Pat Hoffie’s powerful new exhibition is timely in its mounting, almost to the day, with the horrific conflict in Gaza. ‘Conflict’ seems too gentle a word, and of course Hoffie could not have seen it coming, but like the crisis in Gaza, the beginnings of Hoffie’s exhibition reach back through the years. Framing the show with the tragedies of the contemporary world—war, genocide, refugees (of both war and climate), environmental collapse—and media, in this case works on paper, offers a fascinating bracketing of the artist’s work, bookending not a survey but a sequence of the artist’s recurring concerns.

This review of Hoffie’s work is refreshing, both in its deeper exploration of media, and as a (frankly overdue) institutional counterpoint to UQ Art Museum’s earlier exhibition of Hoffie’s art, Fully Exploited Labour (2006), which collected its own sequence of recurring concerns, centring around the not-unrelated geopolitics of global labour and trade, and with a focus on collaborative works. Conversely, This Mess We’re In is comprised of works made solely by the artist. This is notable in the clarity of communication across so many works and a span of twenty years, unmediated by the hands and voices of collaborators. The result is a direct, powerful and surprisingly consistent message.

The exhibition consists of three significant bodies of work, including Ready to Assemble (2003), Clusterfkk (2018–2020), and Smoke and Mirrors (2016), and is neatly encapsulated in the exhibition publication by the artist as being: “drawn together by two shared aspects: 1. They’re all works on paper, and 2. They all address some form of cataclysm, crisis, punctum, mess.”

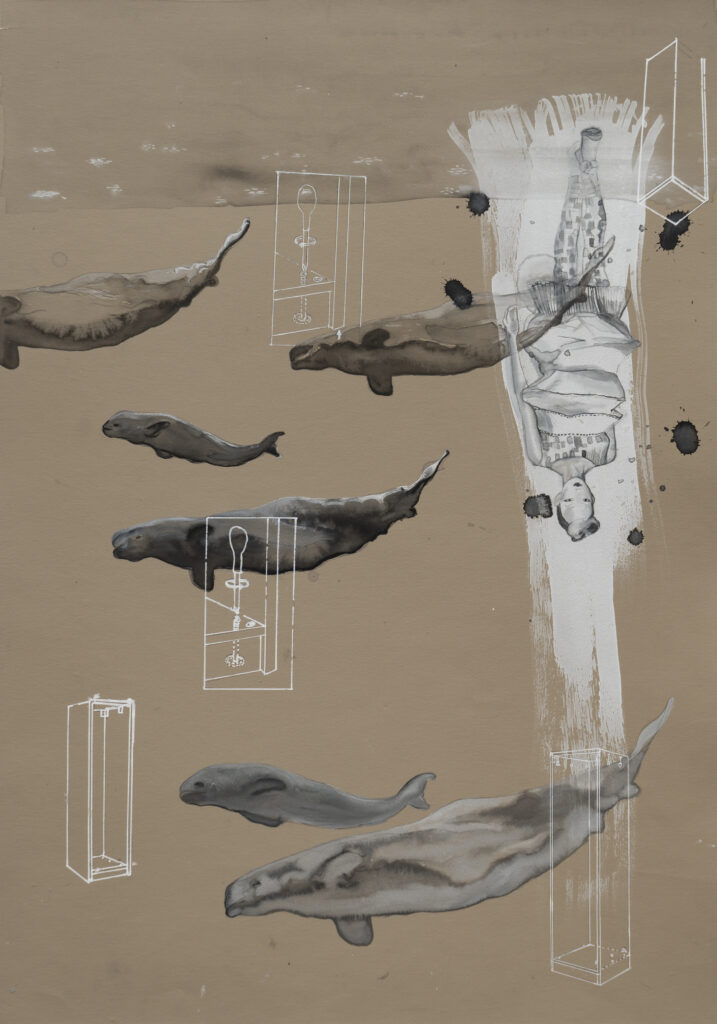

Ready to Assemble (2003) is the earliest of the series and the first to be encountered in the exhibition. It is a fascinating and intimate selection of drawn works on paper that operate less through narrative or allegory, and more as a collection of indexical symbols, clues that point us to a potential reading but refuse to be too specific. These works feature, curiously, designs for flatpack structures and substrates, rendered with precision, amidst and in contrast to the lively, inky pools and expressive linework of myriad other forms (depicting, for example: a man holding a rifle, a zeppelin, a whale, a tick…) and periodic approximation of Ben-Day dots. One gets the sense from these pieces that this was a potentially limitless line of visual inquiry, that an artist could explore such a thematic rabbit hole for an entire career. Fortunately for us, Hoffie’s restlessness seems to dictate periodic gear changes.

The largest, most recent, and spectacular series is Clusterfkk. Comprising several large-scale pieces– each consisting of several sheets of watercolour and gouache on architect’s paper–the series hums and crackles with energy. Using no preparatory sketches or compositional schema, the work retains a lively, exploratory line that is further heightened by Hoffie’s colouring process. The wrinkling and warping of wet media on the velum-like paper also increases the seductive materiality of the surface. Hoffie is uncertain as to the long-term future of these works, given their unconventional creation. This signals the artist’s own anxieties around the future of the artist in a technologised world that seems hell-bent on stripping autonomy (and with it, the creative economy) from the people.

As an interesting counterpoint to this deep engagement with materiality, and interacting with what is certainly a source of tension and anxiety for many artists, Hoffie has used AI (ChatGPT to be exact) to write a brief ‘about the artist’ section in the exhibition’s accompanying publication. This has a curious value as a distancing device, for although the exhibition itself is often zoomed out to encompass the macro perspective of this global . . . well, mess we’re in, there are still plenty of ciphers in the work that could be taken as linked to the artist’s own life. While it would be vulgar and inaccurate to compare Hoffie’s situation with that, say, of an artist in Gaza or the Ukraine, her recent days have not been without their own challenges and heartaches. These are not documented or explored at any great length within the work, but small hints come through.

Much has been made of Hoffie drawing inspiration from Henry Darger’s epic drawings. The Vivian Girls, Darger’s recurring protagonists, appear sporadically through much of her recent work, updating their already complex war narrative for the 21st century. What is shocking, and more than a little disheartening, is how contemporary Darger’s outpourings still are today. Darger created more than 15,000 pages of drawings over six decades, documenting a war narrative of striking violence and brutality. Darger’s fantastical landscapes are as much an inspiration as their distribution of figures. There are also strong stylistic nods to artists like Daniel Richter and Neo Rauch, whose use of figures, particularly in regard to their situation in the composition, is crucial to their works’ overall sense of mise-en-scène. All three artists employ an idiosyncratic use of colour that is not entirely detached from the popular culture of their time, and Hoffie stays true to this also, refining the high contrast palette of recent work.

Rauch and Darger are also particularly notable in this context for their use of collaged imagery, which adds a fascinating level of visual disjuncture to their work; small shifts in perspective from figure to figure must be welded back into visual unity, an approach that must be consistently inconsistent. While Hoffie has not used collage to create her compositions, there is an element of collage still apparent through the unplanned and improvised nature of the Clusterfkk works (I refer to them collectively as Clusterfkkers), which are worked straight onto the surfaces, drawn from a variety of media and personal images. The large scale of the works and their media-derived referents conjures the work of Locust Jones, but where Jones’ approach is frantic and overwhelming, heightened by sections of media text, the intensity of Clusterfkk is grounded in its narrative and landscape. Here, landscape serves as both a compelling compositional ground upon which to work, and as an active participant in the events unfolding. These works belong to landscape as much as, if not more than, those struggling on its surface, once again underlining the basis for so much conflict, and the universality of this story.

The final body of work in the exhibition, Smoke and Mirrors (2016), is presented in the last space of the gallery, serving as a definitive coda to the themes of the exhibition. This series changes visual gears once more, this time the works are rendered in charcoal and ink on paper. Smoke and Mirrors operates in stark contrast to the intense colour and action of the rooms preceding it, here depicting more intimate, perhaps desperate, and melancholic human emotions. The most direct and easily the most stripped back compositions of the exhibition, these pieces are comprised of drawings of boats, densely populated with tiny figures, dwarfed by the inky oceans and skies that surround and engulf them. The ink and charcoal has settled in delicate, crystalline formations that evoke the source of so much of the global strife that people flee, oil. Sadly, these works reference a continuing issue that was by no means new during their execution in 2016 and will likely continue without a serious reconfiguration of the unsustainable economic systems that rely on ever-expanding growth. The title of the series, Smoke and Mirrors, alludes to the ways in which issues like the global refugee crisis are spun for political capital and scare mongering rather than humanitarian solutions, but the drawings themselves refocus this scapegoat rhetoric back to the human scale. The series is direct, emotive, and finalises the exhibition with a powerful punch to the guts.

Jonathan McBurnie is an artist and writer, and is the Director of Rockhampton Museum of Art. Jonathan lives and works on beautiful Darumbal country.