Back for its fifth year, the Brisbane Portrait Prize Finalists Exhibition opened at the Brisbane Powerhouse on the 28th of September. This year’s iteration is its biggest yet, with over 600 entries, nine separate awards, and over $88,000 of prize money on offer. The exhibition showcases the prize’s 84 finalists, 70 of whom are entered into the main competition, while the remaining 14 compete in the Next Gen category reserved for artists under the age of eighteen. In addition to the main award, the competition incorporates a number of special category prizes, including awards for digital portraiture, women artists, and experimental practice.

Unlike other portrait competitions, such as the Archibald Prize or the Portia Geach Memorial Award, the Brisbane Portrait Prize only accepts entries where both artist and sitter have a connection to Brisbane. The result is a locally grounded exhibition that sets out to celebrate the eclectic diversity of its subjects. Wandering the space, we’re treated to a wide range of subjects, styles, and media. Some of the portraits showcase notable Australians, while others focus on more ordinary individuals. Some present relatively straight-forward depictions of their subjects, while others foreground symbols and surrealism. Despite entries being restricted to two-dimensional works, capable of being hung for display, the exhibition nevertheless showcases a varied range of media, from oil paintings and traditional photographs to digital art and mixed media.

As I walked around the exhibit, however, it wasn’t long before a sense of uniformity began to emerge. Many of the portraits on display seemed to be organised around similar themes, notably the trials and joys of daily life: illness and grief, friendship and family. This quotidian angle situates the sitters within their communities, pictured at home or at work, often in their uniforms or holding the tools of their trades. This focus is reflected in the portraits’ accompanying descriptions, which focus extensively on biographical detail to the detriment of analysis or technique. In stark contrast to the archetype of the creative genius, the artists on display here are everyday Australians, navigating everyday lives. As well as being artists, they are also musicians, property agents, dentistry students, scientists. The moments in which they locate their sitters’ identities are so commonplace they become pedestrian: a man sprawled out on his couch with his dog, two tradies on smoko enjoying a sausage roll.

Is there value in demystifying the artist and their subject? Of course, but not so much that it veers into banality. Throughout the exhibit, scenes of domestic contentment and cheerful entrepreneurism preponderate, contributing to a somewhat tired narrative of Australian pluckiness, optimism, and opportunity. In this context, the exhibition’s more interrogative, psychological portraits feel like a palette cleanser. Ashlee Becks’s I See Right Through You (2023) is one such example. Becks depicts herself standing naked in front of the bathroom mirror, gazing searchingly into her reflection. Pink and cream shades underline her vulnerability, while the thick, disjointed brushstrokes create an impression of fracturing and multiplicity.

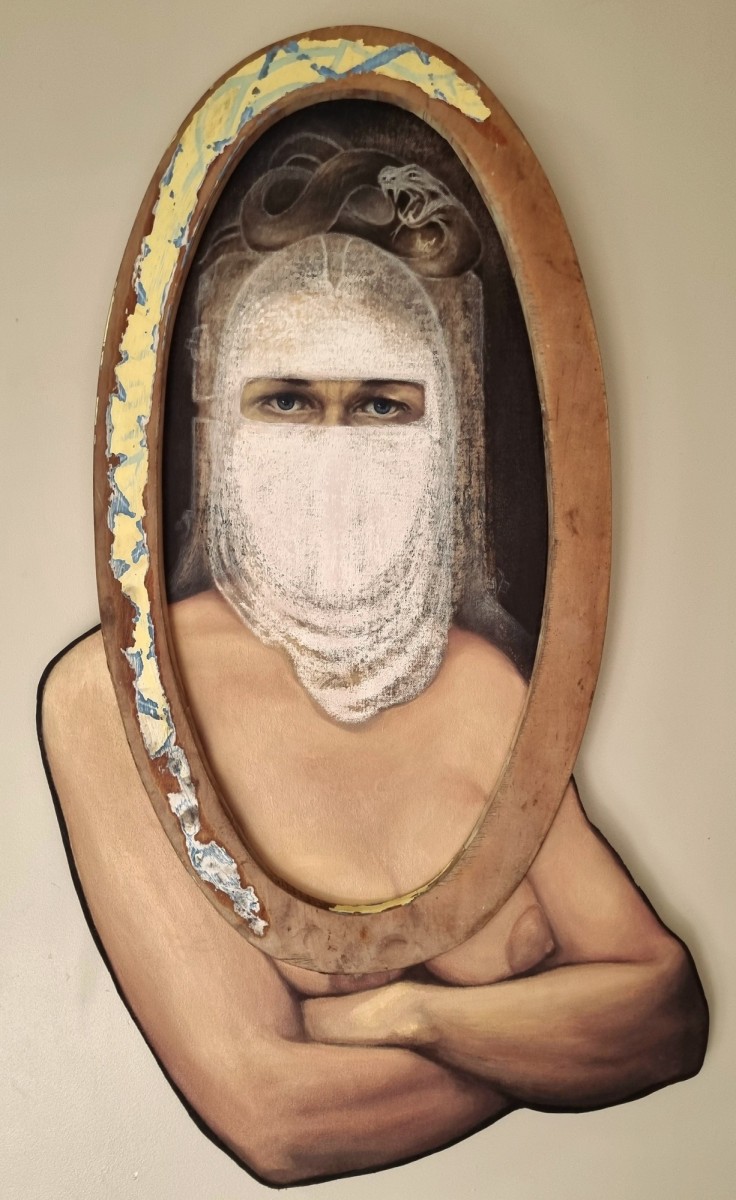

Meanwhile, Andrea Verheesen’s Changeling II (2023) raises questions of identity in a more confronting stance. Face covered with a diaphanous white veil resembling a niqab, Verheesen stares combatively out from the portrait’s oval wooden frame. She is off-centre, a snake curled on her head, her chest bare and her arms crossed. Tellingly, her body overspills expected boundaries, refusing to be contained within the reductive confines of the portrait-miniature frame.

Diversity is another emergent theme of the exhibition, with a number of portraits showcasing disabled, queer, and racially diverse sitters. Some of these portraits, like Luther Cora’s NOT MY QUEEN Sovereignty (2023) are overtly political. Others, like Paul de Zubicaray’s colourful portrait of Madeline Stuart, a diversity advocate and the world’s first supermodel with Down Syndrome and autism, are a clear celebration of disabled life and resilience. While this diversity is welcome, the arrangement of the exhibition places these pieces in an uneasy standoff against symbols of normativity and status quo. Portraits of CEOs, professional athletes, and city elites sit peaceful and unthreatened opposite the marginalised and disenfranchised. On one wall, Robert Mandeville’s striking self-portrait Robbie (2023) gazes hauntingly out of the frame, a reminder of the complex interiority so often denied to the disabled. On another, eight besuited men from the Brisbane Club gather around a table for wine tasting in Sangeeta Mahajan’s The Red Barons (2023). It’s enough to give you whiplash.

Ultimately, the Brisbane Portrait Prize Finalists Exhibition presents a pleasing, if anodyne, glimpse into the multifaceted and multicultural people who call Brisbane home. More interested in people than art, the exhibition succeeds in what it sets out to do: to “tell the stories of the diverse . . . and eclectic group of people who make up the character of our city”. Beneath this mission lies an unsettling, slightly forced cheerfulness; an insistence on celebrating Brisbane at the expense of serious challenge or criticism. The prize makes art and capitalism comfortable bed-fellows, and given the amount of money on offer, perhaps that isn’t surprising. Still, with four successful iterations under its belt—isn’t it time the Brisbane Portrait Prize stopped playing it safe?

Yen Radecki is a writer and editor currently based in Meanjin/Brisbane. Their short fiction has previously appeared in STORGY Magazine, Ibis House, and Forge Literary Magazine. Online, they can be found at @yenradecki.