Editors note: The artist and the Sam family kindly request that you do not take photographs while in the exhibition. This exhibition contains sacred cultural information that is not intended to be viewed or shared outside of the gallery space. The images shared in this review have been pre-approved by State Library of Queensland.

Content advice: This exhibition includes stories and information that may be disturbing. Sections of the exhibition include offensive and derogatory terms which are unacceptable today. The exhibition contains words and descriptions that may be culturally sensitive and which might not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Visitors should be aware that this exhibition contains images of, references to, and names of deceased persons, including of Aboriginal ancestors.

Queensland has a bloody history that we still reckon with today. Massacres, forced removals, stolen children. The state’s Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (known amongst mob as ‘The Act’) embedded protectionist and segregationist policies within government and emboldened social and systemic racism that is still perpetuated today. This racist history of Queensland has cemented us in the nation’s consciousness as conservative and backwards, an image reinforced by the election of a conservative state government that immediately shutdown the state’s Truth-telling and Healing Inquiry and repealed the Path to Treaty Act in 2024. However, art prevails as both a form of social commentary and an act of resistance.

The unbroken spirit of the Kalkadoons is a dialogue between Country and the Kalkadoon (Kalkadunga) People through the artworks and stories of Colleen Sam, her mother Aunty Ena Sam, and their Ancestors. When you first walk into the gallery, you hear the trickling of water, splats of rain. Toward the back of the space, claps of thunder signal an impending disaster – colonialism carried in on storm clouds. To the left of the entrance is a narrow corridor; upon its left wall is the Sam family tree. Information about Sam’s Ancestors form an image of dislocation and incarceration, and words like ‘captured’ and ‘killed’ highlight Frontier violence at the hands of settler-invaders.

At the end of the corridor is the first of many video interviews with Sam and Aunty Ena. With the sound of rumbling thunder in the background, the mother-daughter duo talk about the importance of water and not allowing Country to die. When Aunty Ena talks about Country she gets a teary, far-off look in her eyes as if she is mentally reaching back to the land she talks about. To the right of this video is the entrance into the main gallery space, a large, well-lit room with art and additional videos spanning three walls. This is a shock in comparison to the dark, narrow entryway; it’s as if the corridor temporarily shields the viewer from the truth-telling to come. However, if we are ever to achieve reconciliation in this country, we must leave the dark and step into the light, unveiling the harsh but real impacts of colonialism and invasion on Aboriginal peoples.

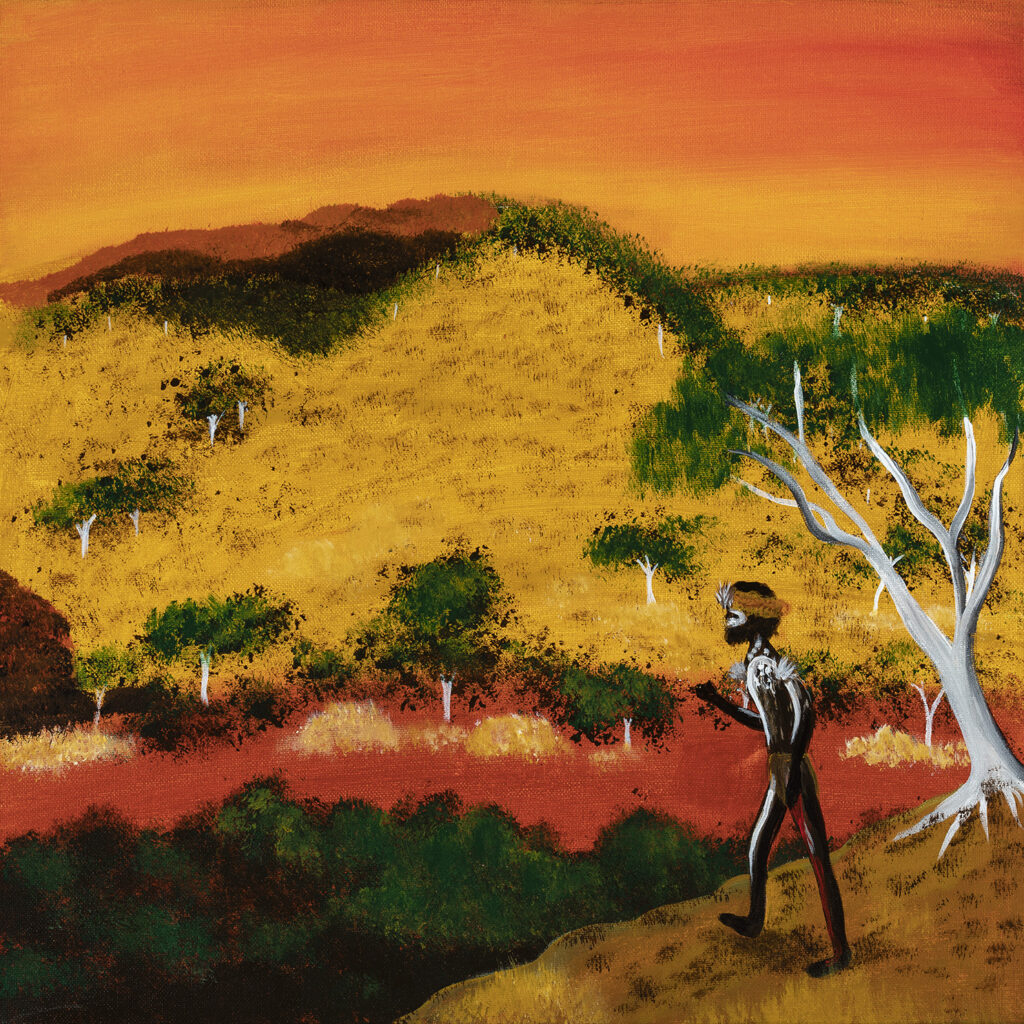

In her dual role as visual artist and knowledge holder, Sam has created rich artworks that showcase the stories of massacres and violence against the Kalkadunga People and why it’s so important that we, as Aboriginal peoples, tell our own truths. The left wall of the larger gallery space holds paintings that track Sam’s family’s resistance across generations. Traditional (Kalkadunga) life (2021) is juxtaposed against First contact with the white man (2021), showing the same visage in two startlingly different ways. The former shows Country before colonisation, harmonious with strong kin ties and collegiality between human and animal and earth. The latter sees this peace set ablaze as it depicts displacement, massacre, ruin. Similarly, Polly takes refuge in Waanyii Country (2024) sees Sam’s Ancestor fleeing a station with a full, lush waterway in the background. This rests next to The conflict of natural resources (2021), which depicts a depleted river and a dead bullock in the foreground. This shows the introduction of invading species and the extraction of natural resources that have been cared for by the Kalkadunga People since time immemorial.

Country is key to the dialogue of this exhibition. Water Dreaming is emphasised in multiple ways: through the soundscape woven into the gallery space, the depictions of Water Country in Sam’s artwork, and the way water is acknowledged in the video interviews. A 360-degree animation inhabits the middle of the space, showcasing Water Country and the black cockatoo (Sam’s totem), whose squawks resonate throughout the space. Scattered throughout the exhibition are references to Battle Mountain, a site of trauma and resistance for the Kalkadunga People. It is there that a battle known as “The big finish up” occurred; its lingering presence is a reminder that Country and her People are an archive of memory.

Aboriginal knowledge has always been passed down orally, a tradition that was stifled by colonisation but never fully suppressed. This intergenerational lens is projected in the video on the back wall of the gallery, Sam is joined by Aunty Ena and another Kalkadunga Elder, Aunty Judy Sam, who helps tell the stories of their Ancestors and how these stories are passed down the generations. Sam acknowledges growing up off-Country in Brisbane, and admits that these stories act as invisible strings, always leading her back home. Striking depictions of how one story told by the mother is passed down through her child are shown through sketches along the back wall that were drawn by Aunty Ena and reimagined in paintings by Sam (such as Aunty Ena’s Compound (c. 1991) and Sam’s The Compound (2021)). An historical timeline that moves from the back wall to the right wall allows the viewer to physically travel through these intergenerational connections.

Moving along the right wall, the viewer glides into Kalkadunga Dreaming, where lore and cultural stories are generously displayed. This aspect of the exhibition transcends Western understandings of place, particularly in the depiction of Land and Sky Countries within Brolga and Emu Dreaming (2024). Here, the depiction of Dreaming or ‘Lore stories’ evoke spiritual connections to Country, animals, and people as well as the role stars and space play in the continuation of our cultures. There are elements of secret/sacred lore in these Dreaming stories that are inaccessible to the lay person but, to the Kalkadunga People, grant access to a wealth of knowledge. Knowledge that our colonisers attempted but failed to eradicate. Sam demonstrates the imperative for Aboriginal peoples to tell our stories our way, emphasising that we are the only people who can.

The exhibition closes in an alcove adjacent to the Dreaming paintings, where the viewer is encouraged to take respite. This Learning and Healing Space contains mats and chairs, allowing the viewer to stop, breathe, and sit with what they experienced. Motifs from the Dreaming stories are depicted in this space and a video interview plays in which Sam and Aunty Ena talk about perseverance through trauma, the power in healing, and strengthening one’s spirit through passing on knowledge, stories, and identity. Here, the viewer is asked to acknowledge intergenerational trauma and grieve the past, while also understanding that Aboriginal peoples never lost our culture: we’re still here and here we will remain. As always, the conversation circles back to the land, with Sam likening Country to a vital organ – a living thing that, when damaged, wreaks a broader havoc.

When moving through this exhibition, Country was ever present, but she also felt just out of grasp. It reminded me of my own experience of living and working off-Country. While my memories and stories travel with me, there’s nothing more healing than visiting home. The State Library of Queensland (SLQ) resides on the banks of the Maiwar (Brisbane River) overlooking the skyscrapers and industrial cranes of the Brisbane CBD. The unbroken spirit of the Kalkadoons does a great job at pulling us out of our city-centric lives. It is a moment of pause, of respite. However, it does raise the question: will this exhibition go on tour? With links to approximately 26 Indigenous Knowledge Centres across the state, SLQ could showcase truth-telling and healing across rural and remote Queensland. This is especially important when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are often expected to travel to capital cities for personal and family history research and information. Given how vital Country is to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and our way of life, it would be incredible to witness this exhibition sit in-dialogue with Country, on Country.

Though government decision-making has stifled any formal proceedings, truth-telling and healing always have been and always will be innate within Aboriginal cultures and expressions. Our stories are stifled, yet we continue to rise up, louder than ever. The unbroken spirit of the Kalkadoons is an invitation for all Australians to learn more about the true history of this country through the lens of the Sam family and the Kalkadunga People. It also asks us to investigate our own histories and acknowledges that we all have stories to tell.

Raelee Lancaster is a Meanjin/Brisbane-based librarian and writer. Her writing has featured in The Guardian, SBS Voices, Meanjin, The Big Issue, and Australian Poetry Journal. Raised on Awabakal land, she is descended from the Wiradjuri and Biripi peoples.