Whimsy is not a word I typically associate with electronics. I don’t easily tie it to Saturdays at Bunnings, tinkering, retrieving assorted pieces of wood from under the house that might come in handy one day, masculinity, and hard yakka. Nor is it top of mind when I think of the Renaissance and religion. Yet all of this circulates in Ian Burns’ latest series of works, Whose Body, What Mind | What Body, Whose Mind, at The Renshaws.

Although I only have a passing familiarity with Burns’ practice, his work is immediately recognisable. His sculptures bring together electrical cords, light bulbs, small electric fans, monitors, and clever wooden scaffolds. They are roughly human size. His cords are always on display, negotiating an aesthetic of tidied mess. Similarly his wood-work strikes a balance between amateurish—there is no fine joinery craft here—and practical, balanced, neat construction. Moreover, his works always do something.

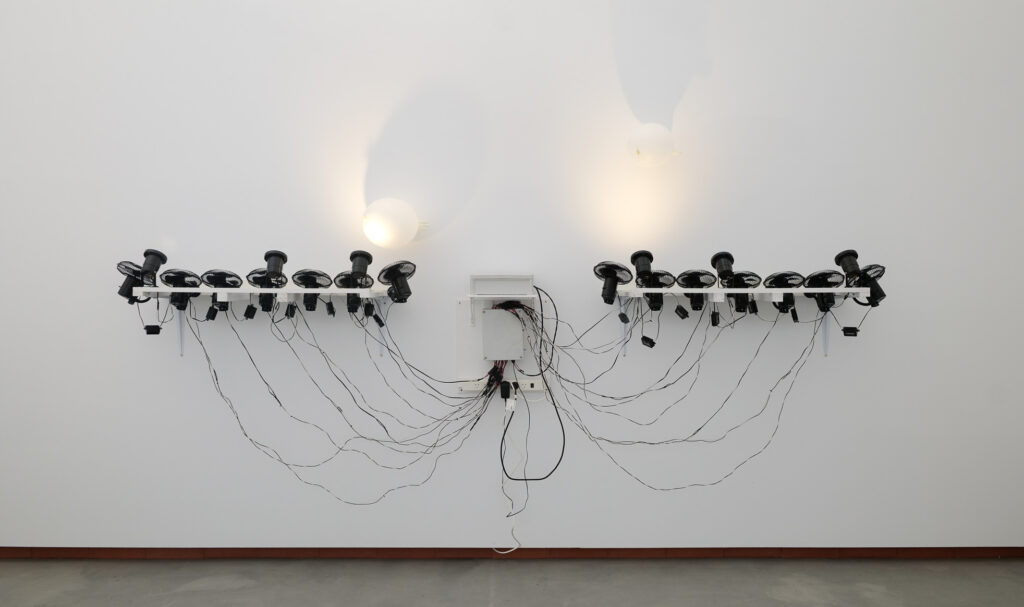

In From the other side (2024), a pedestal fan swings back and forth from one monitor to another. As the fan blows on each, it also activates a video, endlessly transforming the respective still portraits of a sitting woman and man by appearing to blow their long wavy hair. In How it started (2024), Burns excerpts the central motif from Leonardo’s The Creation of Adam (1508–1512). Standing near this work, the outreached index fingers of two golden hands spring to life, moving toward one another and sharing an electric spark. There’s something Monty Pythonesque in this set up, with its carnivalesque animatronics and lo-fi set design. For Speech (2024), Burns places two rubber boots atop a small suite of wooden footsteps. As Danielle Renshaw generously led me through the exhibition, Speech interrupts our conversation with jaunty puffs of smoke. Winged Victory (2024) deploys two sets of seven small rotating fans in order to keep two gloves—filled with air like make-shift balloons or strangely overblown hands—in the air. Finally, Cadence (2023) lines up 25 electric bulbs with magnifying glasses to cast golden lines on the white gallery wall. As the lines move, they evoke the walking man of pedestrian intersections. It is these fruitless actions—turning video monitors on and off, moving and resetting sculptural parts, puffing smoke rings, keeping objects afloat, and creating pictures from light—that give Burns’ works their sense of whimsy.

What’s especially enjoyable about Burns’ work is its ability to welcome us in with these easily understandable operations, and then to tumble in multiple directions according to audiences’ diverse knowledge and interests. Danielle shares stories of children who delight in front of the works’ movements, easily tuning in to their patterns, and scientists who recognise in Burns’ works demonstrations of physics and airflow. I imagine another subset of audiences, makers themselves, enjoy unravelling how each sculpture functions, tracing the mechanical interactions of their parts and perhaps envisaging how they might do things differently, with programming and circuit boards. All of Burns’ processes are analog. Finally, Burns himself nudges us in the direction of symbolic interpretation, asking us to find meaning in his artwork titles and allusions to Adam and Eve, God, men’s work and heavenly wings. More broadly, Burns showcases an artist’s labour as physical work, exploration, and play; and creates a space for audiences to prioritise seeing, thinking, and being in the unique locale that is the white cube. His work conjures the old mantra of art for art’s sake, and it’s strikingly refreshing.

Experiencing Burns’ work in tandem with a welcome conversation with Danielle, I keep returning to the thought that Burns and The Renshaws are a perfect pairing. His strange, electronic sculptures feel like they were made for, indeed they were made for The Renshaws’ slick, part-Industrial, part-on-trend-interior-designed white cube. The artist constructed each of the works within a three-week residency for the exhibition, working up until the opening. Both Burns and The Renshaws also operate in a highly-unique relationship to the Meanjin artscene: less visible than some other artists and galleries yet inter/nationally renowned, undeniably cool (or edgy, to borrow a word from a friend), widely respected and warmly loved. Both have strategically carved out their own voice—deliberately eschewing artworld trends and the incessant pace of many gallery schedules in favour of durational investigations (Burns) and relationships (The Renshaws)—and both have strategically placed one foot in Meanjin (with Burns completing his PhD under Professor Ross Woodrow at Queensland College of Art) and many feet more elsewhere (including New York, where Burns is based; Ireland where The Renshaws’ first saw his work; and across Australia via exhibitions and projects). In short, The Renshaws bring to Meanjin artists of world-class calibre, artists we might not otherwise see, and gosh am I glad they’ve reopened.

Louise R Mayhew is an Australian Feminist Art Historian and the Founding Editor of Lemonade.