I flew into the modest-sized Saudi Arabian city of Al-Ula to see Desert X, a temporary open-air art exhibition in the ancient desert region that surrounds the city and seems to go on forever. From the air the terrain’s impressive but once on the ground, it’s a stunning landscape of sandstone canyons, towering pillars of rock, and wadis (dry river beds) with sparse vegetation.

Running parallel with Al-Ula’s old town (a linear cluster of 900 mudbrick and stone houses) is a valley oasis with fertile soil, water and (I read) two million date palms: the reason why human settlement has existed here for 5,000 years.

Knowing very little about the real Saudi Arabia and its art-scene, the Al-Ula location turned out to be enlightening. “This small town is the crowning jewel of Saudi Arabia’s tourism ambitions,” wrote Conde Naste Traveler in 2023. A lot is in development here, particularly ‘cultural tourism,’ and The Royal Commission of Al-Ula is firmly behind it all.

It’s early summer and my first day started cool as I began walking the Desert X site, reaching the low 20s by midday. In this third edition there are 17 artists with 12 from the Arabic-speaking world, but also from Mexico, Italy, Brazil, Ghana, and South Korea. The artists were commissioned to develop proposals after spending time in Al-Ula’s dramatic desert.

Following guidance on how to best tackle the 15 presentations, my first encounter was Monira Al Qadiri’s W.A.B.A.R, five large bronze-black objects. While different in colour and form to the nearby rock formations, these darkly patinaed and noduled sculptures seemed at home, safely landed in the desert sand, perhaps of extraterrestrial origin.

Proceeding both by foot and buggy, it was relatively easy to discover the other works, sometimes found in open valley areas or nestled in ravines, but spread over a substantial site and mostly hidden from one another.

With any largescale site-responsive exhibition like this, the artwork is inevitably in competition with the environment. How well has an artist read, and is their work in sync with, the site? Sometimes—as in W.A.B.A.R.—the work was satisfyingly complementary, at other times nature had the better hand.

As Oxford-based curator Maya El Khalil noted: “Al-Ula is monumental . . . the reality is, human efforts struggle to match the grandeur sculpted here. We challenged the artists . . . to adjust their perspective to encounter the unseen aspects of the place with reverence, attuning to the forces, rhythms and processes that shape the landscape.”

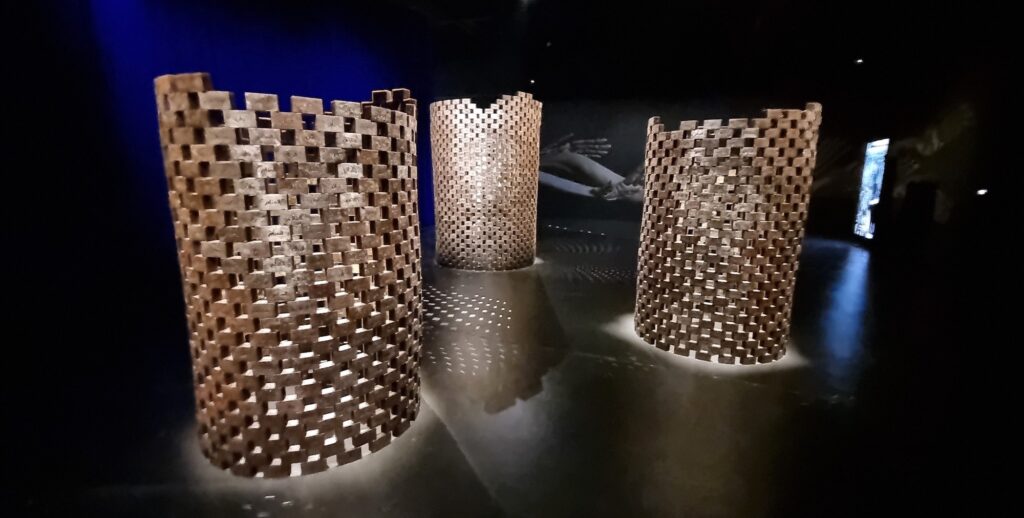

While the majority of artworks satisfied these kinds of criteria, a few that stood out were: Sara Alissa and Nojoud Alsudairi’s Invisible Possibilities: When the Earth Began to Look at Itself, an architectural work in negative form carved into the desert floor, which you could walk down into; Ibrahim Mahama’s monumental Dung Bara—The Rider Does Not Know the Ground is Hot, composed of multiple (over 200 maybe) terracotta pots scattered, upturned, and embedded across the landscape; Faisal Samra’s The Dot, a long line of stacked rocks led to a large, mirrored steel sphere reflecting the surrounding landscape, as well as the viewer; and Rana Haddad and Pascal Hachem’s Reveries, a trio of tall towers of connected, hand-formed terracotta pots that paid tribute to the region’s craft-making.

Desert X AlUla is in collaboration with California’s Desert X, which has had four iterations in Coachella Valley since 2017 and is produced by The Desert Biennial, a not-for-profit company based in nearby Palm Springs. For the previous Desert X AlUla (2022), UAP (Urban Art Projects)—a Brisbane-based company that commissions and builds large-scale public artworks internationally—was contracted to fabricate and install the artworks.

By the way, anyone who watched The Lost Leonardo (2021, Netflix) may have noted that the painting, Salvator Mundi, attributed in whole or in part to Da Vinci, is likely to be housed in a museum to be built by Royal Commission near Al-Ula.

__

A thousand kilometres south-east of Al-Ula lies Riyadh, the Saudi capital. With a population of around seven million it’s a metropolis with huge developments taking place, not least of which is Diriyah: the amazing old mud-brick city sitting on the capital’s northern edge. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Diriyah is where the Al Saud dynasty was established in 1727, and is now the centrepiece of a cultural and lifestyle development.

Taking its name from where it sits, the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale is housed in JAX District, a repurposed industrial area with 100 renovated warehouses, and is Riyadh’s new creative centre with exhibition spaces—including SAMoCA (Saudi Arabia Museum of Contemporary Art)—artists’ studios, and other platforms supporting a growing arts hub.

I was there for the second edition titled ‘After Rain’ (20 February to 24 May 2024) led by artistic director Ute Meta Bauer of international renown. It featured around 170 artworks by 100 artists from 50 countries with 47 new commissions. The title and exhibition speak, the catalogue says, to “revitalization and renewal, calling to mind the refreshing scent of the air when rain has fallen.” Bauer reminds us that this earthy, intense smell is known as petrichor.

The simple idea of After Rain stayed with me over the next few days of viewing the Biennale’s engaging array of beautifully presented art in six spacious halls. The metaphor, however, of renewal after rain in turn raised another, that of washing away the past. Tessa Solomon, in her pithy article on the Diriyah Biennale (ARTNews, 26 March 2024), says: “Incisive art looks, without hesitation, back as well as forward to understand how systems of power fail people and places. That’s not a topic easily broached in Saudi Arabia” (or in Australia at times and many other countries, I’d add). She continues: “art isn’t a cleansing agent; it’s a tool for self-examination.”[1] Conversely, as a tool for self-examination, art can have cleansing power.

Highlights were numerous but included this shortlist of 10 artists and projects representing the range of media and geographic spread of After Rain: El Anatsui (Nigeria/Ghana), Taus Makhacheva (Russia/Dubai, UAE)), Daniah Alsaleh (Jeddah/Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), Christine Fenzl (Germany), Alia Farid (Kuwait/Puerto Rico), Sara Abdu (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia), Sopheap Pich (Cambodia), Reem Al Nasser (Jizan, Saudi Arabia), Arin Rungjang (Thailand), and SYN Architects/Sara Alissa & Nojoud Alsudairi (Riyadh Walking Tours). Three Australian artists were also in the mix: Simryn Gill (Sydney/Port Dickson), Liam Young (Brisbane/Los Angeles/London), and Suzann Victor (Blue Mountains).

Not surprising in the Arab world, poetry is culturally ubiquitous and very present in the thinking of many artists in the Diriyah Biennale. Particular examples were to be found in the nearby exhibition In the Night, at SAMoCA, which offered explorations into the mystery and beauty of the night, with works from 30 local and international artists from France, Morocco, Tunisia, India, Japan, Argentina, Pakistan, Croatia, and more. South Australian, Hossein Valamanesh (1949–2022), was included with a typically poetic work, Constellations 1–5 (2020).

__

Diriyah and Al-Ula are just two of Saudi’s super-projects, all led by the country’s Vision 2030 and the Saudi Crown Prince. One that’s talked about online a lot is Neom and one of its sub-projects, already a viral hit, is The Line, an eco-city for nine million residents: two 500-metre-high linear skyscrapers will run parallel to each other across 170 kilometres. These projects integrate contemporary art and culture and enlist global expertise, including Michael Lynch, an Australian with extensive international arts management behind him, who is now Head of Entertainment and Culture at Neom.Going to Saudi for the first time, albeit for 10 days only, I was struck by the hospitality of everyone I met combined with a palpable enthusiasm for the opening of their country to others, and so enabling Saudi artists to share their stories through contemporary art.

__

Desert X AlUla 2024, two desert sites near Al-Ula and AlManshiyah Plaza, 9 February—23 March 2024

After Rain: Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, JAX District, Diriyah, Riyadh, 20 February—24 May 2024

[1] Saudi Arabia’s Diriyah Biennale Looks to the Future amid an Imperiled Present

Ian Were writes on contemporary art, design, and culture and has recently written short stories. Since 1997 he has edited more than 20 art books and publications, including 12 books as a freelance editor.