The exhibition title’s playful reference to the Potterverse characterises Fernando do Campo’s exhibition at Rockhampton Museum of Art (RMOA). Equal parts whimsical and troubling, do Campo’s title conjures the overlapping forms of a bovine-human hybrid unique to Rockhampton. Initiated by do Campo in 2019—three years prior to the launch of RMOA’s new landmark gallery building—Capricornian Minotaurs and Where to Find Them purposefully coincides with Rockhampton’s triennial industry festival “Beef Week.” Running from the 5th to the 11th of May, Beef Week is Rockhampton’s premier tourist event. The 2021 iteration drew over 115,000 visitors to the regional city.

do Campo’s practice is broadly concerned with critical investigating inter-species histories. An academic artist with a diverse theoretical toolkit, do Campo approaches the human impact on plant and animal species as an index for colonial projects, nationalism, and the formation of hegemony more generally. Central to his work is a kind of museological curatorial practice. do Campo treats archival research, critical investigations into institutional collections, social history research and scientific fieldwork observations as procedural mechanisms within his studio methodology, assembling primary source material as a departure point for producing paintings, textiles, and painting-sculptures dense with narrative and referents.

Capricornian Minotaurs and Where to Find Them appears in three sections: loaned archival material related to the Australian beef industry, a major series of painting/textile/sculptures, and a selection of paintings from RMOA’s collection alongside reproductions of the paintings by do Campo.

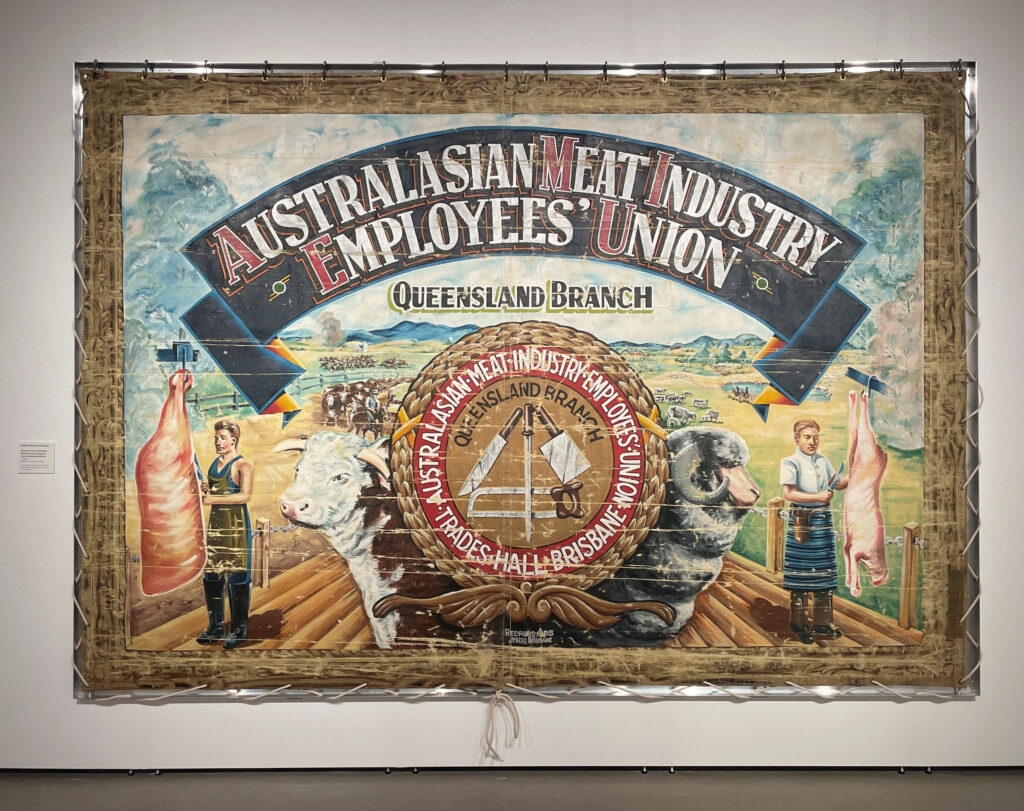

On loan from trade unions, state and local libraries, and the archives of various Rockhampton-based beef industry associations, do Campo’s selected archival material shows us snippets of the pride and power of the meat industry across several historical threads. Most of the material features or has some relation to Rockhampton and its ‘beefiness:’ recognisable buildings, businesses, and politicians are scattered amongst the images of anonymous cows and people. Despite the majority of this material being presented across five vitrines, which fill the floor-space of the gallery, one framed, wall-based protest banner dominates this section.

Produced by the Queensland branch of the Australasian Meat Industry Union, the scale and power of this Socialist Realist-inspired 1940s protest banner colours my reading of the archival material as a whole. Through the spectacle of the banner’s antique dignity, the accompanying black and white photographs—of cattle adorned with ribbons, carcasses, abattoir infrastructure, and well-groomed ladies and gentlemen—are all grounded in the spirit of trade union solidarity and class struggle. Each of the approximately 60 archival items are titled and attributed in an accompanying roomsheet, however do Campo’s diverse and un-notated archival collection resists a conventional narrativisation. What arises in place of contextual information and historicisation are emotive effects: aesthetic links; re-occurring visual motifs; and resonances of the poise, care, and community-spirit of yesteryear.

These emotive resonances provide a backdrop for do Campo’s major series of sculptures. These are eight wall-mounted escarapelas, each named after a member of the artist’s immediate family. Anthropomorphic in scale and form, each is constructed from abstract-patterned canvas paintings layered amongst old school and sports uniforms belonging to the do Campo siblings. do Campo moved with his family from Argentina to Rockhampton as a 14 year old. As he explains, the years of 14 to 17 were an enormously formative period in his life, one in which the do Campo family determinedly embraced assimilation into central Queensland culture.

At first glance, do Campo’s sculptures appear as a nostalgic dedication to this period and place so vital to his family’s history. However, a level of dis-identification is at play in the relationship between do Campo and his subject, the “Beef Capital of Australia”. In his Escarapela Capricorniana series, the young do Campo’s sincere and largely successful attempts at assimilation contain their own seeds of unravelling. Revisiting fond memories of identification with Rockhampton and central Queensland culture, do Campo describes the seams and ill-fitting proportions of his family’s hybridised costume of belonging. Like a prize ribbon strapped to a new car, do Campo’s gigantic escarapelas exaggerate their own superficiality and fragility.

In the final section of the exhibition, do Campo presents, in a salon hang, eight mid-century paintings by white Australian men in the RMOA collection. Chosen for their Cattle-agrarian subject matter, amongst do Campo’s work these paintings are decidedly awkward and anachronistic. Collectively, the paintings represent an ‘Aussie-Outback-Imaginary-Kitsch;’ they are an index of the distorted patriarchal and colonial lens through which Australia attempted, and occasionally still attempts to, perceive itself. Responding to this ‘Outback-Imaginary’ self-image, do Campo has created a mirror reflection of the salon hang with reproductions of each painting in an abstracted, linear-grid rendering. Recognisable as copies of the earlier works primarily through their repetition of scale and salon hang arrangement, do Campo’s reproductions are heavily distorted by his signature rendering style.

In the act of translation, do Campo identifies with and absorbs the ‘Outback-Imaginary’ into his own personal narrative and aesthetic universe, again exaggerating the kitschiness of his appropriated referents through what might be described as dis-identification. Stepping back to take in the two collections of paintings as a single installation, the index of a historical central-Queensland-mythology becomes do Campo’s own personal historical archive, re-distorted and made present again by his reproductions.

do Campo pulls historical material through the filter of his studio practice to produce exhibitions that sit between the conventions of the museum and the contemporary art gallery. By weaving aesthetic links between his works and the material voice of the archive, do Campo’s museological curatorial practice operates more like an appropriation or readymade practice than the ‘exhibition-making’ process of institutional curation. The archive is not displayed as evidence in an argument, presenting a narrative of history, but rather, as an uncovered possibility, an obscure interstice from the past brought into the present.

Llewellyn Millhouse is an artist and arts worker who holds a Doctorate of Philosophy from Queensland College of Art, Griffith University. In 2022, Llewellyn relocated to Hervey Bay as the curator of the relaunched Hervey Bay Regional Gallery.