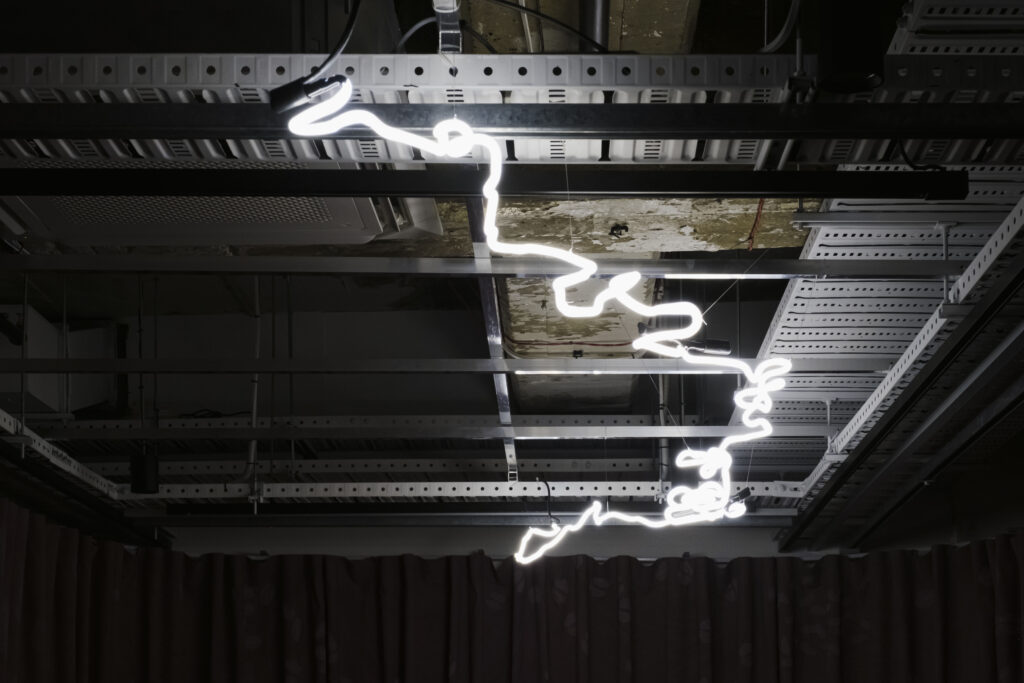

We made our way through a winding, intestinal, pink-curtained corridor emerging into a dim, industrial room lit only by a twisting neon light above. The digestive nature of this journey was enhanced by a binaural soundscape, at once organic and industrial: a swirling, amniotic swell between the walls that built in intensity. We settled into the communal bench in the centre of the room, made from twisting metal pipes, also pink, that put me in mind of food extrusion machines. An uncertain energy oscillated amongst my fellow diners as we speculated what was to come. Then, slowly, two performers in olive jumpsuits crossed the space in front of us, and without a word, drew back the curtains to reveal a video screen that was to serve as our guide through this curious degustation.

Kitchen Studio blends sculpture, installation, and gastronomy in an immersive, multisensory performance, where food serves as both the material and subject of her interdisciplinary practice. Each course prompts a dialogue about the ecology of food, and our relationship to what, and how, we consume.

To begin, we were proffered a hefty volume listing herbal infusions that corresponded to each of the 300-odd E-additives currently found in Australian food. After an intensive consultation with my neighbour, I selected E507, Hydrochloric Acid – a delectably spiced blend of rooibos, ginger, black pepper and chilli.

In a later course, one of our hosts served a tray of dusted chocolate nuggets presented to us one at a time, on bended knee and with an enigmatic smile upon her face, while her colleague instructed us to let the chocolate sit on our tongues until it dissolved, not to bite, as there was a chance that one of them may contain a kernel of real gold at its centre. Behind him, the video screen displayed a desert scape, juxtaposing floating golden ingots with melted gold skulls and rifles, the apposition of the sweetness on my tongue against the implicit violence inviting reflection upon the bitter costs of the foods we take for granted. The chocolate dissolved to a hard centre, and as I pressed it between my teeth, it cracked and filled my tastebuds with the earthy, bitter taste of coffee. Alas, no gold.

In perhaps my favourite course, we were presented with a sealed, beeswax vessel, and as the screen displayed an abundant, technicolour flower garden, we were invited to pierce the vessel with a straw and siphon the sweet nectar from within, akin to a bee collecting honey.

Willing has previously discussed her research-based approach to art as coming from three styles of “kitchen”: the mother, the chef, and the machine.[1] Where the mother dominates the home kitchen, cooking as a labour of love and centring the kitchen around the family and dining table, the chef produces food in an extraneous space, supplanting the emotional relationship to the diner with entertainment and creativity. The third kitchen, that of the machine, offers a contemporary and horrifying lens, considering the uncanniness of highly processed food and “as a consumer makes [us] question our hospitality towards this indigestible matter.” [2]

Kitchen Studio’s curious hospitality is highly effective in its capacity to defamiliarise the familiar act of dining in a conflation of these three spaces. The hosts’ performance embodies a mysticism that seemed to satirise the ritual and rules of a fine dining experience. And, as diners, we are centred in this theatre, complicit participants in the cycle of food from growth, to harvest, to processing, to service, to digestion. However, while the strangeness of the space may dislocate the audience at first, challenging the way we encounter food, we find a touchstone within this strangeness. At its core, Willing’s Kitchen invites its participants to come together at the table in the familiar custom of sharing a meal and curious conversations.

______

[1] & [2] Elizabeth Willing and Carody Culver. “Gut Instinct: The Art of Consumption,” Griffith REVIEW, no. 78 (2022): 146–52.

Felicity Andrews is an emerging arts worker who writes, researches, and creates on Yugerra/Turrbal Land, Meanjin. She holds a Masters of Museum Studies and is currently undertaking a PhD in Art History at the University of Queensland. She works as a cultural mediator at the University of Queensland Art Museum.