A verse from an Anglican hymn: “all things bright and beautiful, all creatures great and small”. This is what is cited at the entrance of Great and Small: Kindred Creatures in Indigenous Australian Art. It’s fitting to acknowledge the importance of animals in religions and cultures around the world. Animals have been companions, a means of food and clothing, and a representation of beliefs. Great and Small exhibits the profound role animals have in Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander cultures, the bonds we have with them and our responsibilities to them.

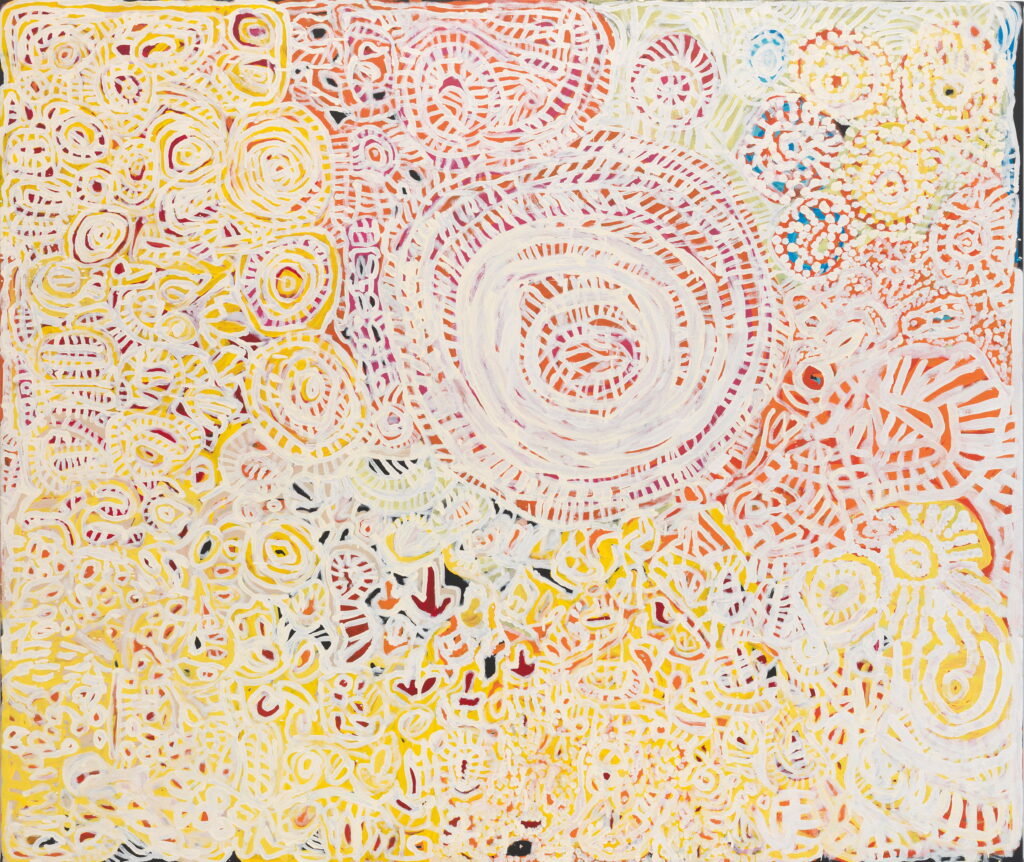

It starts both small and big. The exhibition opens with an area devoted to animals of Creation Stories. A wall of massive canvases greets you, one of them being the vibrant Seven sisters and Tjala Tjukurpa (Honey Ant Dreaming), a 1982 collaboration between Paniny Mick and multiple other Pitjantjatjara artists: Tjungkara Ken, Sandra Ken, Marinka Mick, and Yaritji Young. The multitude of colours, from traditional reds and brown to bright blues and greens, set the scene for the rest of the journey through the gallery perfectly. It’s a mix of old traditions and evolving modernity. Its neighbour is the award-winning Kanyalakutjina (Euro tracks) 2011 by Pitjantjara artist Dickie Minyintiri, stark opposite with its pastels and whites.

There are plenty of widespread Dreamtime stories that change depending on who is doing the storytelling, whether that’s how the Rainbow Serpent carved valleys and rivers or how the emu lost its flight. The winding pastel serpents of Wanampi Tjukurpa (2010) by Pitjantjatjara artist Kunmara Tiger contrast spectacularly with its neighbour, Karrgin and Goolarbool (Moon and snake Dreaming) (2002) by Mabel Juli of the Gija peoples. The latter’s neutral brown tones depict a completely different shape of snake, laying prone under the moon and an accompanying star. The variance in the paintings bring a sense of comfort that people from different places and different mobs can still express a similar sentiment through art.

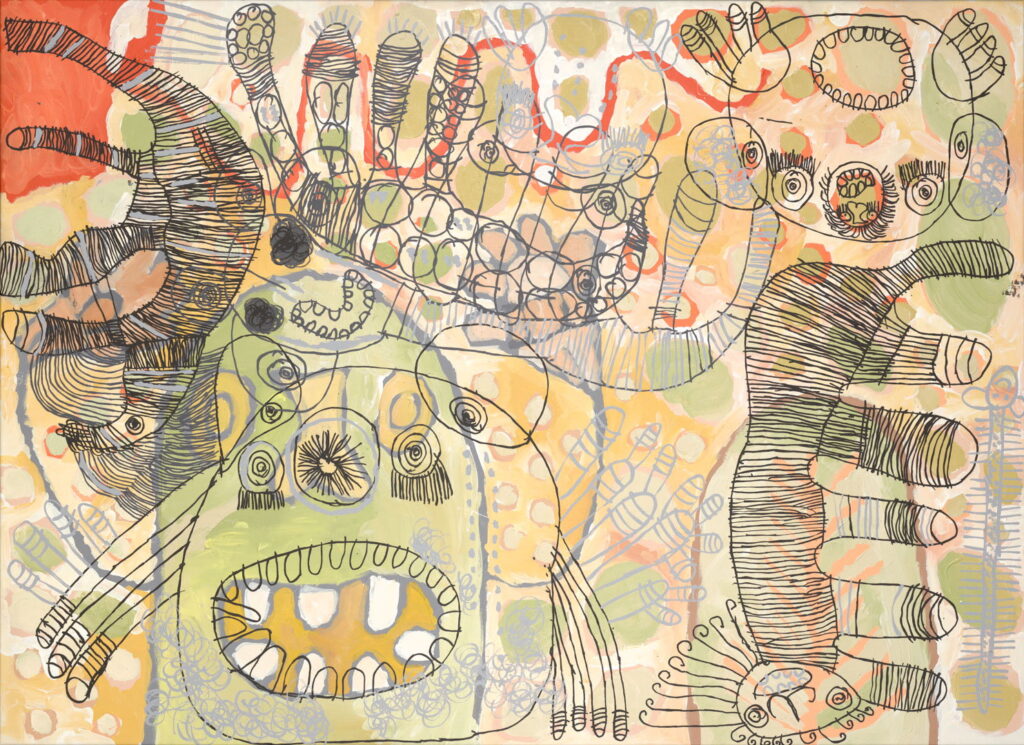

The sustainable hunting practices of Indigenous Australian cultures have ensured the continued survival of many species even as they are used for food, clothing, and shelter. Hunting partners with gathering bush tucker, which also makes an appearance in the aptly named section ‘Good eating’. The creativity is astonishing; there are carved earthenware and pottery, a woven basket decorated in genuine echidna spines, and a gorgeous woollen doll by Luritja artist Rhonda Sharpe called Woman with bush tucker and goannas (2018). As the name suggests, the woman made of recycled wool blankets, natural dye and acrylic yarn drapes a vine of bush tucker over her shoulder as she holds up her bounty of two large goannas. Goannas make a reappearance further into the gallery, where a canvas by Lama-Lama artist Doris Platt presents Goanna skin (2008), a polymer paint rendition of stretched goanna skin, scales and all.

While the use of many different animals for food is celebrated, it’s important to remember that it’s forbidden for individuals to eat their totem animal. The relationship between a person and their totem animal is sacred and can carry deeply personal stories. Thaynakwith artist Thanakupi depicts Creation stories of the Thugganh tribal brothers, who work jointly with animals such as crocodiles, fish, and kangaroos to build sandhills and waterholes, on earthenware tiles titled Tribal brothers (1982). A few steps away from the tiles is the eye-catching Waterbirds, a 2002 artwork by Rahel Ungawanaka of the Aranda, Arrernte, and Luritja peoples. There is so much loving detail in the distinct colours of the mountains, the riverbank, the water and the crisp white birds that live among it. You can’t help but feel how tangible the artist’s relationship with their totem animal is.

Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders also have a connection with non-native animals, both ‘wrangled and ridden’. Stock and working animals such as cattle, sheep, horses, and camels have lived and worked alongside us on missions and homesteads for years. Mission Days (2002) by Aranda, Arrernte and Luritja artist Irene Mbitjana Entata, depicts an overhead view (not quite bird’s eye) of a community in the central desert west of Mparntwe, or Alice Springs, which was run by a Lutheran mission from the late 19th century to early 20th century. It’s a busy scene and the horses fit in just as much the hat-wearing workers, pulling carts and carrying children for indulgent rides. Iritja (Early days) (2013) by Pitjantjatjara artist Niningka Lewis shows a scene with less people. A small group travels with horses on a road bound for a camp which includes a fire, a truck, and rounded up and fenced off flock of sheep. The permanency of the wood burnings on plywood is emphasised by the acrylic paint; the sheep are a shock of white while the horses are burned in to be as everlasting as the people.

On the nearest adjoining wall from these paintings are a pair of engraved bull horns in a case. They are attributed to the Cherbourg Aboriginal Community. On these horns, a man armed with a spear and an emu face away from each other, almost oblivious to the other’s presence despite being carved close to the base of each horn.

Perhaps the cutest section of Great and Small is the one devoted to camp dogs, often called ku’. The significance of ku’ in Indigenous communities starts with an explanation of the concept ‘three-dog night’. As hot as the desert is in the day, the night saps it of all warmth. The coldest desert nights are called a three-dog night, when you need three ku’ in your bed to keep warm. The appreciation for ku’ is expressed in both wooden and woven sculptures, endlessly standing vigilant. Scratching ku’ (2010) is a carved milkwood sculpture of a ku’ taking a moment to itch its face with a chunky front paw by Wik-Mungkan artist Roderick Yunkaporta. You can see the ku’ from other parts in the Queensland Art Gallery, watchful of the animals and stories they protect.

It’s comforting to admire art dedicated to something inherently innocent and natural such as human connection to animals. These kindred connections have existed for a long time, and will continue to exist for much longer, as will the art we make to honour them.

Kyrah Honner is a writer and editor of Birri Gubba and Luritja First Nations descent, based in Meanjin.