The Courthouse Gallery would close in an hour yet I wasn’t going to miss All Come Under: Darren Blackman, Zane Saunders + Bonemap.

Walking through the doors to the gallery, my body remembered the colonial rituals associated with a courtroom: keep your eyes straight, bow at the magistrate, don’t look around.

Next, my body was directed by a breeze. I encountered a massive shear of fabric, green, grey, and white panels stitched together vertically, falling from the ceiling and moving across the courtroom floor: Darren Blackman’s work. The veil was weighted and felt somehow earthly, dropping straight to the floor from a metal pole that was attached horizontally to the ornate colonial ceiling and then secured with metal grommets, like those that would secure a flag. I love materiality and read everything in the room this way. I am not disappointed.

The remaining fabric spread across the timber floor beams, dancing in the wind from fans hidden behind. The fabric is filled with light-yellow, golden printed symbols⎯symbols that spoke to me culturally: a boom box, a metal grate, a television, an Aboriginal flag. A further series of designs that resemble a circuit board dropped vertically. When they hit the ground, they morph into organic, gestural markings that evoke plant fibres, pandanus imprinted by Blackman’s hands and his plant companion, radiating gesture and movement, dancing through the space making me aware of my own body and its connections to the space.

Blackman’s work creates an experience in direct contrast to my expectations of a courtroom. It sings up Gimuy country, surrounding and overpowering the ornate, white-lit mouldings and symbols of the 1900s courthouse. The latter is given space only to become a material symbol in Blackman’s work.

I am mesmerised, compelled to become part of the work. I sit in front of the waving, pandanus-struck fabric for a long while. I listen to the sounds of everyday life moving around me, coming from four visible speakers in the corners of the courtroom. There are times that the rhythms of the sounds overlap and everything changes; the fabric becomes still.

The audio is layered with familiar noises of everyday labour—cleaning, dump trucks, cleaning, birds, buses, more cleaning, and Gimuy bird songs. The call of noisy miners, likened to colonisation’s invasive force, echoes amongst the bustle. They, unlike powerful crows, remind me of the disruption of native ecosystems. Sounds of people working remind me of the lives subject to Australia’s colonial law system; they serve as commentary on the disconnection colonial capitalist society fosters between people and with the environment. There is so much presence and absence in this work. It reveals the forces of Country, always present but often ignored.

I stand up. I don’t want to turn away from the dancing fabric; nevertheless I move to face an absent judge.

The main courtroom contains silky oak fittings, including a marking on the wall where the Judge’s bench once was, as well as a lion and unicorn crest lit up in a decorative arch on the wall behind. French doors and casement windows are separated by plaster pilasters with detailed cornices.

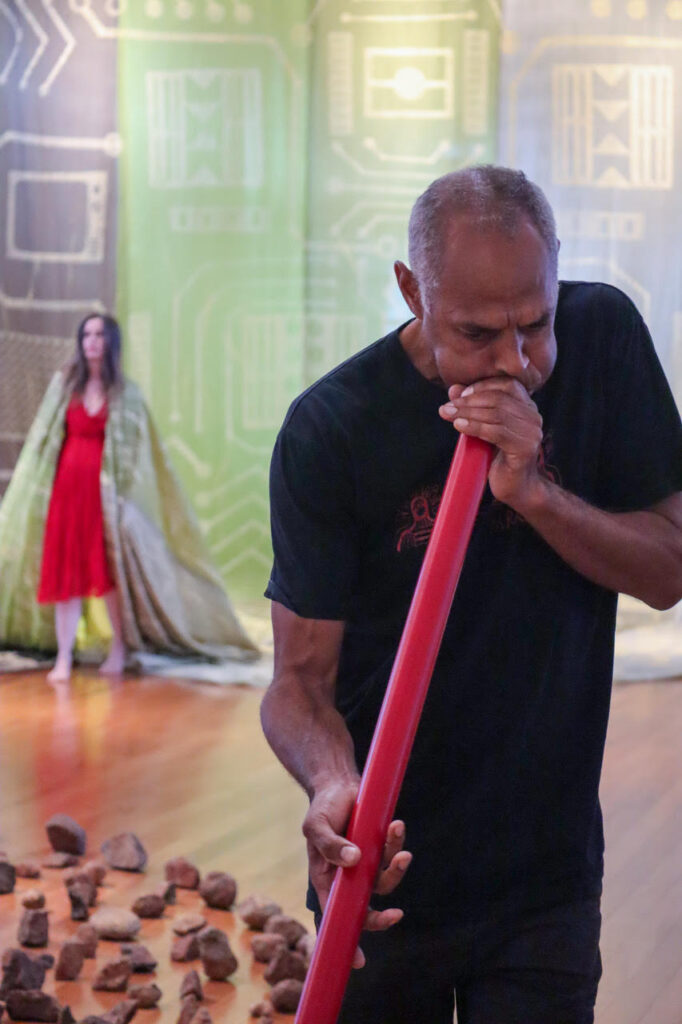

Facing this way, I am drawn to Zane Saunders work: an assemblage of rocks that form a circle on the timber floor. A square made present by absence sits inside the rock circle, offering a cultural statement on the subordinate position of the colonial legal system within the broader framework of Aboriginal law, to which we all inherently belong and ‘all come under.’ Each rock is hand placed, each stone belongs to somewhere and works here to make present the strength of Country and its people. That grounding feeling returns in my body, like when I walk the creeks on Kabi Kabi Country where I live. Every stone reminds me that I have all the tools I need to survive. I can not help but feel Saunders has used these rocks before and they are joining him for a while on his journey as an artist and an activist in colonial space and time.

A red PVC yidaki (didgeridoo) leans on the back wall where the absent judges bench holds space. It points up toward the English crest on the wall. I became aware of a giant red aluminium hoop which I’m surprised I hadn’t noticed directly when I entered the courtroom. This circle hangs vertically over the horizontal circle and absent square of rocks on the floor. It reiterates the circle of law that encases the lion and unicorn of the United Kingdom’s coat of arms, making the latter small and insignificant despite its spotlight. The hoop makes me imagine a circus event is about to be performed.

The hour I had before the gallery closed extended as Darren Blackman joined me in the courtroom and the gallery staff let us stay on. Bonemap’s installation of the works in the courtroom gallery delivered a sense of movement and embodied presence that lingered well beyond their opening performance with the artists—an event I unfortunately missed but heard many speak of afterward.1 I could have spent hours in this exhibition. It really spoke to me. Ritual, performance, absence/presence, and relationality are tools that are close to me.

As time passed, light in the gallery changed, reminding me that Country is always present. The exhibition’s mood also changed with the movement of light and the breath of the fans. Like Country, it embodied me; it was dynamic, unpredictable, and imbued with agency and activism. All Come Under insists on active engagement, urging audiences to become a witness in the courtroom to colonial systems and the ongoing law of Gimuy Country; urging us to listen, feel, remember, and become part of the work. In its totality, All Come Under provides a deeply reflective and activist exploration of cultural survival, the persistent impacts of colonisation, and the enduring voice of Sovereign Indigenous Country.

All Come Under: Darren Blackman, Zane Saunders + Bonemap was a Cairns Indigenous Art Fair satellite exhibition.

Libby Harward is a contemporary conceptual Quandamooka Aboriginal artist from Australia whose work draws on the cultural narratives of her Ngugi ancestors to challenge colonial narratives and assert Indigenous sovereignty. As the founder of Munimba-ja Art Centre, Harward is also a dedicated advocate for the continuation of Indigenous knowledge through community and professional development initiatives.