As I stepped inside PARKER Contemporary, I noticed the ceiling had disappeared. Or rather, the walls didn’t reach it. They rose just high enough to suggest enclosure, then gave way to concrete and metal piping. Above me was an industrial void, and all around me were wall-hung eyes—algorithmic retinas, polymeric pupils—that constricted and dilated with glassy ambivalence. They weren’t, of course, literal eyes or even images of eyes but a visual arrangement of artworks by Alethea Richter with enough symmetry and gloss to give the impression of eyes.

It says more about the viewer than the work, perhaps, that I kept thinking of Richter’s works in Pulse Systems via a kind of speculative figuration. It is an interpretation that the works seem both to accommodate and elude, and though my analysis would move in other directions, that early response continued to inform my perspective. What was required was a spectatorship that is attentive, participatory, and attuned to the shifting codes of visual culture. This is the terrain in which Alethea Richter’s practice is rendered.

Pulse Systems situates itself in conversation with the post-digital world. This world is not one where we have moved beyond digital technologies, as the term “post” might suggest, but rather, one where we are all so deeply intertwined with tech that its novelty and visibility has faded. The digital is no longer new, separate, or “Other” to or from us. It is ambient, banal, and omnipresent. In the post-digital world, we are all born or naturalised residents of the digital.

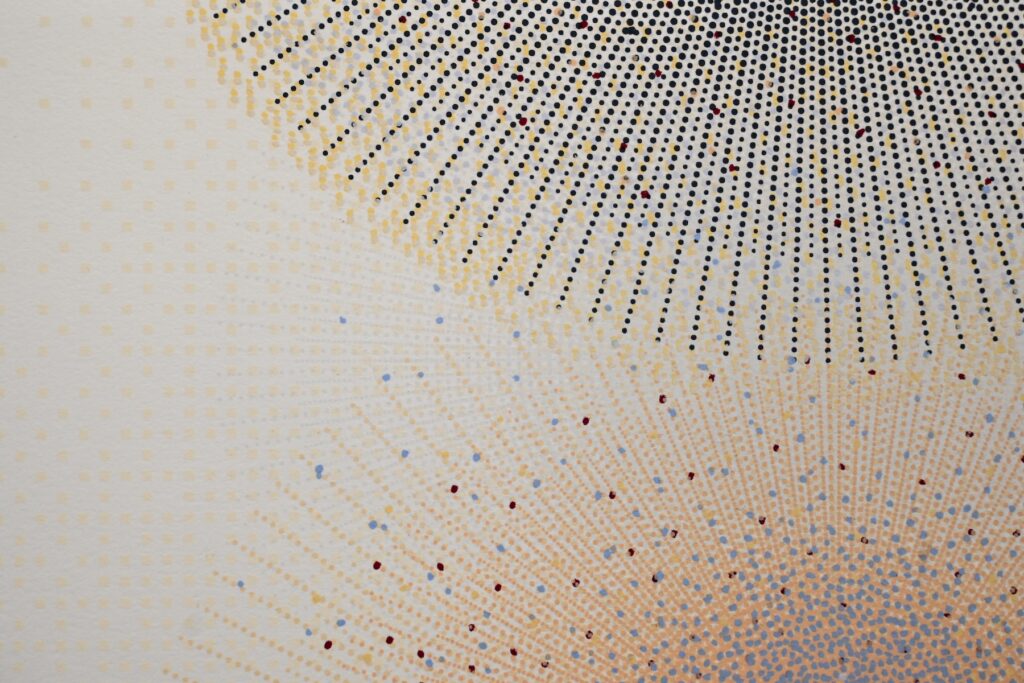

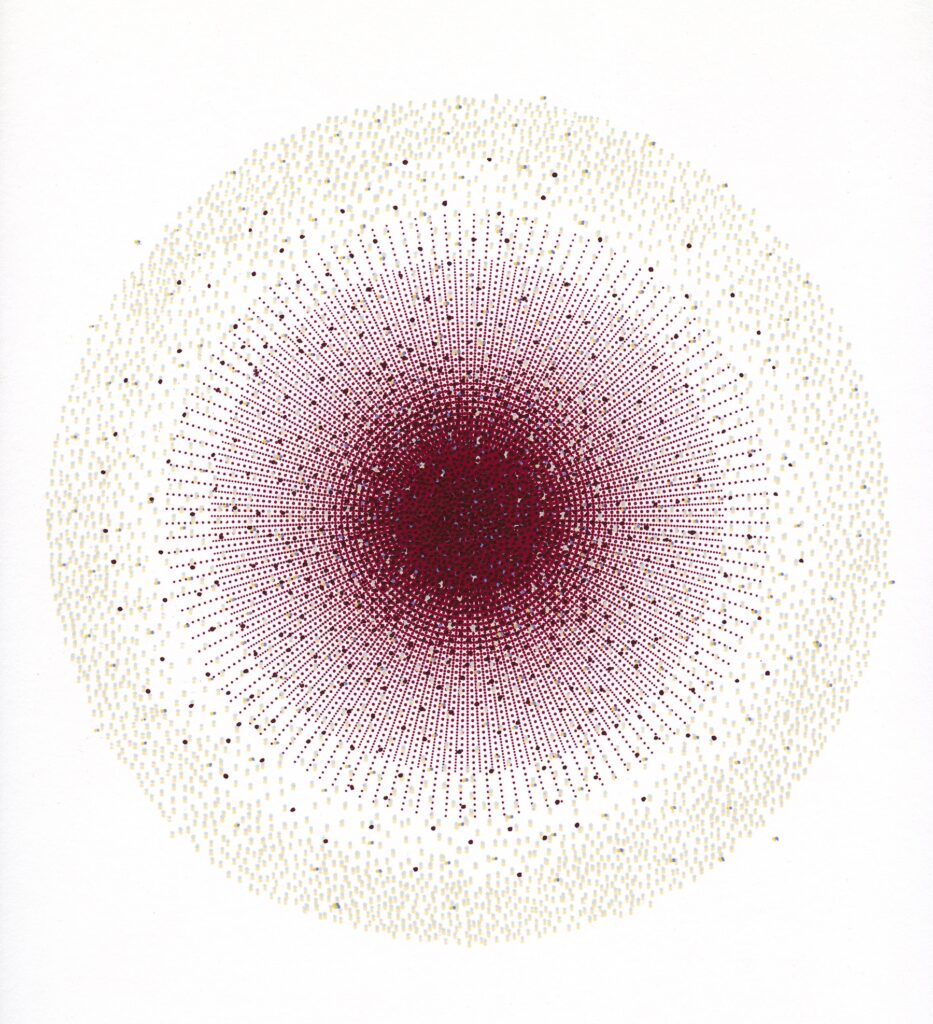

The works in Pulse Systems are silkscreen prints, roughly A3. Each has a singular central circular shape comprised of a patterning of coloured dots. They recall mapping systems and in addition to eyes suggest data, micro-views, and macro galaxies.

The silk screening process (also called serigraphy) that Richter employs involves pressing pigment through a tightly woven mesh in multiple layers, allowing for rich detail and precision in the final image. Richter’s artworks begin with six interchangeable base matrices (arrays of mathematical numbers) that are combined, stacked, rotated, and reordered to generate visual effects. These configurations are then translated into multiple layers of silkscreen printing onto sheets of Fleur de Coton. This procedural logic both structures Richter’s images and informs the titling of each work. For example, in Pulse 6 (2.4.4.6.6.5), the order of numbers indicates the order in which each of Richter’s digital matrices were combined before being printed.

In lieu of framing, Richter suspended multiple works behind clear acrylic panes, each fixed to the gallery’s white walls with tacks. The gold coloured tacks, though discreet, added a conspicuous, metallic edge to the exhibition. This accented and echoed the digital, machine-vision quality of the works themselves. Rather than enclosing the artworks in the manner of a frame, this mode of display allowed Richter’s prints to breathe into the gallery and reflected a kind of collaboration or permeability between the art and its environment.

Renewal (2019), a video work, was projected through one of the acrylic panes onto the wall behind it. This work was composed of semi-transparent shapes illuminated in bright, almost neon, colours. Fabulous round orbs trailed in lines and spirals. They squirmed and circled and flexed, completing a swirling choreography in ninety second loops. The slight gap between the pane and the wall produced a subtle, holographic-like effect for the video. This introduced dimensions of optical depth and dematerialisation, and tied aptly with the artist’s post-digital theme.

Richter’s compositions are acts of repetition, pixelated units recur like spokes on cogwheels, grinding through planes of screen-printed ink and colour onto the page. They are organic marks, owing to their silk-press and hand painted details, but mechanical too: precise and recursive. The visual surface of the resulting works offer a shifted centre and no clear figure-ground relationship; instead, they churn systematised, logarithmically harmonic noise. The circular, concentric matrices seem to shimmer with simulated fluidity, yet their rhythm is mechanically still. They give the impression of not flowing but ticking, expanding, and contracting. They seemed to resemble digital processes caught mid-loop: glitched, frozen, excessive, yet self-contained.

In turn, Richter’s work does not (only) represent the post-digital, nor critique it: it performs it. It makes visible its own systems of code—the visual structures that shape how it is produced, saturated until their aura is broken down. This is the condition of the post-digital: not the presence of digital media, but the inculcation of it, its sedimentation into material form. Moreover, Richter’s works point to a world that can only be endlessly reprocessed and reshuffled. In this future, art would have no true novelty: only permutations, a closed circuit of signs, where something new means the rearrangement of existing components. There, the creation of innovation is replaced by reconfiguration.

If the post-digital condition is marked by copies without origin or reality, Richter succeeds in engaging with it, without resignation nor complicity, but with exceptional observational acuity. Her work does not lament the post-digital’s appropriation of contemporary culture but illuminates its mechanics. Through her fusion of silk-screen printing and digital matrices, she captures the iterative logic of a simulation while asserting a material presence. She reintroduces materiality, labour, residue, texture, and visual attentiveness, inserting the artist’s hand in a space that privileges frictionless and ironic detachment.

Post-digital art can become trapped in recursive gestures: remixing, referencing, and reformatting. Pulse Systems offers a welcome disruption. Richter’s work counters this tendency with a procedural sincerity, treating the logic of digital systems not as a reference source but as a structural tool. Her matrices aren’t an exercise in recycling, but a summons to audience participation in the form of investigation and decoding. Pulse Systems engages recursion as a dynamic and living condition, using interference, variation, and texture to develop a visual language that feels both mechanical and intensely human. Richter has crafted a careful and thoughtful exhibition: intellectually engaging without being obscure, and visually compelling without relying on spectacle.

Alma Aylmore is a Masters student in Museum Studies and Art History at the University of Queensland, with an undergraduate background in Anthropology.