“Three is the number through which we seemingly best view our world and perhaps, too, this exhibition.” So Adam Ford proposes in his accompanying essay to the third iteration of the King & Wood Mallesons’s First Nations Art Award [1]. Three is more than the number of times this biennial award has taken place; it also describes the ways in which First Nations art is all-encompassing and powerful. As Ford states:

Three bears the past, present, and future, which collapse into an ‘everywhen,’ an all at once or neither. Here, birth, life, and death are brought into coexistence. Artists today continue to draw from this immemorial phenomenon.

Throughout the continuing essay, Ford robustly positions the viewer for understanding the artistic expression of First Nations’ experiences, in an exhibition that brings together established and emerging artists working in a range of media and from urban, regional, and remote areas of the continent. Ford’s essay, a highlight of the exhibition, outlines that First Nations’ creative cultural expression is the very essence of this continent, not simply, as written in the award’s purpose, “[a] contribution made to Australian culture.”

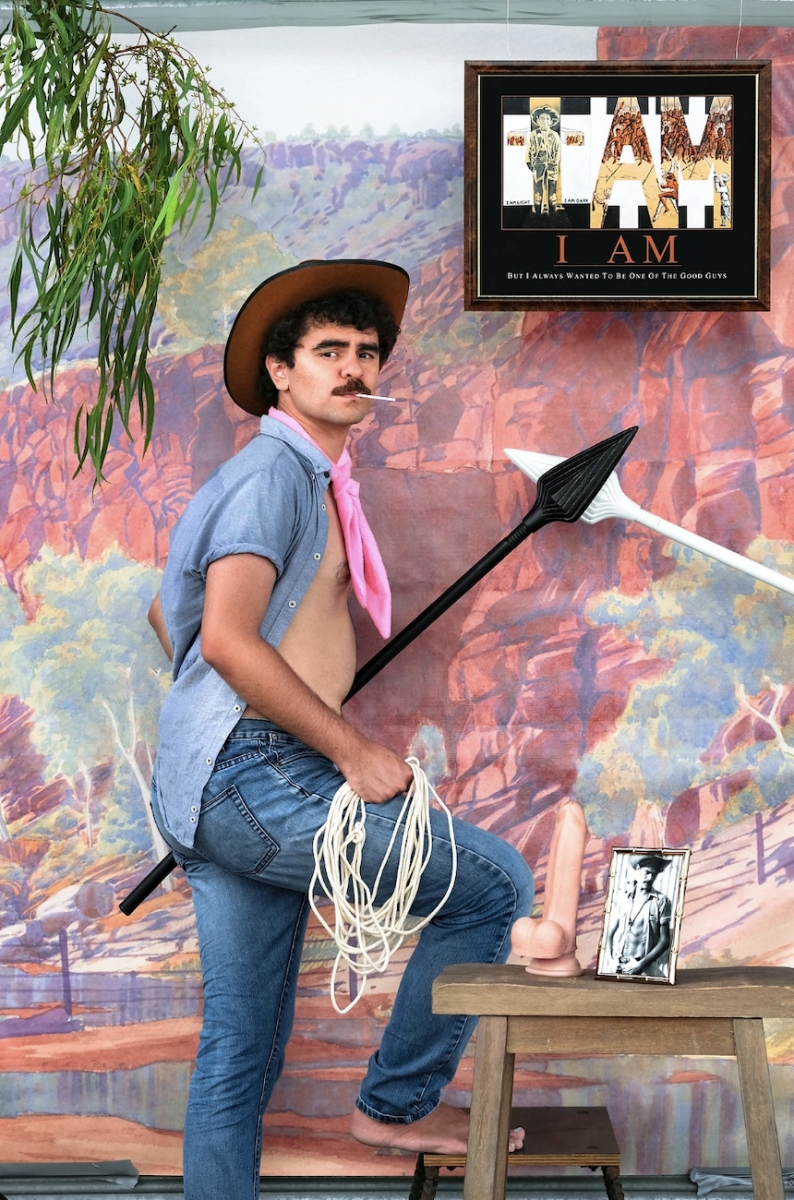

Displayed at Griffith University Art Museum, the award’s works were contrasted with each other via media and subject, showcasing First Nations’ identity as nuanced and expressed in many ways. Kaditj artist Cameron Ross’ The White Kangaroo (2023) was the first work in view. The small painting—consisting of intricate lines and a dotted kangaroo against a backdrop of red, white and black— is based on an experience of seeing the Kadatji Man, a spirit who presented as a pure white kangaroo to the artist. The vastness of Country is rendered on the two-dimensional surface in a constrained colour palette that both expands and contracts perspective. Next was Meriam Mer, Koa, and Kuku Yalanji artist Keemon Williams’ Self Portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the Macho Men) (2023), which was awarded the Queensland Local Artist Award. The photographic self-portrait heeds the artist’s converging identities as camp, queer and Indigenous. Williams’ work hangs across from established artist d Harding and their restrained exploration of similar themes in Gurri (Bidjara Blanket) (2023). Via a blanket held together with a rainbow belt, the artist eloquently expresses their queer and Indigenous identity. As they recount, “for a number of years now, this rainbow belt has held my bedding together, on my return to Bidjara and Garingbal and Ghungalu territories” [3]. Adjacent to each other, Williams’ and Harding’s works set up a strong vision of intersectional experiences of identity.

In the second room, the standout wall displayed a weaving and screenprint. Yolŋu master weaver Mary Dhapalany’s Twin Mat (2023) is a delicate woven tribute to her late brother, representing their intertwined spiritual connection. Kala Lagaw Ya artist Solomon Booth’s Mindfulness (2023) screenprint highlights the need for ocean sustainability. It depicts jellyfish amidst plastic bags, the latter confusing marine life and disrupting the sustainable food chains that have always been practised by First Nations people as part of caring for Country. Although using different media, Dhapalany and Booth’s works together highlight the deep connections of kinship and non-human relationships.

In the third room is the only video work and winner of the major award, Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman, and Gureng Gureng artist Richard Bell’s No Tin Shack (2022). The short film—based on an experience of growing up in Mitchell—is deeply personal and spells out the experience of many communities’ forced displacement, but also, resistance. Marri Ngarr artist Ryan Presley’s nearby pencil drawing Party Popper (Heart Stopper) (2022) also elicits resistance, albeit uneasy and violent. The drawing of a hand pulling on a taser trigger responds to the disproportionate brutality of police on Indigenous people. Presley’s drawing carries depth via this subject matter whilst also making a tongue-in-cheek visual motif as the taser throws confetti in the air. A mesmerising painting by Pintupi artist Adam Gibbs Tjapaljarri, Untitled (2022), contrasts with Bell and Presley. The work seems to move like the wind shifting sand. It depicts the sandhills of Country that form part of the Tingari cycle, encompassing the creation Dreamings, law, and Songlines of Country. Like Bell and Presley, the artist’s curving yet precise lines are imbued with rich storytelling .

The award gives this superb selection of artists and creative expressions of simultaneously ancient and contemporary culture a platform to display the ‘contribution’ of First Nations artists to so-called Australian culture as diverse, dynamic, ceaselessly sovereign, and always redefining the status quo.

Jocelyn Flynn is Notsi from Niu Ailan province, Papua Niugini with Anglo-Celtic lineages. She researches, writes, mediates and curates critically engaging projects.