Alana Hunt: Surveilling a Crime Scene (and other examinations), currently on display at Griffith University Art Museum, is a compelling exhibition. Featuring a combination of video, photography, debossed works on paper, sound, publications, and archival documents, the exhibition assembles a rich body of material that testifies to the violence embedded in non-Indigenous existence. Focused on the artist’s experiences on Gija and Miriwoong Countries in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, Surveilling a Crime Scene (and other examinations) offers an intimate scrutiny of the foundations of colonial Australia.

This review focuses on Hunt’s deliberate unpicking of the contemporary, settler-colonial everyday in her video Surveilling a Crime Scene (2023), which anchors the broader exhibition. Located at the rear of the gallery in a darkened, cinematic space, the video is layered with Hunt’s rhythmic narration, and is captivating in both its delivery and aesthetic.

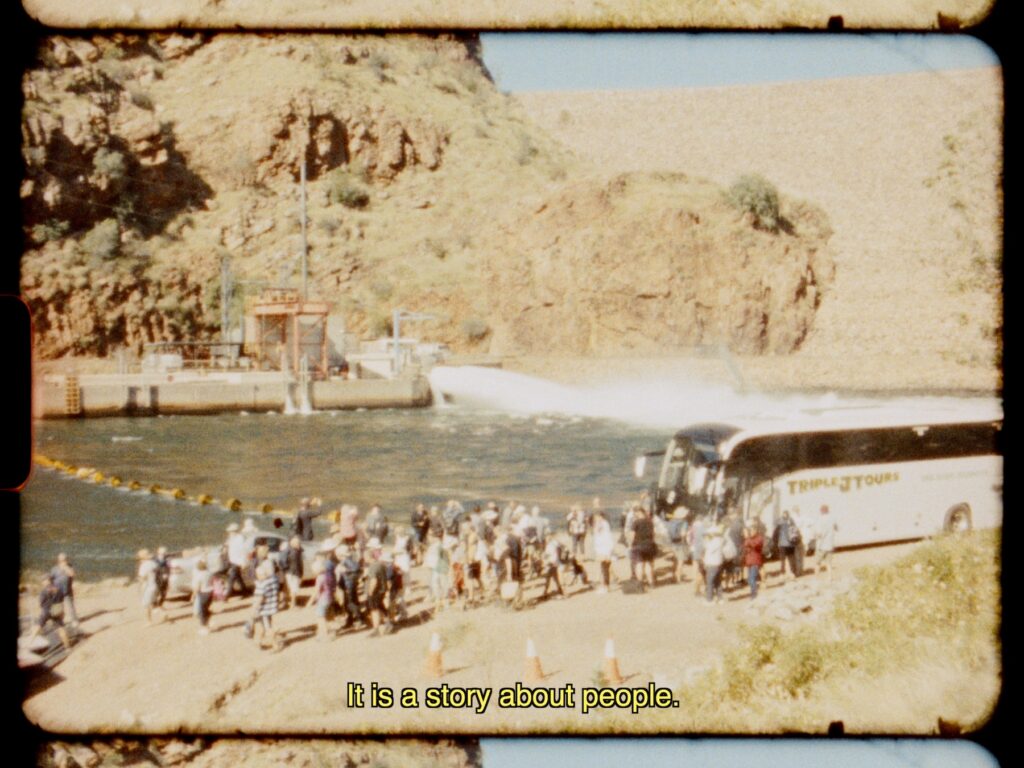

Composed of Super 8 film, an analogue format known for its dreamlike and nostalgic visual quality, Surveilling a Crime Scene’s single-channel video is projected onto a large screen. It flickers through vignettes: goats, plantations, mine sites, blue heeler dogs, dam walls, explosions, swaying grass, and countless other glimpses of life in the town of Kununurra and surrounds. Occasionally, the video features human figures engaging in recreational activities like kayaking, jogging, or visiting scenic lookouts. These scenes shift rapidly, accompanied by Hunt’s voice—subtitled on-screen—guiding the viewer through a poetic and, ultimately, damning reflection on non-Indigenous presence on stolen, fractured, and exploited lands. While her spoken phrases and recordings of Country can stand alone as lyrical fragments, together they form an incisive and confronting account of colonisation as a continuing, everyday reality.

Throughout the video, Hunt often states what the work is not about. She says it is not about “the intergenerational power and wealth and exploits of a few white men” but instead about “you and me.” This direct address calls on the viewer to consider their own daily acts of colonisation. In doing so, Hunt separates her work from the sometimes abstract or distanced approaches of ethnographic films, and instead places the burden of guilt and accountability squarely on non-Indigenous viewers.

At one moment, Hunt says, “Sediments of time seep into the present. Into things. Into us.” This prompted me to consider the gallery as a container for colonial complacency and its material entanglement with extractive practices. While viewing Hunt’s film, I wondered:

- To what extent is Griffith University’s campus, and by extension Griffith University Art Museum, powered by coal?

- How were the gallery’s concrete floors fabricated, and where were the raw materials sourced?

- Do the exhibition’s building consumables (steel projector brackets, screws, nails) come from metal ores extracted from Indigenous lands?

This material questioning could go on, and is not unique to Griffith University Art Museum. Everyday personal acts—living in a house, wearing clothing, working, seeing a doctor, eating foods—carry concealed but devastating consequences when enacted on Aboriginal land. Hunt’s critique implicates both action and inaction in daily life.

Importantly, this conclusion is not new. First Nations people have expressed this reality since the first moments of European invasion. The questions, then, are what makes Hunt’s work distinct? and what gives her non-Indigenous perspective weight and value? Zooming out to consider the exhibition holistically, I would argue it is the combination of three key elements, including Hunt’s direct and personal address to the viewer, her combination of archival imagery with new footage, and her relational, research-based practice. Together, these elements form a deeply considered exhibition. When viewed in dialogue with Hunt’s surrounding artworks—particularly Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven (2020–21) and A Very Clear Picture: A collection of work, words and sources (Vol i and ii) (2023)—it becomes clear that Surveilling a Crime Scene is strengthened by its self-reflexive use of bureaucratic documents. In Hunt’s hands, these are not tools of the system but instruments turned against it.

The relational and research-based grounding of Hunt’s practice is evident throughout the exhibition. Hunt presents information and facts, using both nostalgic aesthetics evoked by the ‘home video’ quality of her Super 8 film, in tandem with archival materials to support and deepen viewer engagement. While Hunt, as a non-Indigenous person, remains an intruder on Country, her documentary-like video does not repeat filmic conventions typical of the Australian landscape. Rather than using the Super 8 camera to understand Gija and Miriwoong lands in a way that might re-inscribe colonial voyeurism, she turns the lens toward specific examples of colonial intervention. This shift from a sentimental imagining of a pre-colonial landscape to a stark view of industrialisation allows the work to avoid romanticising or further exploiting the lands it depicts.

Hunt has worked in a hyper-localised context for this project, focusing specifically on Kununurra and its surrounding areas. Yet the underlying questions and provocations of her work resonate beyond this locality. Her invitation to reflect on complicity, extraction, and presence is applicable across Australia. In Queensland, for example, large-scale mining, exploitative tourism, unsustainable industrial development, intensive agriculture, and poor water management mirror many of the issues raised in the video.

As the nation approaches a federal election, the issues raised by Hunt take on renewed significance, with individual voting decisions influencing the trajectory of colonial violence and the extent of harm inflicted on First Nations peoples and their lands. Surveilling a Crime Scene (and other examinations) at Griffith University Art Museum is, to this end, a highly relevant and affective exhibition. It is on display for a short time, until 17 May 2025, and I encourage Lemonade readers to visit the Museum and engage with Hunt’s powerful and necessary reflection on how colonial power, in both its macro and micro form, shapes contemporary life.

Madeline Brewer is a curator and program producer. She works on Dungibara Country in Toogoolawah.