A piece of seaweed floats in the ocean. Buoyed by the waves, it furls and unfurls, the tendrils curling in and around themselves creating nebulous patterns. Eventually the seaweed bakes under the sun, sinuous forms solidify as the fronds dry out and stiffen.

I am at the opening of Motoko Kikkawa’s fifth solo exhibition, Drawing with Drone. These biomorphic, fluid forms are evoked again and again throughout the exhibition. I am lucky to speak with Kikkawa, and as we walk around the gallery, she describes observing a piece of seaweed while sitting on the beach. She uses her hands to demonstrate its movement, her fingers flexing and curling to illustrate.

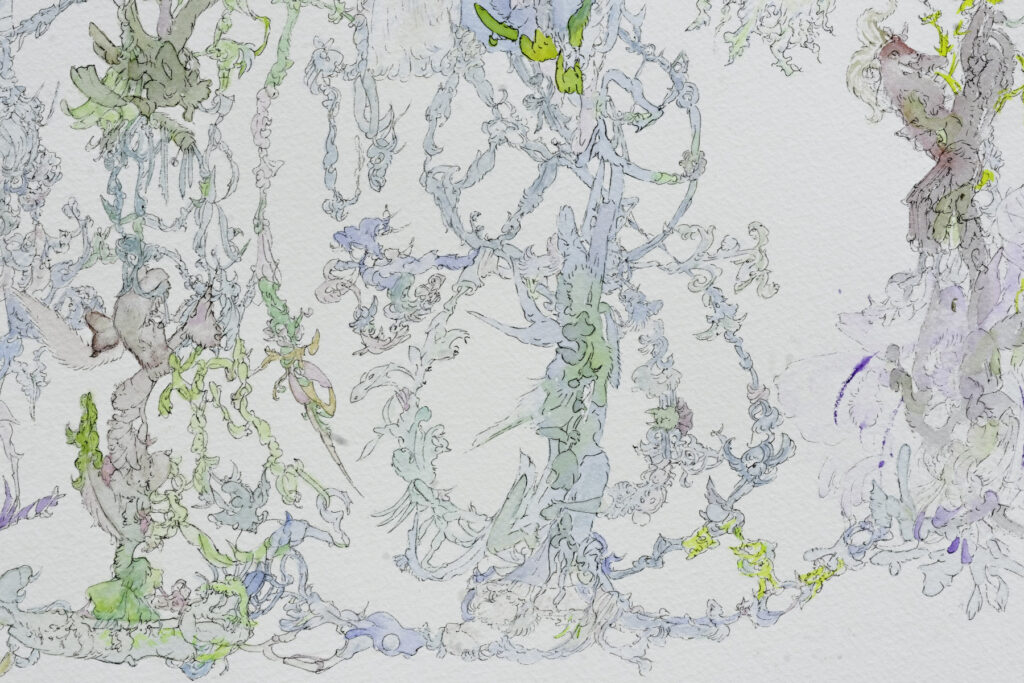

Maybe I’m getting lost in the poetry of it all, but I can’t help drawing parallels between the influence of the natural world on Kikkawa and her material process. Kikkawa begins with free-flowing watercolour, which dries into patterns that she traces and defines with pen or pencil. The linework is delicate, controlled, yet so full of life and movement that each stroke seems to be in motion. I feel like I am looking at botanical illustrations from another realm.

Kikkawa is a multidisciplinary artist who grew up in Tokyo and moved to Ōtepote Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand, over two decades ago. Her practice spans drawing, painting, paper cutting, and installation; as well as vocal and violin performances. Drawing with Drone showcases Kikkawa’s distinctive style of mark-making. Her works on paper line the industrial gallery space of KEPK, ranging from illustrative outlines to more experimental swathes of colour.

We stand in front of her artwork Untitled #7 (2024) and my gaze meanders around the curves of linework and blooming watercolour. It acts as a Rorschach test and, in my mind’s eye, apparitions take shape: a seraphim, a flower, a pig—each dissolving upon further scrutiny. Looking at Kikkawa’s work can feel like reading a map within a dream: there is a sense of narrative yet it feels just out of reach. When I mention this to Kikkawa, she explains that she is heavily influenced by Surrealism. Much like the twentieth century Surrealists, Kikkawa uses an automative approach, intuitively tracing the patterns in the watercolour ground. Her sinuous linework and admiration of nature also reminds me of sketches rendered by Art Nouveau practitioners such as Alphonse Mucha and Hector Guimard. Indeed, Drawing with Drone is host to a melding of many different influences. Untitled #3, #4, and #5 (2024) seem to mimic the vertical flow of sinograms, evoking the aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy. This cross-cultural confluence is one that Motoko Kikkawa performs well. Her work is both original and distinctly intimate.

Kikkawa occasionally departs from her free-flowing style in Drawing with Drone. Untitled #9 (2024) is a smaller work that comments on the housing crisis in Dunedin; here geometric lines break up washes of colour. This is not the sole work by Kikkawa with a political subtext. On the other side of the wall, she presents an artwork about the war in Gaza, explaining: “My parents grew up in Hiroshima, right? So I’m thinking about war all the time.” In this work, her usual washes of colour and intricate linework glide amongst a dull, grey cityscape. Colourful plumes of paint rise up from between the buildings, symbolic of hope.

Another work that reveals Kikkawa’s sensibility hangs close by. The linework in Untitled #15 (2024) is dense, each form inextricable from the whole. Kikkawa mentions that she was thinking about mycelium when making this work. Mycelium, the network of fungi running underneath the ground and distributing information to the entire ecosystem, has become a widely understood metaphor for inter-relationality. Kikkawa taps into this symbology, musing that, “We are all connected, sometimes supporting each other, sometimes fighting each other.” Black ink fills the negative space of this artwork, accentuating the vivid colours that swirl together as one amorphous creature. Like most of Kikkawa’s work, I have the impression that I am looking at something of this world. Yet whether I am observing it through the lens of a microscope or at a great distance is unclear.

When I ask Kikkawa about the exhibition’s title—Drawing with Drone—she tells me about an experimental process she has been trialling, which will be performed as a part of the exhibition. Forgoing the more traditional techniques that she has employed throughout the body of work discussed, Kikkawa’s performance involves using a drone as a drawing implement. Naturally, this requires a certain level of surrender regarding the end result. It is interesting to consider how technology is being used in this instance: not to mediate an unpredictable outcome, but to emphasise it. Kikkawa’s ability to welcome the unexpected by not just allowing mistakes, but actively inviting them, really stands out to me. She explains: “The big rule is saying yes all the time.”

Motoko Kikkawa’s embrace of the imperfect, her willingness to allow her works to unfold before you in unexpected ways, feels fresh. In a time when artists must grapple with their place amongst generative technology, Kikkawa has found a way to maintain the humanity of her work while also embracing technology as a collaborator. Drawing with Drone is a reminder of how the hand of the artist, made visible through mesmerising gesture or executed via drone, can never be replaced.

Katharina Ganster is an Austrian-born artist and emerging writer living on the lands of the Jagera and Turrbull people. She is currently completing her BVA at Queensland College of Art and Design.