QUT Art Museum’s current exhibition, As Above, So Below, is part of the program for the 29th International Symposium on Electronic Art. ISEA, an international non-profit organisation, encourages interdisciplinary discourse and exposure for culturally diverse organisations and individuals working with art, science, and technology. It produces a symposium each year in a different city and country—with associated exhibitions, performances, and events. In 2024, it was held in Brisbane.

As Above, So Below—a term that can be interpreted to mean that events in the spiritual world are echoed in the physical world—brings together recent works by Australian and international artists who engage with our environment by investigating ecosystems, endangered species, air quality, eco-acoustics, and plant-human relationships.

On walking into QUT Art Museum, I headed to the left-hand-side galleries, first seeing German artist Tamiko Thiel’s mixed-media and virtual reality installation, Elemental Spaces (2023). As luck would have it, the interactive component of this work wasn’t active on the Sunday I visited—although the other interactive exhibits worked well—so I moved on to Honolulu-based, Native Hawaiian artist, Tiare Ribeaux’s projected video, Ulu Kupu (2022).

Ribeaux’s films employ magical-realism to reimagine present realities and future trajectories of lineage, healing, and belonging. The Ulu Kupu video shows a fascinating dance performance representing the harvesting of particular plants and material from the land, including: hala, which is used for weaving; wauke, used to create tapa (a textile); and hau, used as a decorative fibre.

Nearby, Art for Nons (artists Lea Luka Sikau, Denisa Půbalová, and Antje Jacobs from Germany, the Netherlands, and Australia respectively), have devised BUG (2023), an encounter between a human spectator and a bug. If you peer into an instrument resembling a telescope (a retro-looking 3D printed version), you first see a video of an underground world which then transitions into a video feed of your own eye. We are told that “BUG comments on humanity’s drive to control nature, and reverses the position of the spectator into a surveilled subject.” I struggled to understand how the work actually did this.

Next to BUG is Tully Arnot’s (Australia) virtual reality installation, Epiphytes (2022). Here you can wear a headset that gives you a 3D representation of Arnot’s childhood backyard featuring diffuse and shifting images interspersed with audio interviews as well as field recordings of local birds and sounds. It’s an interesting experience.

Around the corner is Daniel Miller’s (USA) Mutual Light (2023), a bright and lively display of interactive flower forms—made from recycled milk bottles—where heat from the viewer’s body is detected by each flower, causing the forms to change colours at different intervals. A simple enough concept, but effective.

In the far left gallery is Xenoangel’s interactive, three-channel video, Soft Waters (2024), produced by Samuel Twidale and Marija Avramovic from France. It’s an experimental video game where the viewer, using a game controller, can play the role of director. Soft Waters—a story of time and a water goddess from 30,000 years ago—is worth playing with.

Had I initially headed for the right-hand-side galleries at QUTAM, I would have first come across the work of Ross Manning and Anna Tweeddale, artists well-known in this part of the world. Their engaging work, Personal Turbulence (2024) from the project A Cycle of Air: Site 1, raises questions about how we might ethically live and breathe on our shared planet amid unstable atmospheric and bio-political conditions.

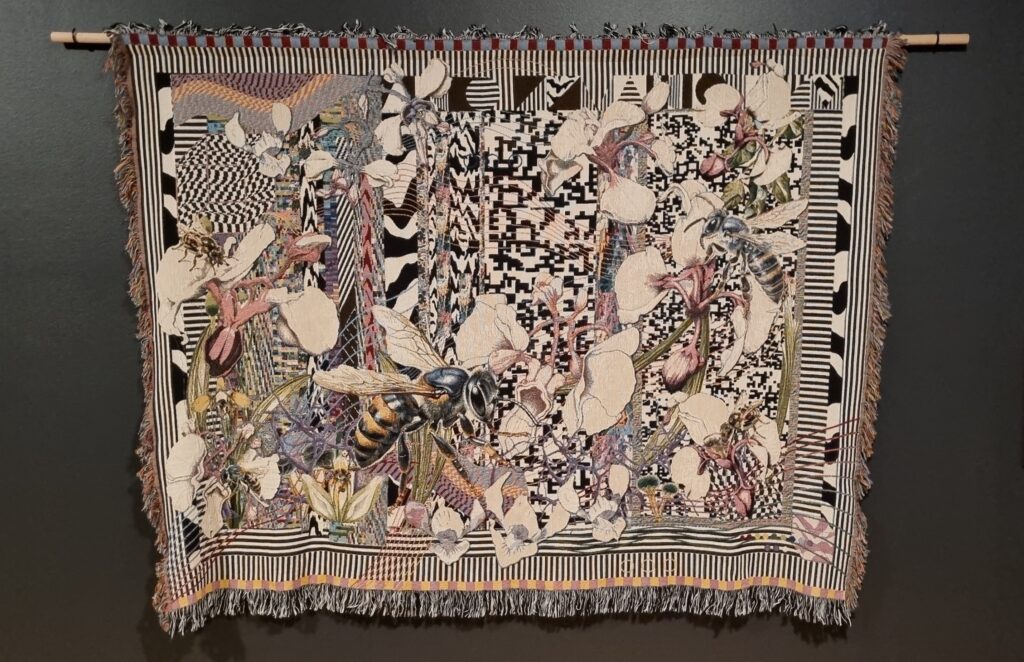

In the adjoining space is artist Kate Geck’s Impossible Evolutions (2023), three charming tapestries that have used generative machine learning models in the design of the weave. The project imagines iterations of endangered Australian butterflies and wildflowers, including the Sunshine Diuris orchid.

In total, there are 15 exhibitors. Others in the exhibition are: Robert Andrew, Michele Barker+Anna Munster, Oliver Hull, Anna May Kirk, Anna Madeleine Raupach, and Nicole Smede, all from Australia, and Scenoscosme (Grégory Lasserre and Anaïs met den Ancxt) from France.

The first ISEA was held in 1988 (in Utrecht) and Australians have long been involved, with two previous symposia being held in Sydney in 1992 and 2013. Apart from this one in Brisbane, I’ve only attended ISEA in Sydney in 1992, and in Istanbul in 2011 (in part because it coincided with the Istanbul Biennial). I remember 2011 as a particularly entertaining and complex event across multiple venues, with substantial Australian involvement including Priscilla Bracks’ and Gavin Sade’s electronic crickets, the group Terra Virtualis, Nigel Helyer, Paul Brown, John Tonkin and Mari Velonaki, Troy Innocent with Indae Hwang, among others.

The ISEA 2024 program, titled Everywhen and co-directed by Gavin Sade and Wesley Enoch at QUT, took place over 10 days in June, with several exhibitions continuing well after the symposium. All up, Everywhen’s program gave us around 200 works by over 100 artists, from Australia and other countries, showing in many different kinds of venues around Brisbane and south-east Queensland.

There were several events at Griffith University’s Queensland College of Art and Design, including exhibitions, projection installations, and performances developed through GU’s Creative Arts Research Institute (CARI), on one of ISEA’s opening nights. Channelling Dulcie’s Piano (with Vanessa Tomlinson, Jesse Budel, Greg Harm), Endless (Andrew Brown), Co_Sonic 1884km2 (Robertina Sebjanic), and Bones (Peter Thiedeke, John Ferguson, Chris Stover), were all part of the latter.

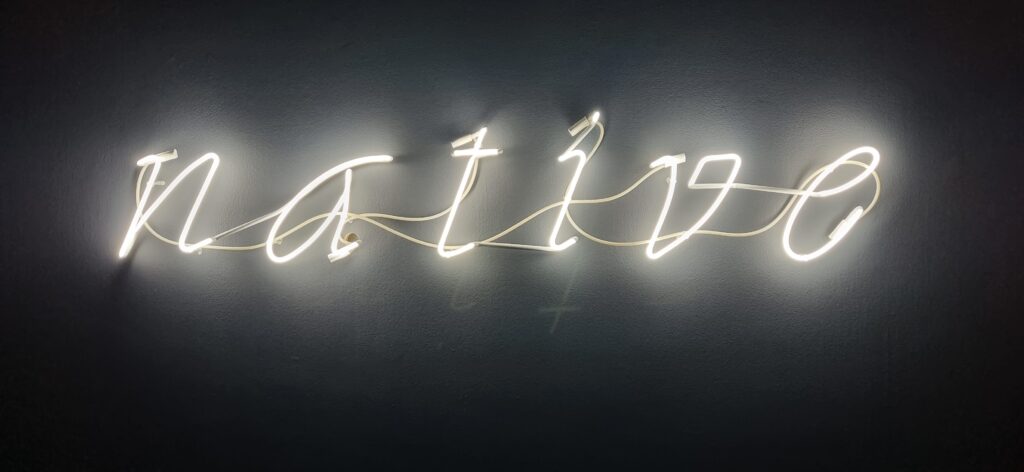

Opening the same night, and also part of ISEA, was Griffith University Art Museum’s exhibition, r e a: NATIVE. An artist, curator, activist, researcher, and educator; and descendant of the Gamilaraay, Wailwan, and Biripi peoples; r e a investigates Indigenous identity, representation, and the post-colonial experience using photography, digital media, film, video, and installation. In this exhibition, two interrelated installations explore historical, colonial, and personal archives. In the first room there’s a remastered iteration of r e a’s Native (2013/24), a site-responsive sound and neon installation developed as part of an Indigenous Artist Residency at Blacktown Arts Centre in 2013. In the second gallery is Native (yugal/song), 2024. Moving through the darkened spaces; seeing the dramatic, abstracted video images; and hearing the soundtracks; all the senses are engaged. Here video and motion sensors encourage viewers to use their bodies to experience sound in a visual form. In short, these installations are compelling.

Over decades, ISEA has aimed to be a “significant forum for exchanging ideas and presenting cutting-edge work in electronic art, science, and related fields.” These ideals are not easily reached and some works in these current ISEA exhibitions struggle to get there. It can’t be enough to say an artist has accomplished a high level of technical achievement: at its best, art also needs to be adventurous and evocative. We like an emotional takeaway.

Ian Were writes on contemporary art, design, and culture and has recently written short stories. Since 1997 he has edited more than 20 art books and publications, including 12 books as a freelance editor.