There are so many pleasures in visiting international galleries. Sometimes the pleasure is in the experience of seeing a long-known work in the flesh; other times it’s the discovery of something new. In Mexico—a country I’ve been lucky to visit every few years (with thanks to an adventurous sibling)—stepping from the uneven pavement, dangling electrical wires, and heaving sounds of a foreign street into the white cube is akin to stepping from the unknown to the known. Despite not speaking Spanish, the ebbs and flows of a gallery are familiar. Here, just as in Brisbane, they share cloakrooms and white walls, hushed audiences amidst selfie-taking influencers, incomprehensible wall texts, and languorous invigilators. This review (of-sorts) moves through some of the galleries of the past few weeks.

Museo Tamayo’s Paradoxes of Internationalism (as narrated by the Museo Tamayo Collection), Part I provides an ideal starting point. Sitting quietly at the edge of Mexico City’s sprawling Chapultepec Park, Mexico’s first international art museum is a low-slung building of concrete and marble. Inside, shafts of sunlight stream through to a central atrium and irregularly-shaped galleries with unexpected ramps and staircases wind you clockwise from entrance to exit.

The Paradoxes of Internationalism brings together lesser works by known artists (Mark Rothko, Jean Dubuffet, Tacita Dean, Shirin Neshat) with artworks by and artefacts about the gallery’s founder (Mexican artist, Rufino Tamayo), and less familiar Latin American names. Shades of grey, concrete, and charcoal dominate in works that are neat and restrained. Against this material heaviness, a final room lined with (fake?) green shrubs and excerpts from Yto Barrada’s Guide to Trees for Governors and Gardeners, 2014, lifted the mood. The ‘hypothetical manual’ provides 1984-esque guidance for a city receiving a high-ranking diplomat, with instructions on where to direct funds and cost-effective methods for hiding a city’s less pleasant realities. In light of Brisbane’s forthcoming Olympics, mingled with memories of living through Sydney’s earlier turn at host, the darkly humorous work treads close to reality.

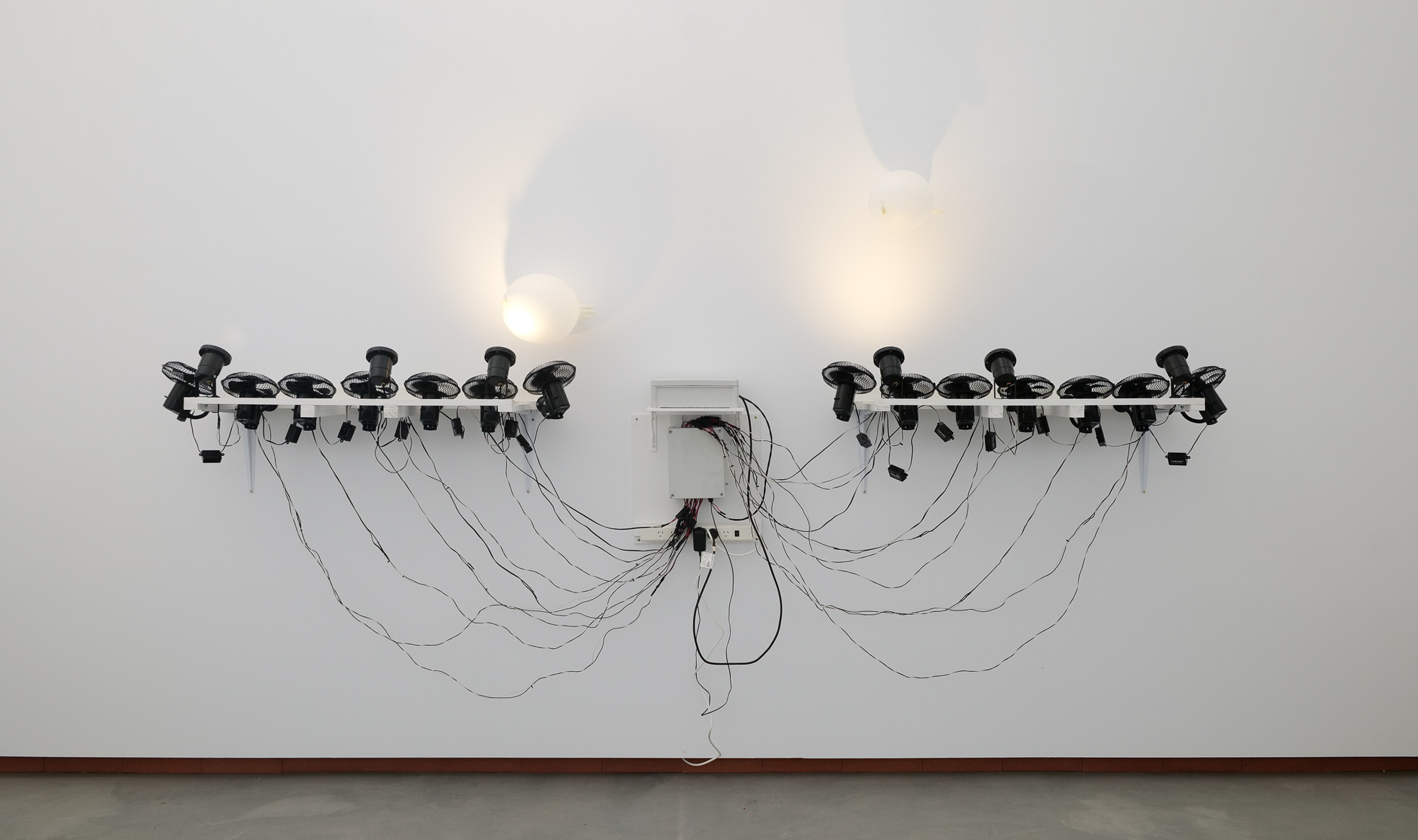

Internationalisms, understood either as shared artistic concerns or traversing national boundaries, continue in Jannis Kounellis: In Six Acts at Museo Jumex and Daniel Guzmán: the man who should be dead at commercial gallery, Kurimanzutto. The solo showcasing of the Italian Arte Povera artist illuminates a consistent visual language of surprising balance and harmony across installation works of diverse scale and forms. Stand outs included his repeated use of dislocated white marble busts: layered amongst a stone wall, set atop a beautiful period-piece table, and sitting on a wall plinth within a larger poetically-drawn line; and the artist’s sculptural use of soft, insubstantial materials: blackened soot in regular patterns, piles of ground coffee. At Kurimanzutto, Guzmán’s work also explored the materiality of art installation aesthetics, hanging 2D works on large and exposed timbre scaffolding (mimicking the exposed timber of the exceptionally stunning gallery space, a former logging yard) and more explicitly engaged with figuration. The work felt like a transcription of disturbing and hyper-symbolic dreams, rendered by an artist with a Modernist’s appreciation for flatness and confused perspectives, and a contemporary artist’s palette.

Against these spaces, Mexico’s “local” scene condenses in the figure of Frida. Reduced to a mono-brow, flower crowns, arms crossed holding a cigarette to her lips (and sometimes, bizarrely, collaged onto a naked body not her own), Frida repeats ad nauseam. Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo cashes in on this fame.

The museum-house-gallery is three small yet multi-storied buildings in the south of the city. One sports a ridged roof (borrowed and scaled up by Museo Jumex into its defining architectural feature) and all three are fenced by cacti. Compared to the multiple buildings and bursting holdings of Kahlo’s Casa Azul, which gather around a lush courtyard and hold the city at a distance, Estudio Rivera is strikingly modest, sparse, and small; the boundaries between it and us easily slipped through.

Throughout the Museum’s buildings, despite the joint title naming Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo, Kahlo is strangely absent. Rivera died only 3 years later, yet he was 20+ years her senior. Black and white photographs of him as an older man, scattered throughout the house, reiterate his longer-lasting presence: not internationally (no artist quite reaches the fever pitch or global recognition of Kahlomania) but within this context, within their lives, he literally and figuratively looms over her.

The version of Rivera put forward by the museum is, interestingly, neither muralist nor political artist, but creative figure embedded within local, international and interdisciplinary scenes. The opening room is barely filled out with a suite of seats, a gramophone, and the first of multiple listening stations, establishing Rivera as the host of weekly recitals. His double-height ceiling’ed studio displays a wealth of pre-colonial objects, small Mexican-scene paintings by Nahui Olin, and extraordinary street puppets and skeletons, which both decorate the walls and hang uneasily over visitors, inert and waiting to be activated. It’s unclear which, if any, Rivera created. Modern furniture with sleek geometric lines in a subdued jungle green and exhibits dedicated to the building’s architect carry across the buildings, rounding out this vision of Rivera.

Less overtly, the museum establishes a picture of modesty: rooms are exceptionally small, a single pair of Rivera’s well-worn shoes are unpretentious. I imagine both Rivera and Kahlo moving with unease up twisting stairwells and into cramped rooms, noting the striking discrepancy between these figures of wealth and Mexico’s almost complete lack of access. In a final bathroom barely large enough to hold a bath (and the bath barely large enough to hold a person), the museum shares: this is the location of Kahlo’s What the water gave me (also known as What I saw in the water) (1938). It is the singularly most evocative and convincing testament that the artists were once physically and creatively here: Kahlo as an innovative painter of life’s miseries, Rivera as one of those miseries.

Back in Roma Norte, I stumble upon Galeria OMR. Stepping into the elegant, cool, and darkened space I am swiftly returned to the hyper-present of contemporary art and equally find myself transported.

Above me, an exposed lightbulb swings from the ceiling in perfectly consistent circles. Two pianos sit in opposing corners of the gallery and large white works, pricked with delicate patterns, fill the walls. As I move into the room, the piano to my left starts playing—tentatively at first, repeating one note when I stand still, and bursting into moody and familiar song as I continue. Fresh air flows in from a verdant courtyard beyond and the second piano beckons.

On the far wall of the gallery, a video monitor shows an abstract painting in motion, creating patterns of black and white. It brings to mind Refik Anadol’s AI-generated work and unmistakable allusions to climate catastrophe. As the piano/s continue, I feel as though I am in a movie, the narrative sits as the edge of my consciousness, tinged with thoughts of Edgar Allen Poe and Lars von Trier’s Melancholia. It comes out of thin air, spreads, shifts, becomes something else is the gallery’s first solo showcasing of Pablo Dávila, inspired by Inger Christensen’s poem “It” and thoughtfully bringing together the artist’s diverse engagements with site specificity, musical immersion, digital art, and works on paper. Via his monochromatic aesthetics and everyday objects, Dávila effectively draws attention to the heightened emotions and imaginations made possible in the context of experiencing contemporary art. It is nothing short of delightful, and confirms without hesitation or boundary the pleasure of being an art critic.

Leaving the gallery, I reflect: Mexico’s art scene is dazzling, overwhelming, and rejuvenating. And after a decade of visiting this city, I’m still yet to scratch the surface.

Louise R Mayhew is an Australian Feminist Art Historian and the Founding Editor of Lemonade.